SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Panay blackouts](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/panay-blackouts.jpg)

The challenges faced by the energy sector involving electricity outside the three main distribution franchise areas among the largest in Luzon and the two smaller ones based in Cebu and the last in Mindanao concern technical expertise and policy-making competence.

The lack of technical and experiential expertise and relevant track record, plus the continuous incompetence in policymaking, are at the core of the problem where island grids and off-grid networks are concerned. The Panay Island grid is a case in point.

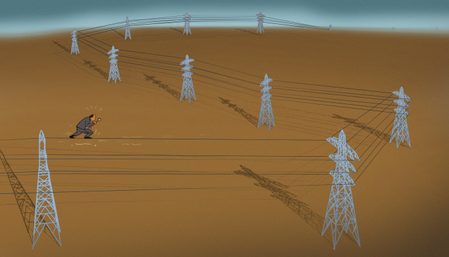

For the repeated outages, policy makers blame the transmission operator and yet the grid-wide blackouts originated at the distribution level. That by itself is telling. Transmission connects generating plants to distributors via high voltage towers. It is a wires business. Electricity supply is upstream generation.

Distribution is downstream. The inability to differentiate the responsibility of one from the other indicates a glaring gap in understanding grid management. Where power supply is sorely inadequate, the competent management of reserves to address scarce supplies become critical.

A blackout is a complete interruption of service in a grid.

The serial Panay blackouts have turned into an unfortunate polemic paragon. What should have been mere brownouts – pre-planned interruptions of service due to a baseload plant’s maintenance downtime where resultant outages are temporary; where brownouts are partial reductions of system voltages rolling area by area; and where these are managed by the electricity distributors – what should have been confined brownouts had worsened to total blackouts.

Let us be specific. Policy-wise, both market and ancillary reserves in the Visayas region are concentrated along the eastern Visayan corridor despite the worsening imbalance between supply and demand within the largest islands in the west where a dearth of adequate baseload capacity is aggravated by the presence of an inexperienced distribution utility (DU).

Stretching along both Visayan hemispheres, note how such mid-value chain incompetence extends upstream at the generation level where fuels are concerned. Especially notable is a policy reversal of the ban on expanding the use of toxic coal as a fuel for generating plants.

Recently, energy officials, despite the promises of Ferdinand R. Marcos, shifted from a moratorium on fossil fuels by unexpectedly approving the expansion of highly pollutive and toxic coal-fired plants to add to the supply in the east amid constant blackouts in the west. Why is the expansion of a coal-fired plant necessary to supply Cebu given the activation of the Mindanao – Visayas interconnection that supplies from surpluses?

That is the sort of policy reversal that aggravates reserve imbalances where one part of the Visayas is favored over others as the economics of the decision-making surrenders to other non-economic and possibly political albeit influential factors divorced from supply and demand.

From this overview, let us be even more specific and analyze the problem at ground level.

The repeated grid-wide power outages in Panay despite the recent take-over by a private conglomerate of traditional consumer owned and operated electric cooperatives (EC) and the switching-on of a long anticipated inter-island transmission system re-channeling surpluses to energy-deficit islands characterizes the continuous failures.

The avoidable albeit extensive blackouts in Panay at the start of the year were attributable to specific non-transmission-related causes.

In the bureaucracy immediately below these national government and regulatory levels, the competence of the privately owned and operated distribution utilities (DU) enters the picture. While the three major DUs linked by the National Grid Corporation of the Philippines (NGCP) are profitable propositions, the remote electricity cooperatives (EC) in rural areas are characteristically highly indebted and are notorious for operating below optimum bottom-line levels.

Given that a larger Panay power plant was already offline on a scheduled maintenance program – a predetermined condition – Panay’s distribution utility should have implemented load dropping protocols through its own substations. These controls are either automatically switched on or manually activated. The load dropping protocol strategically pre-selects large users with in-house generators and takes them offline so that the demand on limited supply is alleviated enough to prevent a tripping cascade that results in a grid-wide blackout.

In the case of the grid-wide January blackout in Panay, this did not happen.

Cabinet-level officials as well as non-technical pundits, PR operators and politicians of all colors and shades quickly blamed the cascading tripping of the Panay power plants on NGCP. What was a generation issue aggravated by the DU’s failure to parcel out limited power via load dropping protocols had been turned into a wires issue where it was not. Instead, ignoring the data on the ground, officials blamed NGCP for not providing adequate transmission capacity to transfer power surpluses, whether market or ancillary reserves, from the east to the west where Panay had the systemic baseload undersupply.

At the core of the constant haranguing is the critical difference in the scope of responsibilities where NGCP provides ancillary reserves that activate within seconds to seamlessly balance grid integrity on one hand and, at the generation end, the provision of market reserves that activate within hours to days that prevent outages, brownouts, and blackouts.

What folly or shortcomings that lead to often predatory pricing and ridiculously astronomical power rates that appear on a privately owned and operated DU’s billing statement however do not exonerate the Department of Energy (DOE), or its regulatory arm, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC). There is a short, continuous, and uncut umbilical cord between the DOE, the ERC, and the private sector entities responsible for, if not complicit, in astronomical rural electricity rates amid power outages now repeatedly and continuously experienced in Panay.

While criticism focused on NGCP’s dividend policies from retained earnings accumulated over the years might be valid, its capital structure and technical partner open to sovereignty debates and the continuing conflicts of interest between its majority stakeholder and the DOE bureaucracy open to controversy, the question of the Panay blackouts is a totally different matter.

Recently, the Panay grid was again victimized by four hours of blackouts. Again, officials and politicians blamed NGCP even after NGCP had on January 26, 2024, energized its 450-megawatt Mindanao-Visayas submarine cable that transmits Mindanao’s surplus to the Visayas and thus should alleviate any undersupply in Cebu, allowing reserves at that end to be shared via the Cebu-Negros-Panay cable enough to forestall Panay blackouts.

These blame games reflect gross ignorance of the nature of reserves at the policy level where the supply inadequacies and reserve imbalances of the Visayas Grid are due to the lack of resource adequacy assessments which is the responsibility of the DOE.

In its place are blind transmission transfers that place the burden on NGCP. This reflects the failure to understand the difference between generation and transmission where a resource adequacy assessment considers both. One cannot cover for the shortcomings of the other as the undersupply of any one of the two distinct resources results in the inadequacy repeatedly plaguing Panay. – Rappler.com

Dean de la Paz is a former investment banker and managing director of a New Jersey-based power company operating in the Philippines. He is the chairman of the board of a renewable energy company and is a retired Business Policy, Finance, and Mathematics professor. He collects Godzilla figures and antique tin robots.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Panay pretexts and power plays](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/panay-power-blackout-january-17-2024.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[ANALYSIS] Why do we pay higher power rates when we have power outages?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/tl-higher-power-rates-higher-power-outages.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=401px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

As DEAN DE LA PAZ stated, “These blame games reflect gross ignorance of the nature of reserves at the policy level … are due to the lack of resource adequacy assessments, which is the responsibility of the DOE.” So, the DOE must do the said resource adequacy assessments.