SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Decommissioning BNPP, and storing the nuclear dragon’s radioactive manure](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/11/Screen-Shot-2021-11-09-at-4.02.33-PM.png)

The following is the 18th in a series of excerpts from Kelvin Rodolfo’s ongoing book project “Tilting at the Monster of Morong: Forays Against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant and Global Nuclear Energy.“

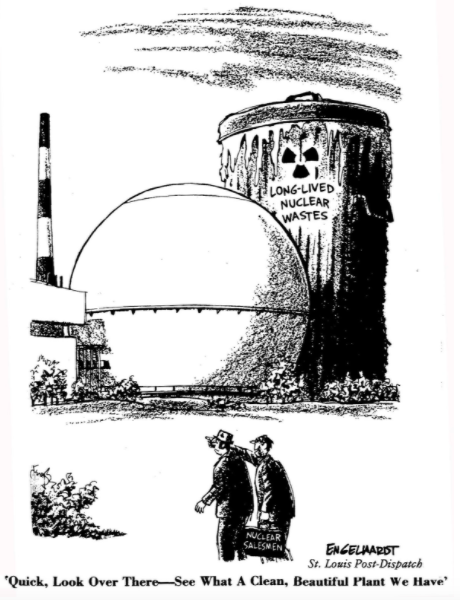

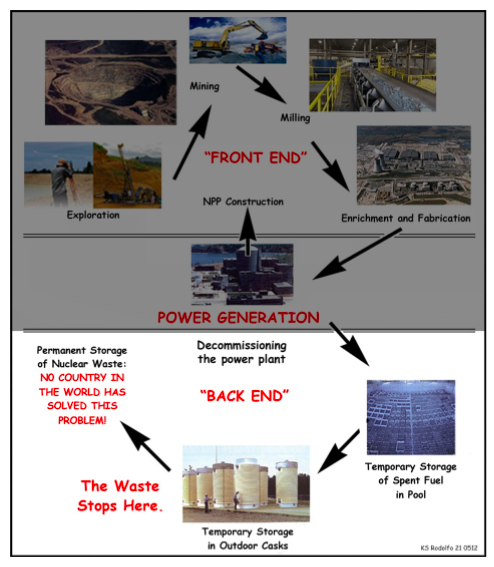

Nuclear power pushers rarely mention the huge “back-end” costs of nuclear energy. But if the Philippine government commits to using nuclear energy, it also commits us to decommissioning the reactors properly when the time comes. And we must immediately begin safely storing and disposing of its waste.

The certainly enormous, open-ended amounts of energy and treasure involved are called an irrevocable “nuclear debt” or “nuclear mortgage” by Dutch scientist Jan Storm van Leeuwen. This is because, if done properly, the “back end” almost certainly costs more than the front end. But industries, after reaping their profits, don’t want to spend money and effort on repairing the environment and protecting the affected people. Just look at the devastated landscape around any abandoned mine in the Philippines.

Decommissioning BNPP

BNPP has bad karma. It cost $2.9 billion to build, including $640 million to finance the debt, but has produced not a single watt-second of electricity.

Yankee Nuclear Power Station in Massachusetts, a 620-megawatt plant like BNPP, had bad karma too. It cost $39 million to build from 1958 to 1960. After operating 32 years until 1992, it took 15 years to decommission – five times longer than it took to build!

Decommissioning also cost $608 million -– 16.6 times more than to construct. And the spent-fuel facility still costs $8 million annually to guard against terrorists or accidental spills into the river that used to provide its cooling water.

Yankee Nuclear Power Station informs us that if BNPP is ever activated we will pay a very hefty price for decommissioning it properly after its 40-year life. Customers would pay these costs. Mark Cojuangco’s BNPP bill proposes that Filipinos would pay a $0.002 tax for every kilowatt-hour generated, not just by BNPP, to be accumulated against decommissioning costs.

But long before that, just as soon as BNPP starts working, it must handle, contain, and guard its waste.

Storing BNPP’s radioactive nuclear waste

Cojuangco would also charge every Filipino electricity customer another $0.001 to pay for handling BNPP’s nuclear waste. Those fees would not nearly be enough.

Pressurized water reactors contain 80 to 100 tons of uranium in little uranium oxide pellets packed inside zirconium tubes as big around as your thumb and about 4 meters long, bundled into fuel assemblies. Reactors hold 150 to 250 fuel assemblies at a time.

After a fuel assembly has been used for four to six years, only about 20% of its uranium remains. It is still very radioactive, but not enough to use in the reactor.

And so a fourth to a third of the assemblies are replaced every 12 to 18 months. To absorb their radiation and heat, they are stored upright under at least 7 meters of water in “spent-fuel” pools, typically 40-meter cubes thickly lined with steel and concrete.

We will see in a later foray that spent-fuel pools can be deadly if disaster hits the nuclear plant, as happened in 2011 at Fukushima in Japan.

After five years or so in the pool, the used fuel is cool enough to be transferred outside, into casks of reinforced concrete. There, the heat emitted by their own decay drives natural convective air flow that continues to cool them.

Outdoor casks are meant to be only temporary, awaiting permanent storage where they would be out of harm’s way forever. But as yet, no country in the world has solved that problem.

The casks are safer than pools, but natural disasters or terrorists can rupture them and widely disperse their intensely radioactive contents. Protecting them will cost energy and money far into the future.

Nuclear advocates used to claim that the spent fuel could be processed to recover the remaining 20% of U235, as well as the plutonium created in the reactor, to use as fuel. That would reduce the quantities to store. But recycling probably never will happen, for reasons we explored earlier in Foray 12.

And so, because the spent fuel can neither be recycled nor permanently stored, the back end is blocked and backing up – totally constipated, so to speak. All over the world, spent fuel assemblies continue to accumulate at NPPs. About 75% of them are dangerously crowded together in spent-fuel pools, which now hold several times more assemblies than they were originally designed to hold, vulnerable to a catastrophic fire.

Final disposal is an intractable problem with unimaginable cost

Spent fuel accumulates in pools and outdoor casks all over the world, awaiting safe and permanent storage. But no country knows how to do this, a fact that nuclear propagandists minimize or dismiss.

In 1978, the US began to study 10 possible sites to use for storing its nuclear waste deep underground. Yucca Mountain in Nevada was selected in 1987. In 2008 the US Department of Energy estimated that the repository there would require up to $96 billion to complete.

But in 2009, after $13.5 billion had been spent on the project, it was canceled because of serious geological safety concerns, and because the public strongly opposed it. No alternative site has yet been identified.

In 2019, the US had accumulated 90,000 tons of waste at 85 sites in 35 states. This is expected to increase to about 140,000 tons over the next several decades. US taxpayers continue to pay $800 million every year to maintain and guard the waste, while awaiting the final repository that may never be.

If and when the problem of permanent storage is ever solved, we can only speculate about how much it would cost. But we cannot ignore or minimize the problem, as the international nuclear lobby and the Philippine government do.

Implications for BNPP

Carlo Arcilla, Director of the Philippine Nuclear Research Institute, has made light of the problem of permanent storage: “Give me one island out of our 7,000 and I can find ways to store nuclear waste safely.” His model is the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in underground salt deposits near Carlsbad, New Mexico. But that plant accepts only clothing, equipment, tools, sludges, and soils contaminated during weapons manufacture. Power plant nuclear waste is too radioactive, emits too much heat, and includes too much liquid.

Arcilla once said nuclear waste can be injected in deep drill holes in his selected waste-island. He may have been following the lead of the US Department of Energy, which announced in December 2016 that it was exploring the possibility of conducting deep borehole field tests in two states.

Unfortunately for Arcilla, the program was permanently terminated in May 2017.

In May 2021 the Philippine Congress took the first formal steps to establish a Philippine Atomic Regulatory Commission. The Secretary of Science and Technology concurred: “There needs to be a separate agency” apart from Arcilla’s Philippine Nuclear Research Institute.

Is this a good thing? Probably not. Clearly, Congress seems to assume that nuclear power is a given for the future, without fully evaluating all the implications that these forays explore.

Our next foray will summarize the true costs in global warming of all the carbon dioxide produced by the entire nuclear fuel cycle. – Rappler.com

Keep posted on Rappler for the next installment of Rodolfo’s series.

Born in Manila and educated at UP Diliman and the University of Southern California, Dr. Kelvin Rodolfo taught geology and environmental science at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1966. He specialized in Philippine natural hazards since the 1980s.

Previous pieces from Tilting at the Monster of Morong:

- [OPINION] Tilting at the Monster of Morong

- [OPINION] Mount Natib and her sisters

- [OPINION] Sear, kill, obliterate: On pyroclastic flows and surges

- [OPINION] Beneath the waters of Subic Bay an old pyroclastic-flow deposit, and many faults

- [OPINION] Propaganda about faulting, earthquakes, and the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Discovering the Lubao Fault

- [OPINION] The Lubao Fault at BNPP, and the volcanic threats there

- [OPINION] How Natib volcano and her 2 sisters came to be

- [OPINION] More BNPP threats: A Manila Trench megathrust earthquake and its tsunamis

- [OPINION] Shoddy, shoddy, shoddy: How they built the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Where, oh where, would BNPP’s fuel come from?

- [OPINION] ‘Megatons to Megawatts’: Prices and true costs of nuclear energy

- [OPINION] Uranium enrichment for energy leads to enrichment for weapons

- [OPINION] Introducing the nuclear fuel cycle

- [OPINION] On uranium mining and milling

- [OPINION] Enriching and fabricating BNPP’s uranium fuel

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.