SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

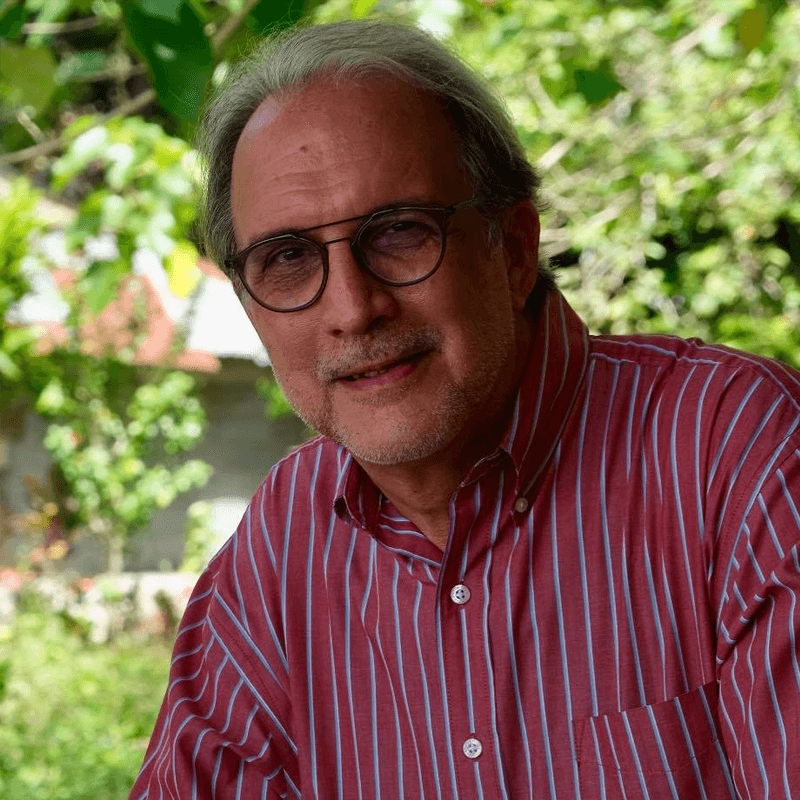

It is uncommon for a non-Asian to win the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award, a prize that is usually given to Asian individuals and organizations who achieve excellence in their respective fields. But in 2021, the foundation awarded Steven Muncy, an American humanitarian.

Muncy is no stranger to the Philippines and Southeast Asia. After all, he has worked in Southeast Asian countries since 1980 and has established a Philippine-based international nongovernmental organization called the Community and Family Services International (CFSI).

CFSI is a humanitarian organization committed to “the lives, well-being, and dignity of people uprooted by persecution, armed conflict, disasters, and other exceptionally difficult circumstances.”

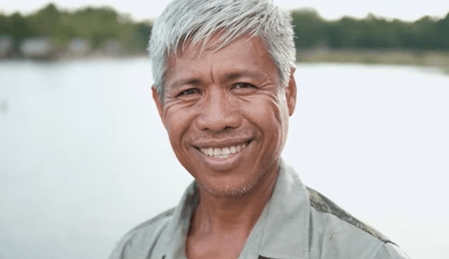

Muncy is one of the five awardees of the Ramon Magsaysay Awards Foundation (RMAF) in 2021, alongside Filipino fisherman Roberto Ballon, Bangladeshi scientist Firdausi Qadri, Pakistani visionary Muhammad Amjad Saqib, and Indonesian production house WatchDoc.

Becoming a social worker

Muncy came to the Philippines as part of the Journeymen program in 1980, when he was just 23 years old. He was a working student when he saw reports of people fleeing Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia.

The three countries were in the middle of the Indochina refugee crisis at the time. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) said that over 3 million people were displaced and fled their homes due to the crisis.

“I had never been outside the US. I didn’t know much about the world outside the US. But, for some reason, the plight of the Cambodian people, in particular, grabbed hold of me. I came in response to the refugee situation that was impacting the region in a very big way,” Muncy said during a virtual roundtable interview with reporters on September 10.

Muncy described the Journeymen program as “somewhat like the Peace Corps,” where young individuals are given the chance to work abroad for two years in a variety of roles, including ministry-related work, social agriculture, and teaching.

The program gives its delegates free accommodation, roundtrip airfare, and a “very, very small stipend,” said Muncy. When he was selected, he was given a choice whether to go to Thailand or the Philippines.

“What attracted me to the Philippines was the fact that, at that point in time, the Philippines, which was offering refuge for refugees from countries like Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam, was at the same time persecuting its own people. There was Martial Law. There were people who fled the Philippines because they felt like they could not stay safely in this country,” Muncy said.

The young social work student found that dilemma so interesting that he decided to apply for an assignment to the Philippines. It was 1980.

After a competitive selection process, Muncy was sent to the Philippine Refugee Processing Center in Morong, Bataan, where he was tasked to teach electricity to the refugees to help them with their livelihood. Although the young social worker knew nothing about the task given to him, he stayed and eventually learned more about the other needs of the refugees.

“Very shortly, it became clear to me that there were many refugees in that camp who needed the kind of services for which I was trained: counseling, social work, problem-solving, supporting families in difficult times,” Muncy said.

About a year later, he decided to leave the Journeymen program to start CFSI to address the growing psychosocial needs of the refugees in the camp.

Establishing CFSI

Leaving the Journeymen program meant Muncy had to forgo his benefits, including the stipend and the free airfare back to his home country.

“I’ll tell you very frankly, I had no money. Food became an issue very quickly,” Muncy admitted. He said CFSI would not be the way it is today if not for retired general Gaudencio Tobias, who supported his needs as he was starting CFSI.

Tobias took care of Muncy’s meals. But because Muncy did not want to burden the general, he usually opted to eat packs of Chippy, a Filipino brand of corn chips, and bottles of Coke.

Other volunteers helped Muncy establish CFSI. Some of them were spouses of full-time employees in the camp who were willing to give their time to the organization, while others were social workers. Muncy said most of them worked for free.

However, Muncy soon realized that in order to really do something, the organization had to have some cash. The first donation came in 1981 from a group of expatriate workers whom Muncy did not even know at the time. The group gave CFSI $600.

“The first year, for myself, I had no income. We really had no money. So we had that small donation, and we wrote proposals at night,” Muncy said during a one-on-one interview with Rappler on September 23.

Money started coming into the foundation in April 1982, which allowing them to expand their services and staff.

The organization owes it to the Norwegian government, through a Norwegian humanitarian coordinator, who asked to receive a proposal from CFSI in 1981. The proposal was approved and the funding was coursed through the UNHCR. CFSI and the UNHCR have been partners ever since.

Today, CFSI is composed of about 400 people and works in three countries: the Philippines, Myanmar, and Vietnam. It has also assisted refugees in 48 countries and territories over the years.

“It’s done more than we ever expected. Most of us thought that the refugees coming into the Philippines…would only do so for five, six, seven, eight years. So when we established the organization, believe it or not, we said in the incorporation papers that it would have a life span of 10 years. But the refugees continued to come…. I think, maybe nine years into our work, we were then asked to expand to the other countries in the region,” Muncy told Rappler.

Psychosocial services and education

When CFSI started, it focused on psychosocial services, such as counseling and mental health support. Muncy decided to address this need after he encountered many women refugees in the camp in Bataan who were attacked and raped by sea pirates.

“Doing this day in and day out, it became clear to me that we needed psychosocial and mental health services. Back then, that was rather unusual and not worthy of donor support,” Muncy said.

The organization provided basic counseling, needs assessment, all the way up to psychiatric care. As they were able to develop the program, they were able to bring in psychiatrists from Manila. They also got support from the Norwegian Psychiatric Association.

As the organization grew, it started expanding its services to livelihood and water sanitation. But perhaps a distinctive work that CFSI is doing now is providing education not only to refugees but also to social workers in conflict-affected areas.

CFSI developed the Social Work Education Project, wherein they bring the master’s program to social workers who can’t afford to leave the conflict-affected areas they’re in. CFSI has partnered with different institutions to make this happen.

The program has helped more than 300 individuals across the region to get advanced university degrees in social work. In Cotabato City alone, Muncy said, they were able to graduate 100 people at the master’s degree level.

In addition, CFSI invests its time and energy in providing education to children, out-of-school youth, and illiterate refugees.

Filipino at heart

Muncy, now 64 years old, has been in the Philippines for more than half his life. Much of his life has been devoted to humanitarian work in the Philippines and Southeast Asia, but all of this would not have been possible had it not been for his early life in the US.

“I really don’t know when I first encountered a social worker. I come from a very humble family and I had not planned to go to university. It was something beyond us,” Muncy told Rappler.

He was able to go to college through a scholarship, and applied for an accountancy degree. In his first year, however, he took a class on social problems, and everything has changed since then.

“I knew right then and there that that’s what I wanted to do. Why, I don’t know. But something just resonated with me and I’ve never looked back since then,” Muncy said.

Muncy and CFSI have come a long way. The American humanitarian has been in the Philippines for over 40 years now, but he has no plans of slowing down.

“This is a good place for me. I would hope, if the powers would allow me to remain in the country, I’d be happy to do that,” Muncy said.

Muncy also shared that he plans to use his Ramon Magsaysay Award to raise more funds for CFSI.

“I’m going to be very candid with all of you. I hope to use the Ramon Magsaysay award as a platform to raise $10 million by the end of the 40th anniversary year of CFSI. I’d like to see $10 million or P500 million coming into CFSI that would allow us to do things,” Muncy said.

CFSI has been commemorating its 40th year since June 1, and its celebration will end on May 31, 2022.

The money that Muncy hopes to raise for CFSI will be used primarily for two things. One is to expand CFSI’s response to humanitarian situations in the Philippines and Myanmar. Myanmar has been in turmoil since the military seized power on February 1.

The other is to train more people at the master’s degree level in social work, which would entail working with schools of social work in the region, to help them develop a curriculum that is focused on displacement, humanitarian action, and peace-building. Muncy also hopes it could help them provide scholarships so that people can finish degrees in social work.

I think the biggest challenge is helping people understand why they should help.

Steven Muncy

“It’s very easy to think of the ‘other’ as out there and not my responsibility. My point of view is we all belong to the human family, so if one is suffering, we have a responsibility to extend help,” Muncy said.

For this thankless job, the RMAF said it recognizes Muncy’s work in helping displaced refugees of Southeast Asia rebuild their lives.

“The RMAF board of trustees recognizes his unshakable belief in the goodness of man that inspires in others the desire to serve; his life-long dedication to humanitarian work, refugee assistance, and peacebuilding; and his unstinting pursuit of dignity, peace, and harmony for people in exceptionally difficult circumstances in Asia,” the RMAF said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Strengthen civilian agencies, limit military involvement in disaster response](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/06/tl-military-calamityresponse.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.