SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

WASHINGTON, DC, USA — There is a Filipina behind the 2024 Sundance Film Festival, whose work is crucial to the event, despite rarely receiving the spotlight. Irene Soriano, a seasoned veteran in the world of film programming, had the honor of being part of the selection team that netted a wide variety of short films for this year’s festival. Remarkably, many of the films came from Filipino filmmakers, making the occasion even more special.

“I think people think it’s very glamorous, but programming work, you know, we had 12,000 short film submissions,” she shared with me in a Zoom interview at Los Angeles, having just returned from Utah, the home of Sundance. “Sundance is like the apex of American film festivals, and to be able to be in the center of choosing what’s next in independent filmmaking is an honor.”

A lover of film and music since her college days, pursuing the literary arts at the Loyola Marymount University at Los Angeles would be her portal to film programming: “I wanted to curate music videos by Filipino directors because nobody was paying attention to Filipino cinema in Los Angeles. So, what do you do if the festivals are not paying attention? Do it yourself. That’s always been my motto, DIY, do it yourself until everybody catches up.”

Since 1999, Soriano has been doing just that. Her groundbreaking start as the first “Project Involve” Fellow in Film Programming back in 2003 thrust her to the forefront of curating Asian American cinema and eventually becoming a mentor herself.

Her impressive curatorial efforts have also enriched organizations such as the Echo Park Film Center, the Filipino American National Historical Society, and the Festival of Philippine Arts & Culture. Moreover, her recognized expertise has led to her involvement in screening committees for esteemed film festivals, including the Los Angeles Film Festival, Outfest Film Festival, Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival, and now, the Sundance Film Festival.

During a special interview, Irene and I explored the behind-the-scenes realities of film festivals, the increasing acknowledgment of Filipino filmmakers across the globe, and the importance of fostering a supportive environment that seeks to normalize filmmaking and film programming — especially when faced with our pragmatic and ever-skeptical Filipino parents.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

How is it like telling people they got into Sundance, especially Filipino filmmakers?

You know, it’s definitely the highlight of doing this work. When we make the call, it’s like a reward for all that hard work because you see the raw happiness and excitement and glee from the filmmakers that they got in. Some cry, some go quiet. Some challenge you by saying, “Is this a prank?”

I was talking to another filmmaker who said, I think it was Whammy, and Alemberg [Ang], his producer, I told him, “Yeah, yeah. Look me up on Google.” (Laughter) I also had the privilege of calling Maria Estela Paiso last year, and the only reason why that’s memorable to me is I absolutely love that short film [it’s raining frogs outside], so to be able to call and let her know was really exciting for me.

I saw that as early as 1999. You’ve been programming for independent film, so tell me a bit about yourself and how did your journey towards film programming start?

When I entered college, I really loved music and I loved film, so I’ve always loved that combination. And for a long time, you know, when I was in high school, I thought I was going to be one of two things. Either I was going to be a manager for a band, or I was going to be a music video director.

Unfortunately, I was under the pressure of parents’ expectations. So, film school was not a reality in my head. And I fell into the pressure and entered this business because my dad was a businessman. And you know, an artist goes into business school, of course, I failed all the math classes. My plan was to transfer into the film school but my GPA ended up being lower than the required minimum.

So, I majored in creative writing poetry and stayed the course. And then I graduated, and I organized literary readings for Filipino American writers, Asian American writers. I don’t come from a rich family with big resources, so it’s not like I could leave everything and start doing film programmer roles, right? It doesn’t pay well even now. So, I had to have a job. I worked at UCLA as an office manager for Asian American Studies, but I made sure that after work and on the weekends, I was always doing something art-related.

I did an event for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month and picked Asian American documentaries. When the event happened, these students came out and I would hear them say, “My God, I’ve never seen us onscreen.” After hearing that, it clicked for me that that’s what I want to be doing.

I think it’s very powerful to be able to move the needle and have your faces and stories seen onscreen. So, who does that? It’s the programmers. It’s programmers who pick these films that get shown in festivals.

What has been your guiding principle when it comes to programming?

My guiding principle has always been to find the best directors with the best stories and move those narratives forward. Of course, I always have an eye for diversity. I mean, this is kind of standard to say, but for a long time in the independent scene, opportunities for filmmakers of color were very limited. And so, this is a period where, not that it’s hip, but it’s the world realizing that diversity makes any kind of discipline stronger.

My programming also leans towards more films that have something to say about the world, about social justice-themed films. It’s not to say that they’re all documentaries that talk about an issue, but they can be a narrative film that really looks at an issue and reveals certain truths about society.

It’s seductive to look at Whammy’s film as being about gay internet sex, but look at the interview, it’s also a very anti-Marcos piece. That’s what I love seeing, films that carry these big and small ideas in a way where somebody watches and is entertained and has so much fun, and then later they’re like, yeah, let’s start thinking about it. That’s what happens to me. I will watch a film and five years later down the line, I’ll say, “I didn’t even think of it that way.”

That’s the power of cinema, and that’s what I want to happen with somebody watching something that I curated. It doesn’t end after you leave.

So are there any standout films that you’d like to point out across the vast history of your career?

I’ve already said Maria Estela Paiso’s it’s raining frogs outside. It’s really amazing. Never seen anything like it. So, she will always be up in my top five across the board. I program here in LA too and I really like Ara Chawdhury’s Ms. Bulalacao. I think that has been underrated. I have a soft spot for women and non-binary filmmakers. Also Stephen Lee’s Manila is Full of Men Named Boy. It’s a black and white [short film], and Bembol Roco’s in it.

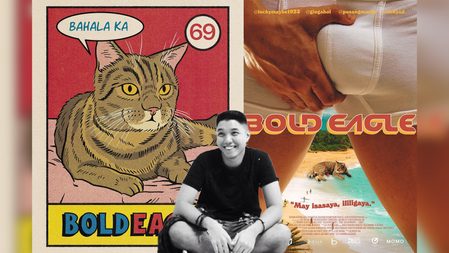

The selection of films this year for Sundance is amazing. You know, I love the fact that these are topics that are not discussed on the dinner table, they’re taboo. Sex addiction, gore, and blood. I mean, Whammy’s [Bold Eagle] is crazy. Crazy.

Aside from the ones I’ve already mentioned, some other films I really loved and would want to program if given the chance are: JT Trinidad’s the river that never ends, Sam Manacsa’s Cross My Heart & Hope To Die, Rafael Manuel’s Filipiñana, Xenia Glen’s Alo, Lav Diaz’s Ang Hupa (The Halt), Valerie Castillo Martinez’s Death of Nintendo, and Gabriela Serrano’s Dikit.

What are some of the most interesting trends in representation that you’ve observed over the two decades you’ve worked?

Filipino filmmakers are showing up in droves in Europe, in America, in Asia, and they’re being screened, and they’re being awarded. Here on the US side, I’m amazed at how we’re showing up at Sundance two years in a row. We won the Grand Jury Prize for short films back-to-back. And the audience too, they’re showing up and they’re considering independent films. If we do not have an audience, we do not have a screening or a festival or anything.

We [Filipino American film community] were talking about it, trying to figure out what’s going on. Like, why do we suddenly see a lot of Filipino filmmakers showing up in these different places. And I know for a fact, here in the US, that a lot more of them are coming out of film school. I did this panel at last year’s Sundance and I said, “What do your parents think about you going into filmmaking?”

And the surprising thing for me is that their parents were supportive of them. And so, a lot of these younger filmmakers are finally creating in a space where they are supported. And when you do that, you can only create good work. And when you create good work, it gets recognized, and you get shown.

And then the last trend that I see is the efforts of Southeast Asian filmmakers coming together and saying, “Hey, we’re from a certain region and we’re going to band together to let international festivals and bodies decide certain things that you need to pay attention to in our region.”

We’re very different from Korean cinema. We’re very different from Japanese or Chinese cinema. There are a number of us coming together, like the Vietnamese-American cinema workers, the Thai, Indonesian, Cambodian workers, we’re all coming together and meeting and trying to see how we forward our work as Southeast Asian cinema workers or filmmakers.

I want to ask what are some of the factors right now that still hinder the full potential of representation being realized in industry?

I always feel like access is an issue. I was talking to Ara Chawdhury, the filmmaker from the Philippines, who now lives here in the US. I told her, “You know, I wish more Filipino filmmakers would submit to Sundance.”

And she said, “Irene, that sounds really easy, but it costs money to apply.” And if you don’t have the resources, if you’ve just spent however many dollars and pesos getting your film made, $45 to $85, is a lot for a filmmaker in the Philippines holding on to their money, right?

So I think access like that is something to look at. We want to raise money so that we can invite filmmakers that need to be exposed to Sundance. They need to meet people and talk to other filmmakers. It’s why it’s important to raise funds so that we can sponsor and cover their housing.

I think one of the other challenges is just an awareness of who Filipinos are. For the most part, here in the US, there is the Asian/Pacific Islander (API) umbrella. But when you look at certain things or events or offerings regarding entertainment or filmmaking, the East Asian part of that umbrella is way ahead. The PI of API, we’re behind.

So, when a festival programs and they want to, let’s say, address the API representation, who do they pick, right? Are they aware of the Southeast Asian region? Are they aware of the PI or Pasifika filmmakers? Maybe they have contacts within the more East Asian groups. So how do we create a situation where we can get in there and say, look, if you really want a more expansive sort of representation of API, we’re here and we’ll provide resources or give you names and films.

Additionally, I had just met with a group of visual arts artists who wanted to put together a group here in LA to promote their works. And one of the conversations we had is that a lot of them, when they go to their parents and say, I want to be an artist, the parents panic. They’re like, you’re going to be poor for the rest of your life.

I said earlier that luckily Kayla [Abuda Galang], Jarreau [Carrillo], and other Filipino filmmakers had very supportive parents. How about all the other youth that want to go into this? And they’re told, you know what, it’s probably better if you become a nurse, a doctor or an accountant or something that will make money.

I think a larger conversation has to be had about this. Parents will be parents, but how do we arm our youth to be able to talk about cinema work as something they can enter and thrive in? I think that’s a challenge that needs to be addressed. And for aspiring Filipino artists, we have groups like Cinema Sala and FilAm Creatives.

It’s about what can we do so that when we do outreach in the community, it’s not just go watch our films or take this class, it’s about how do we create appreciation around cinema, watching, creating, and getting audiences in, but also promoting the idea that if we wanted to go into cinema work that it’s going to be okay.

What sort of advice would you give to aspiring film programmers and where do they start?

One of the things I always say is talk to a film programmer, because like I said earlier, it seems really glamorous, but it still takes work. Find out what a film programmer’s day looks like or what a festival season looks like for them. Figure out if that sounds like something they want to do right before investing any kind of money or time and resources. So that’s one thing, you talk to some programmer, interview them, find out what it’s like.

And then second, if you find that you’re really interested, then I’m hoping that you are watching a lot of films. You know that cinema watching is part of your reality and you’re reading up on the internet what is there for you. It wasn’t the case for me in 2000 that you can now find out basically what’s going on in independent filmmaking from all over the world at your fingertips.

Third, volunteer for your local film festival. And if you’re more of an entrepreneurial spirit, create your own screening or film festival. I’m a big proponent of DIY. If the festivals that you’re in or the film groups around you are not showing what you want to be seen, you do it. Hit up the organizations who have resources. My hope is that if you do not have programming fellowships available in your area, work towards having one created.

Volunteer for film festivals but don’t be a volunteer forever. Always make sure you’re paying attention to see if there are any opportunities to move forward in your work. There are people all around the world who can help you. I will even help you if you’re in a small town somewhere and you need to set up a film programing program.

One of the programs I would love to develop is a script-to-screen fellowship that provides resources, production, and exhibition opportunities for our promising filmmakers in the diaspora. If there are resourced people truly invested in growing our filmmaking legacy and finding new, fresh voices, I want to meet you. Let’s bridge the diaspora! The pipeline can no longer just be the US and the Philippines. We are all over the world! Our stories are truly global.

Let’s say I’m in the shoes of a filmmaker wanting to go to festivals. What should they know about programming?

Always make your film. Do not go towards what festivals seem to be accepting. Do what you do, do it well and it’ll shine, and somebody will see it. I’m not saying every short film that’s submitted will be accepted, but you have a better chance of being accepted if it is your vision and the vision is strong. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Only IN Hollywood] ‘Kinds of Kindness’ cast, Lanthimos on their ‘bizarre, special’ film](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/KindsofKindness-Emma-Stone-Yorgos-Lanthimos-and-Jesse-Plemons-at-the-New-York-premiere-of-Kinds-of-Kindness-Searchlight-Pictures11.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=238px%2C0px%2C853px%2C853px)

![[Only IN Hollywood] Producer Alemberg Ang reveals details on Isabel Sandoval’s ‘Moonglow,’ other projects](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/AlembergAng-Alemberg-Ang-Isabel-Sandoval-and-Arjo-Atayde-on-set-of-their-Moonglow-set-in-the-60s-and-70s.-Contributed-Photo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Only IN Hollywood] Kevin Costner’s big financial gamble to make not one but four ‘Horizon’ films](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/kevin-costner-standing-ovation.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=187px%2C0px%2C853px%2C853px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.