SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

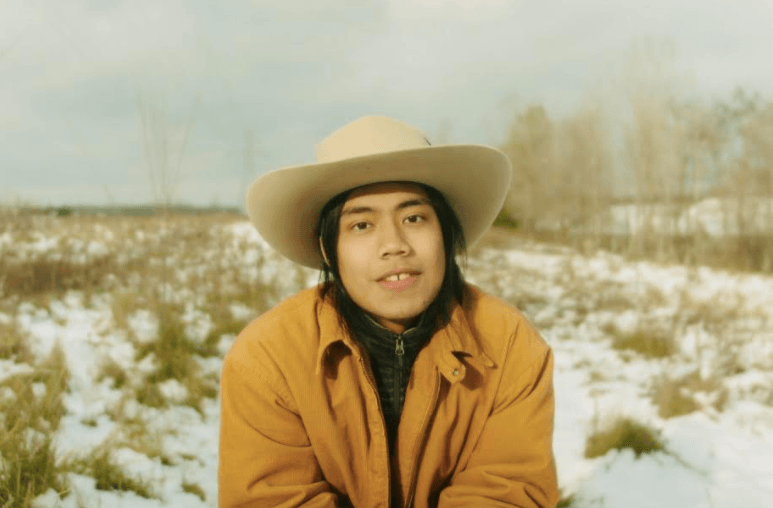

DAGUPAN CITY, Philippines — When Don Josephus Raphael Eblahan found out his short film The Headhunter’s Daughter got into Sundance, he was in a hotel room in New York City for his brother’s birthday. His partner Hannah Schierbeek, the wonderful producer for all of his films and a filmmaker in her own right, received an email that made her gasp, forcing everyone’s heads to turn out of concern.

“She didn’t even have to say that we got in — her face said it all!”

I first came across Eblahan’s work through last year’s Gawad Alternatibo. The program had screened his second short film — Hilum. A Kickstarter-funded project initially meant as a proof-of-concept for a feature-length film, Hilum told the story of Mona, a young woman living in a coastal village in Visayas being trained by her mother to become a professional mourner. After being publicly reprimanded for her crocodile tears, Mona seeks the help of an albularyo, and as her walls begin to crumble, I found myself, like Mona, reduced to tears. The film won the Student Prize and received Special Mention from the International Jury at the Clermont-Ferrand International Short Film Festival.

His third film takes the story away from the coast and towards the mountains. The Headhunter’s Daughter follows Lynn (Ammin Acha-ur), an aspiring country artist who goes to the city to audition for a televised singing competition. Aside from Sundance, the film will be having its European premiere at Clermont-Ferrand, the second-year in a row for Eblahan (“Apparently, it’s rare to go ‘twice in a row’ so this acceptance really humbles us”).

With 8,050 miles between us, I spoke to Don via a written interview to talk to him about his beginnings in filmmaking, living in liminality, finding inspiration in music, and bringing The Headhunter’s Daughter to life. This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

In an interview with The New Current last year, you spoke about how your passion for filmmaking stems from your interest in other art forms. Could you talk about your beginnings as a filmmaker and the transition from one art form into another?

I began drawing due to all the anime and mangas I’ve watched and read as a child — eventually dreaming of maybe one day writing my own comic books. Eventually, I also learned how to play guitar at age 11, which now grew into learning a few other instruments. Having my thoughts sit comfortably in the world of the graphic and the sonic, I eventually began reading books in the headspace of adding sound, visual pacing, and reading like watching a film. Since then, I thought cinema could be an interesting route to go towards.

You grew up in Quezon City and spent your undergraduate years in Chicago, studying at DePaul University. What was that adjustment period like and how did it influence you creatively?

I was born in QC and grew up going to Catholic school in San Juan until the fifth grade. My family eventually moved to and lived in La Trinidad, until the time came for me to leave home to pursue film studies in Chicago. My relationship with being in between worlds and sort of traversing this liminal space of geographical divide is something I hold heavily in my thoughts. Perhaps it shows in my characters as well, but echolocating my place in this world has been quite a neverending act. Being in the West has held up a mirror towards myself, perhaps instigating a reason to be more inquisitive about my own identity, the history of the land/or islands I grew up in, and the interpersonal and spiritual voices that call for their stories to be told.

All your shorts have an intimate, poetic, and dream-like quality thanks to some recurring formal qualities — the square frames, the signature haze and glow, and the sound design whose ebbs and flows moves along with the inner life of your characters. How did you arrive at these audiovisual signatures and what films/which filmmakers influenced your craft?

At this point, these technical and aesthetic choices linger toward muscle-memory territory. They’ve become an unconscious thought pattern that when I write — I write according to these parameters, that my scripts tend to verge on looking like a shot-list in prose. Perhaps it’s a comfort zone and I do aim to break it but for now, my themes, characters, and ideas sit comfortably in this audiovisual space. It’ll be interesting to see how they’ll unfold when I push the box a little wider.

Drawing from autobiographical tendencies, my works revolve around memories, trauma, and characters who traverse a landscape that urges them to go where the stories would eventually unfold. The nostalgic effect of having weathered, small, and geologically architectured images lends itself to tell stories that explore these sensibilities with much more flow. I’ve seen this audiovisual approach in filmmakers from many cinematic traditions around the world, and I attribute my inspirations from Italian Neorealism, Polish cinema, and Japanese cinema. There’s so many to name, yet films from these regions strike a chord in me, as much as our own films in the Philippines do. I adore films where there is a constant collaboration between the landscape, it’s memories, the characters, and the filmmakers.

Your work explores themes of trauma, spirituality, and nature through the cosmic lens of post-colonial spaces and Indigenous identities. Why do you gravitate towards these themes and this lens of interrogating your stories? How do your Ifugao and Visayan roots influence your filmmaking and the kind of stories you shed a spotlight on?

So many thoughts about my identity went untapped, until I found cinema as a vessel. Similarly, it took me until after I felt alienated from my homeland, and living in the West while studying film, that I felt ready to come home and create films that explore ideas that spoke to me when I was younger: growing up half-Igorot, moving from a big city to a rural region, having different cultures raise me, and having tragedies shape the way I see the world today. The vast concepts of colonization, memories of the land, historical subjugation of mass groups of people from all over the world have become concepts that feel closer to me the more I remind myself of my indigenous roots — and I aim to make stories where my people, their voices, their bodies, and their landscape all lend themselves as a fragment to the collective Filipino narrative.

How has music shaped your filmmaking?

Music is an integral part of my methodology since I always begin my writing process by listening to and making music. Once I have reached a musical headspace where themes and ideas I care about start morphing into a “music video” in my head, then I develop it as a narrative and begin putting it all in writing.

My frequent musical collaborator and Sound Designer Henry Hawks approaches our post-sound process musically the same way I tend to. Placing as much care and attention to texture, rhythm, and tone in the mixing and score composition, we work closely in approaching sound as our way of telling the story beyond the confines of our limited “square-ish” frame.

What was the development process like for The Headhunter’s Daughter? Looking at the credits, I know that you wrote, directed, shot, and edited the film. Did the story and treatment change because of pandemic constraints?

Development began two years ago when I came up with the idea of the character who traverses the threshold of two cultures: the Igorot identity of the Cordilleran North, and the Neo-Westernized cowboy culture brought by the American colonization post-Philippine-Spanish War. This character has morphed and shifted multiple times until I crossed paths with the lead actor Ammin Acha-ur whose life story closely resembles the character that I have crafted for years before I had met her. From there, the story’s pieces kept falling into their rightful places even down to the last shots of our production.

We kept rewriting and adapting depending on what we were allowed to do during the pandemic as well as what nature had brought for us during each day. Even the final scene is purely accidental as the typhoon had just hit right as we were filming our last shots — we gravitated to what the landscape had given to us. Being a very low-budget production during the pandemic, we had to minimize contact and involvement as much as we could. Which means the max number of our core crew members were four, which sometimes grew to eight depending on how much help we needed for a particular scene. I had to resort to assuming multiple roles, including writing and performing the music featured in the film’s diegetic world, and multiple folks in the crew had to do the same, as reflected in their credits as well.

The film begins with a duet of the song “Down in the River to Pray.” Why’d you choose this song and this scene to open the film?

Off the bat, I wanted to give context of the colonial influence that is ever present in the Cordilleras. Besides the atmospheric textures it provides to set the cinematic tone, I wanted this historical context to be introduced from the very beginning, even before any visuals are seen. To linger around this context before the film emerges from the black screen sets a precedent that urges participation with the audience to listen closer and perhaps situate themselves in a historical and sociological headspace before we introduce any direct narrative.

The song is adapted from an old African-American hymn. Its original lyrics have changed over the years but I simply fit it to the geological landscape of our film. It’s important for me to pay homage and respect to the roots of country music and how it originated from enslaved African voices and their musical practices that carried their stories throughout many generations to come. The Ifugaos have the similar traditions of the Hud-hud. Passing along memories and stories through songs around the warmth of the flames and the community that lends their strength and voices to foster our terraced lands for hundreds of years. Perhaps this is why Cordillerans love country music so much.

Within the first minute of Headhunter’s Daughter, it shows the calendar in 2021. We also see that Lynn, the protagonist, participates in a singing contest at an empty bar. What made you decide to set the film in the “present?”

Besides having the calendar be a pre-existing item in the home that we filmed in, I wanted to leave it where it exactly is, perhaps hoping that we also mark ourselves into the larger narrative of the world moving forward during the pandemic. There was a special interaction and unspoken collaboration between our production and the “present.” Our film inevitably shaped itself as how it is now due to the unbearable weight of the “present” and the challenges and unpredictability it brought to our lives, and as any fruitful collaborator, we’d want them to make their presence known in the film.

I thought it was moving how Lynn joins the competition not for money, but so her father can see her on the television. What made you decide to interrogate the intersection of television and country music and the life of Indigenous families?

The intersection between Indigenous identities and TV hasn’t always been the friendliest (even Philippine TV) — from caricatured portrayals, to insensitive remarks about our culture. For Lynn to be interrogated point-blank on-screen draws attention to our media’s tendency to sensationalize the othering, the tragic, the sappy, and the unfortunate in Indigenous Filipinos’ lives. I wanted to show a character that offers a different response and perspective towards this cyclical trend. Lynn’s choice to approach her audition in that cadence shows a type of covert resilience that I believe was needed in that situation.

In both Hilum and The Headhunter’s Daughter, you shine a spotlight on female protagonists and their relationships with their parents. In both of those films, they begin by chasing after some dream but it ends with them realizing the importance of home and her family. What’s the importance of this “act of returning” in your work?

As someone who has moved around multiple regions, and now have been living in the middle of two vastly different and historically charged societies, I find myself in a perpetual act of returning. Growing up, raised mostly by women, I have learned to see the world the way they taught me how to traverse it, perhaps lending towards my impulse to write/cast for female protagonists.

You’ve spoken about how Hilum is inspired by some of your own experiences. Does The Headhunter’s Daughter have parallels to your own life, especially considering your foundations as a musician?

My background in music means so much to me that I wanted to express my love for it through this film. It was always music before filmmaking, and my dreams for it never really faded, and now they live in the character of Lynn. – Rappler.com

The Headhunter’s Daughter is having its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival from January 20-30, 2022. For more information and for ticket prices, visit the Sundance Film Festival website.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.