SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Spoilers ahead.

The EDSA People Power Revolution marked its 37th anniversary last February 25. The uprising is often touted as “bloodless,” but it is far from it, precisely because toppling the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and his cronies did not happen spontaneously and cannot be reduced into a singular four-day event at EDSA. If anything, the uprising anchored on years of bloodshed — tortures, killings, and enforced disappearances — under martial rule. By looking into digital repositories such as the Martial Law Museum, Martial Law Index, Arkibong Bayan, and Bantayog ng mga Bayani’s “mosquito press” library, one could already measure how the Marcos dictatorship shaped Philippine history for all the wrong reasons, and forged the path for populist leaders and the ever-growing culture of impunity that Filipinos, wittingly or unwittingly, continue to reckon with.

Ironically, the dictator’s son, who is now sitting in Malacañang, extended his “hand of reconciliation” and offered a wreath of flowers at the People Power Monument during the commemoration. He said he was “one with the nation in remembering” the ouster of his father. This, despite the Marcos family’s unrecovered ill-gotten wealth. This, despite their active efforts in distorting history through state propaganda, including arts and cinema.

Because of this socio-political condition, initiatives aimed at confronting the historical whitewashing that we find ourselves in and holding people in power accountable become all the more necessary. Director Joel Lamangan (The Flor Contemplacion Story, ZsaZsa Zaturnnah Ze Moveeh), bearing this in mind, uproots the Marcoses’ final hours at Malacañang and uses it as a premise for his latest work Oras de Peligro.

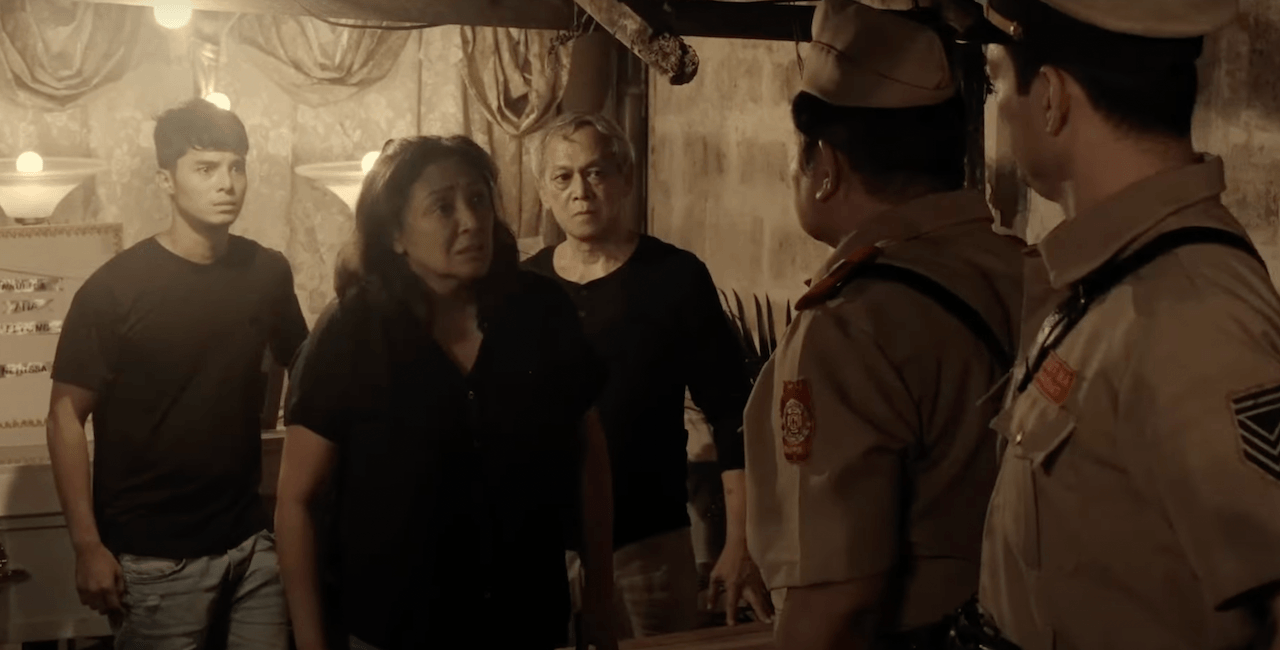

Banking on open defiance and overt political message, the film sets the tone by opening with footage and newsreels of nationwide unrest following the 1986 snap elections, marred by fraud and discrepancy. Caught in the situation is Dario Marianas (Allen Dizon), a jeepney driver who decides to join a transport strike. But his wife Beatriz (Cherry Pie Picache) refuses to take part in any form of social action. “‘Wag na tayo sumali sa mga ganyan, kumayod na lang tayo nang kumayod (Let’s not get involved in such things, let’s just work harder),” says Beatriz. But the signs of the times are becoming more difficult to ignore, especially for their two children, as Jimmy (Dave Bornea) struggles to land a job, while Nerissa (Therese Malvar) takes interest in frequent demonstrations in her university. Things later take a huge turn for the Marianas family as Dario gets killed by personnel of the Philippine Constabulary Metropolitan Command, notoriously known as MetroCom, in a holdup incident.

Lamangan lays bare his positioning from the get-go, assured that, by telling a grassroots story of Martial Law violence, Filipinos will make a better sense of the uprising that took place at EDSA and, by extension, the nation’s historical amnesia. That in itself is an interesting route, if only Lamangan had cemented it with more competent filmmaking.

Editor Gilbert Obispo’s sloppy cuts between a huge chunk of footage, news headlines, and the story at hand gets in the way of the film’s storytelling, particularly in moments when its emotional heft is about to take a leap. The sound design, wielded by Fatima Salim, whose idea of impact is to be imposing and stick out like a sore thumb, also doesn’t provide the material any help. Of course, it is understandable that the screenplay, written by Bonifacio Ilagan and Eric Ramos, tends to cover all the bases. After all, Ilagan carries with him a gnawing awareness of what it means to endure life under the elder Marcos’ reign of terror. This tendency, however, turns Oras de Peligro into a piece defined by its parts, struggling to create a cohesive, more nuanced sum. The film would have been far more solid with better focus.

If one can believe it, even an actor as talented as Picache delivers a less convincing work, resorting to an acting technique informed by so much whimpering — a lapse made more apparent by the dialogue that ends up too contrived, if not clunky. This oversight extends to other scenes, including those that highlight Mae Paner’s Doña Jessa, who winds up more like a caricature, especially in her “Mambo Magsaysay” moments, than a densely written character.

But for all its misfires, Oras de Peligro commits to its intention in interrogating how lies, when told many times over, can become more seductive than truths; how marginalized communities are always the first ones to endure injustice inflicted by the very system it once trusted; and how history necessitates retelling but not rewriting. But it has also been said before that intention alone cannot make a film hold water, and considering the magnitude of trauma and struggles the Marcos regime has cast on tens of thousands of lives, the more we should clamor for better ways to articulate it, the more we should demand better work from filmmakers and cultural workers.

Yet there is something amiss when all that comes out of the state’s relentless propaganda and historical distortion is more craft, precisely because it is a systemic problem that requires reckoning beyond craft. Of course, this is not to say that cinema, or any work of art, is futile. But it should not be the only space where we can stake our rights, which have long been disregarded by tyrants and their cohorts. The ending says it best: We should take the struggle to the streets. Because, again, art can only do so much.

If it isn’t any clearer, transitional justice for Martial Law survivors would only be possible with laws that would place the Marcoses behind bars, with an educational system that acknowledges their struggles and competently teaches history, with a media that doesn’t cave in to the network of neglect, and with a culture that puts stories of people who have long been sidelined, if not totally erased, front and center.

As Oras de Peligro warrants, danger grows by the hour, so the race to fill in the gaps in the country’s historical memory also becomes a race against time. Our only choice then is to collectively act and make every hour count. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.