SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

If there’s anything that last year’s national elections have made clear, it’s that Marcosian myth-making has national consciousness completely in thrall. They are fluent in the telling, perhaps more so than their detractors, and this fluency forms part of the myriad ways they made their way back to Malacañang. Efforts to counter false narratives have thus far been ineffective in reaching those otherwise apathetic; people are either content to wait it out or are too busy treading water in Marcos Jr.’s Philippines, and neither would have the time nor the resources to care for middling arguments against victors who’ve rewritten history. There is a burden, then, on those who demand attention to deserve it. When they do — and then squander it — it’s a cut towards a thousand, and then death.

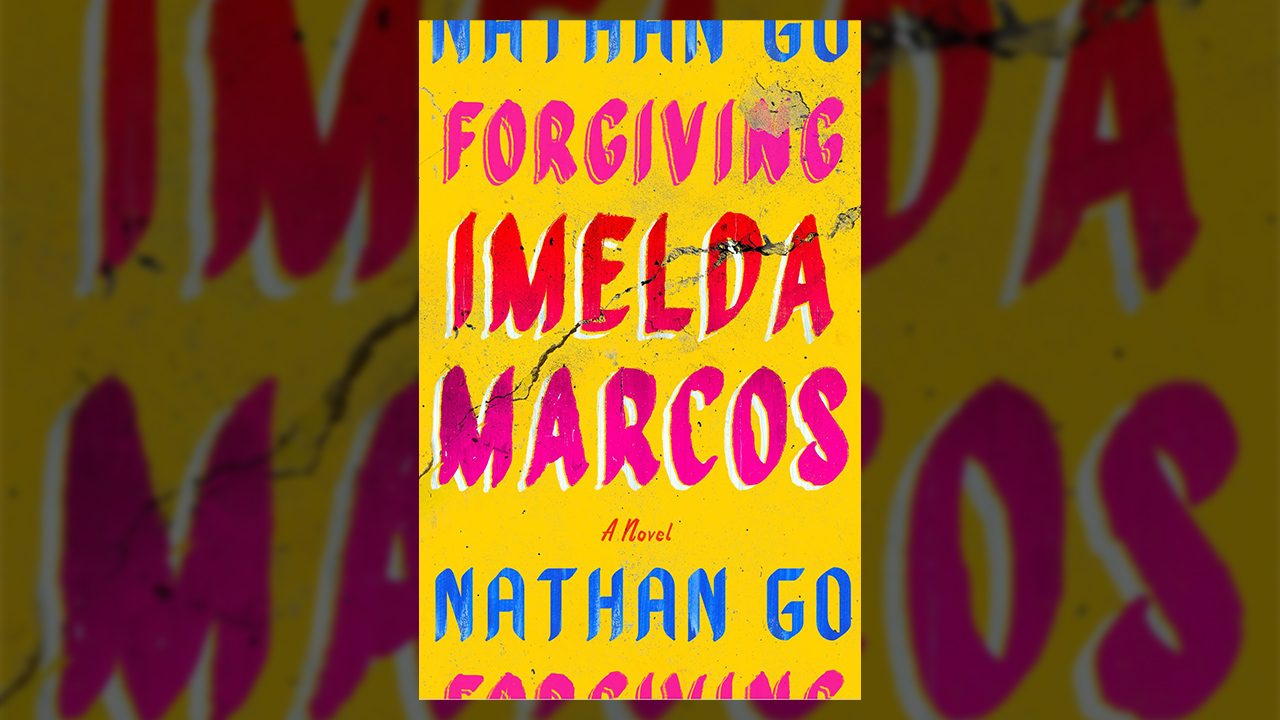

Nathan Go’s Forgiving Imelda Marcos, forthcoming from Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, follows Lito Macaraeg, former driver to an imagined Cory Aquino, who writes long missives to his estranged son in the United States. He has promised something of an exclusive to his journalist offspring: a confession on a journey taken with the former president to meet Imelda Marcos, half to the pair of the conjugal dictatorship. The letter-writer is front and center, contextualized with tangents on his childhood, his experience in the mountains with a rebel group, and life with the Aquinos. For all intents and purposes, this is a deeply personal character-driven narrative. As a meditation on life during and post-Martial Law — and as a last-ditch effort from a father to connect with his son — this is a beautifully written novel that boasts of its Filipino-ness. But as a cultural product in this specific context, it suffers from its vacillation.

On a technical level, the language in the novel is its strength. Go, in the voice of Macaraeg, has a gift for breaking words down to deliver a gut punch. In one instance, he talks about the rice terraces in terms of what its name sounds like – “hagdang-hadgang palayan” – as the very space upon which “you can really hear the clip-clop of someone’s feet ascending or descending.” This attention to rhythm is an homage to the beauty of language in Filipino hands, and the way it is used here to add depth to the character is brilliant. Yet for all that it’s beautiful, it also distracts. The writer is ever in the room, and it wars for attention with his driver-protagonist. (Lito is a learned man, the text makes clear, but some of the word choice points to translation. It is obvious he is talking to an American audience. You wonder then, whether it is Lito speaking, or his journalist son and his editors.)

The story itself is interesting. The narrator has a colorful past, and the work that the author put into characterization means he can be forgiven for his decisions, his stubbornness, his thoughts on matters. There is an episode in the mountains, for example, with the narrator in the company of rebels, that works to justify his politics as an adult. The novel never asks the reader to agree with Macaraeg, but it never asks to be questioned, either. This is especially clear when it falls prey to the fallacy of assuming that an ideology is inherently immoral because of one man’s actions, in this case a communist’s predatory behavior towards young boys. Because Macaraeg is level-headed, the reader is made to assume he’s already thought this through, that his conclusion is sound. And then he moves on to the major players, and the reader is forced to let it go.

In this, the fanciful version of former president Cory Aquino is warm. Their interactions — Macaraeg and Aquino — paint a picture of familiarity: here, the former president is merely a woman, widowed and dying, veiled in quiet sadness and yet capable of laughter. She is firm, but she cares. She is capable of forgiveness. This level of sympathizing for the Aquinos was something unexpected, as given the title, it’d have been more reasonable to assume it of the Marcoses. Mercifully, the latter doesn’t come to pass, aside from some humanizing on the narrator’s part. This is important, even the novel concedes, when false narratives brought them back to power. But the degree to which the Aquinos are praised is in itself troubling. The central conceit reveals this. It falls prey to the myth that Martial Law was between two families and their allies, instead of the Marcoses against the Filipino people. Macaraeg asks, “What makes you think you have the right to forgive Imelda Marcos?” And Go answers that question when he reveals his cards. At any other time, if this were about any other subject, this would have been so good. Alas, we are in the now.

The novel’s greatest fault, however, is that it never earns its title. There’s no forgiving that, not in this political climate. Go, in the voice of Macaraeg, does question it, but there are some things that must be answered. Especially because not everyone can afford the privilege of reading for leisure, and so look at the title as a signal. (This material reality is not the novel’s fault. As the poet Conchitina Cruz writes, “The ordinary Filipino cannot afford to be a reader, and the writer cannot address this fundamental issue by way of craft.” There is, however, something to be said for irrefutable statements in a time of obfuscation. The Marcoses, after all, are good at the spinning. For this to come from a prestige press such as FSG lends a specific literary weight — even credence — to a signal that doesn’t bode well for the continued struggle for justice.)

The shame is that this is a good debut. Its language is beautiful, its characters fully realized. Lito Macaraeg is a convincing narrator. But the entire premise makes it harder to evaluate the novel as a story solely about one man. Here and now, even just the notion of forgiveness sans justice reads insidious. – Rappler.com

Bernice Castro is a fictionist by training and a communications and advocacy consultant by profession, with a special interest in the intersections of narrative, policy, and community engagement. Talk books with her at instagram.com/bernicillin.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] ‘Hating’ Corazon Aquino](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/02/1.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[Hindi ito Marites] First Lady Liza Marcos: Unofficial presidential spokesperson?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/Hindi-ito-Marites-TC-ls-02.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.