SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The Supreme Court is in the middle of intensifying public pressure for action to curb abuses by state agents, particularly the practice among judges who issue search warrants against activists that result in massive arrests and killings.

Just last Sunday, March 7, search warrants resulted in 9 killings all in a day in the Calabarzon area.

Progressive groups now call the issuing courts “warrant factories” because the recent crackdowns were authorized by the same judges.

It was Quezon City Executive Judge Cecilyn Burgos Villavert for the 2019 Bacolod and Manila arrests, and the Human Rights 7 arrests in December 2020.

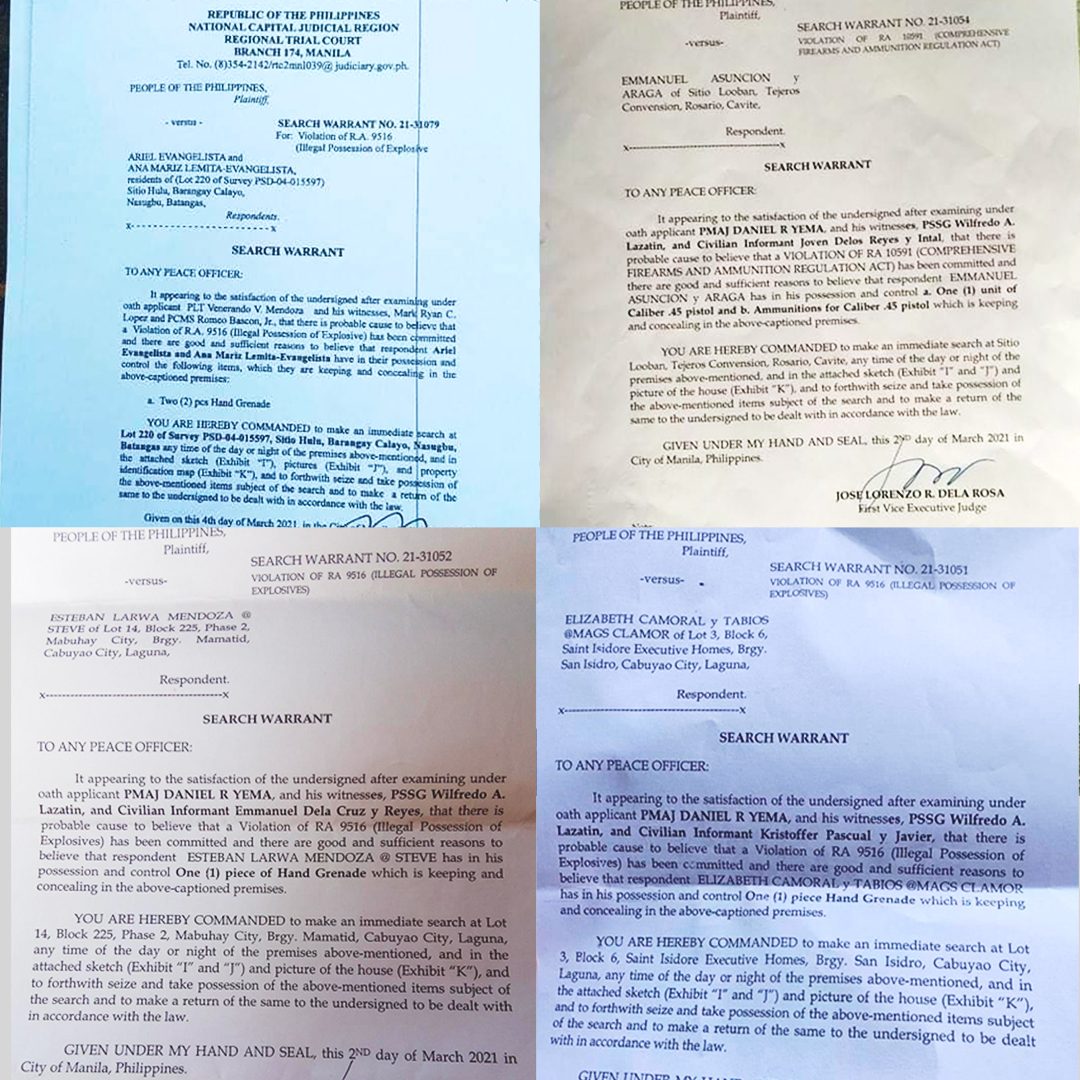

For the Calabarzon killings and arrests, it was Manila First Vice Executive Judge Jose Lorenzo dela Rosa and Manila Regional Trial Court (RTC) Branch 174 Judge Jason Zapanta who issued the search warrants.

These search warrants are usually issued by a judge only if they fall within the same judicial region – for example, a judge in Manila can only issue a search warrant for the National Capital Region.

But by virtue of a Supreme Court circular in 2004, AM No. 03-8-02-SC, the executive judges of Manila and Quezon City, and – in their absence – their vice executive judges, can issue search warrants even outside their judicial jurisdictions.

“We ask the Supreme Court to revisit and put safeguards to the administrative circular allowing Manila and Quezon City executive judges and vice executive judges to issue remote search warrants especially serial search warrants,” said Josa Deinla of the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers.

Deinla said they have observed that one judge can issue several search warrants – a set – in one day, raising questions of how thoroughly the judge examined the police’s application and how carefully he or she scrutinized the affidavits of informants.

Human rights groups have obtained at least 3 search warrants from Judge Dela Rosa issued in just one day for several people.

The general idea for remote warrants is, the farther the court, the lesser the likelihood that the subjects are notified they are about to be searched.

NUPL president Edre Olalia said there’s an urgent need to reexamine this rationale, saying courts in the same locality would be “in a better position to scrutinize the application.”

Examining the warrants

The next remedy for an activist arrested after a search would be to void the search warrant.

This is tricky since it is essentially asking a lower court judge to review the action, or even reverse the action, of a co-equal judge. When charges are filed, they are filed in the court of jurisdiction and usually not with the court of the judge who issued the search warrant.

But even getting records of the search warrant for examination has proven difficult for activists and their lawyers.

At least three lower court judges have shown different standards in treating these cases.

In the case of young activist Reina Mae Nasino, Villavert did not want to give lawyers records of the search application, citing a policy of the Office of the Court Administrator (OCA) that requires a subpoena from the judge handling the main case. The OCA is an office under the Supreme Court, headed by Midas Marquez.

When lawyers sought a subpoena from the handling judge, Manila RTC Branch 20 Judge Marivic Balisi-Umali, they were instead directed to write to the OCA, according to a complaint filed by NUPL against Umali before the SC’s Judicial Integrity Board (JIB).

“To this day we have not received a reply from OCA,” Deinla said in a press conference on Tuesday, March 9.

The wait for the OCA’s reply was overtaken by events as Umali proceeded to arraign Nasino and put her on trial. Nasino’s newborn baby, River, died at age 3 months within that period.

Decisive judges

It was a different case for arrested journalist Lady Ann “Icy” Salem. Her lawyer Krissy Conti of the Public Interest Law Center (PILC) said the handling judge, Monique Quisumbing-Ignacio of Mandaluyong RTC Branch 209, readily subpoenaed the records from Villavert.

“The Mandaluyong judge was decisive and objective enough to grant our motion and issued a subpoena on January 4, 2021. The Office of the QC Executive Judge transmitted the records for two warrants against our client, including the 107-page transcript which covered the three other applications,” said Conti.

The records were crucial to Ignacio’s eventual ruling that voided Villavert’s warrants, after seeing in the affidavits how informants had actually given conflicting accounts.

In the case of activists in Bacolod, while Branch 42 Judge Ana Celeste Bernad did not subpoena the records from Villavert, she conducted an inspection of the property and found that the search warrant was overly broad. Bernad voided Villavert’s warrant, too.

Contrast that with Umali’s ruling in Nasino, saying in a July 1, 2020, order: “The executive judge of Quezon City has in her favor the presumption of regularity in the performance of her official duties.”

“Definitely we need a clear guideline on obtaining these records,” Deinla said in a mix of English and Filipino.

What else can Supreme Court do?

Neri Colmenares of the NUPL said the Supreme Court can make review of the warrants automatic if a death results from the implementation, including requiring policemen to report the circumstances that led to the death.

The OCA can also conduct a judicial audit of these courts.

In 2016, the OCA audited the search warrant applications of Malabon RTC Branch 170 Judge Zaldy Docena and found the judge had issued too many warrants, with few returns to the court. (A return is a report from law enforcers informing the court how they executed its warrant.)

In 2017, the Supreme Court suspended Docena for two years without pay after finding that the judge’s “issuances of the subject search warrants have been motivated by bad faith.”

“A legitimate question the public wants to be addressed is: whether or not the judges issuing these search warrants were clueless, careless, or complicit?” said Olalia.

We asked the Supreme Court Public Information Office if the OCA is considering conducting an audit in the wake of the arrests and killings, but have not received a response as of writing. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.