SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Amanda Echanis knows her “why.”

“Para saan at para kanino? Kung alam mo kung paano ‘yun sasagutin, bahagi ang sakripisyo,” she said.

(For what and for whom [do you fight]? If you know how to answer that, sacrifice is a part of it.)

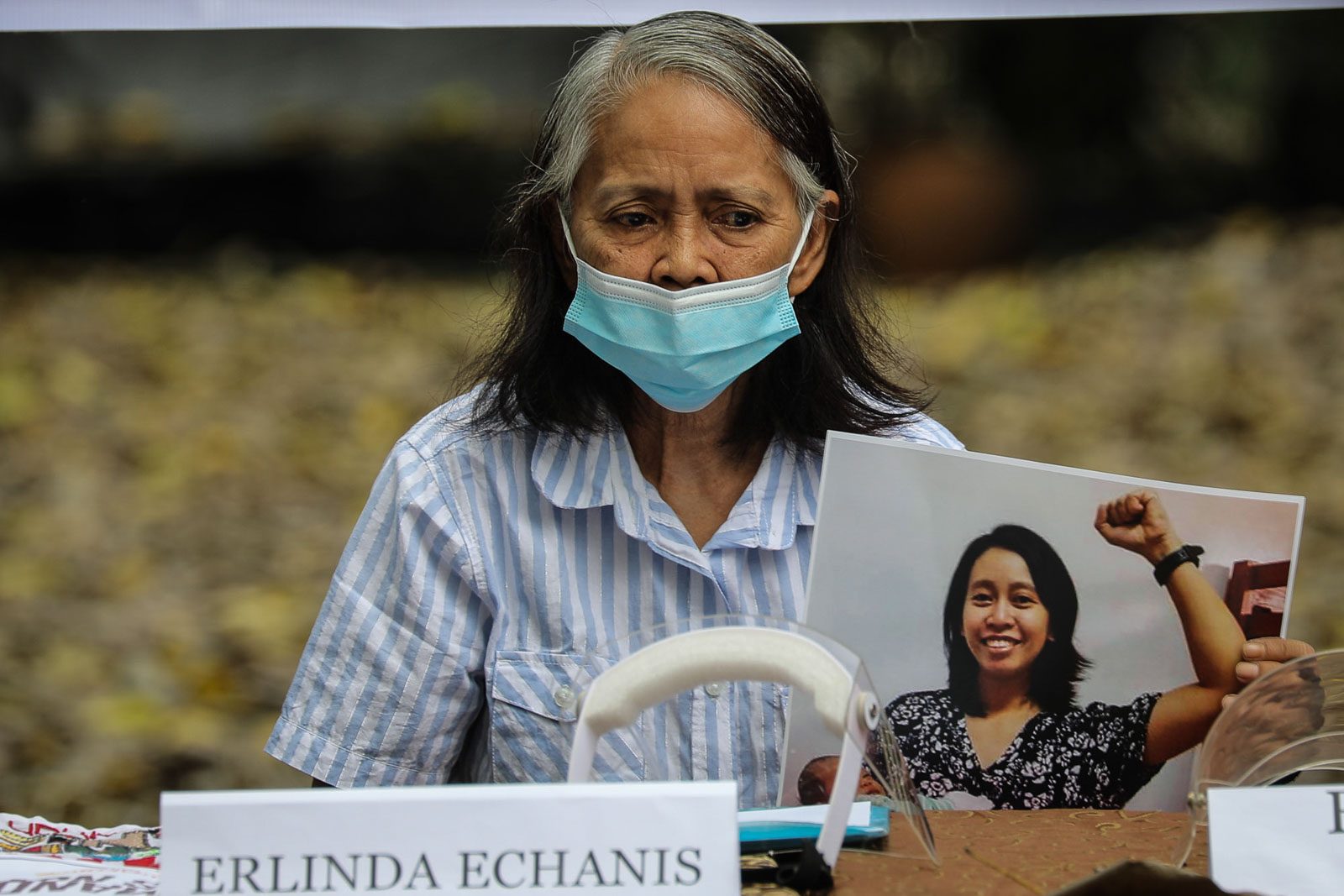

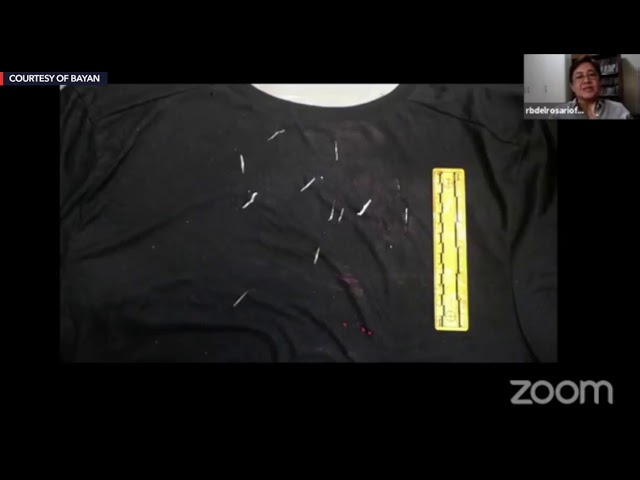

Tuesday, August 10, marked one year since Amanda’s father, longtime peasant leader and activist Randall “Randy” Echanis, was killed inside a rented apartment in Quezon City. Autopsy showed Randy was tortured – stabbed many times – in one of the gruesome murders in 2020 that remain unsolved.

Amanda, 32, was on her third trimester of pregnancy when Randy died. She was in Cagayan, where she had been living since 2016 to organize peasant women, when she heard the terrible news.

Her pregnancy, and quarantine rules that sealed borders in the Philippines, did not allow her to bury her father.

She knew this life. At six months old, she was in jail to join her parents Randy and Linda Lacaba-Echanis when they were imprisoned in 1990 for illegal possession of firearms – the same charges for which Amanda is now behind bars in Cagayan.

It’s the life of a family of activists, that “we knew, during that time, that there was a danger to his life, and to ours. Because he’s my father, the danger was always there, especially under the current administration,” Amanda told Rappler in a letter sent through her lawyer.

But Amanda refuses to concede that death is a fate they must expect, or accept.

“Hindi naman dapat inaasahan ang ganung pangyayari. Pero kailangan maging matatag. Kung saan nanggagaling ang katatagan, ‘dun ‘yung pag-unawa kung ano ba ang ‘pinaglalaban. Babalik dun sa tanong na, para saan at para kanino? Kung alam mo kung paano ‘yun sasagutin, bahagi ang sakripisyo,” she said.

(You shouldn’t be resigned to something like that. But you have to be strong, and that strength comes from understanding what it is you’re fighting for. It will always come back to the question of for what and for whom. If you know how to answer that, sacrifice is just a part of it.)

As of March 2021, there had been 394 activists and grassroots organizers killed under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, according to data from human rights group Karapatan. In the same timeline, there had been 3,790 activists and grassroots organizers charged – more than the number under the administrations of Benigno Aquino III and Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo combined.

The system has not changed

When she learned she was going to have a boy, Amanda said she cried – out of happiness, for sure, but also out of sadness because Randy would never get to know his grandson.

So Amanda named the baby Randall Emmanuel – Randall after her father, and Emmanuel after her uncle, poet and playwright Emmanuel “Eman” Lacaba, who was killed while fighting the Marcos dictatorship.

Randall was born on October 25, 2020. On December 2, the boy was a little over a month old, Amanda was arrested. The police accuses her of being a New Peoples’ Army (NPA) leader – something she vehemently denies.

Peasant group Anakpawis, which Randy chaired before his death, said Amanda’s home was raided unofficially for five hours before police came back to serve the warrant with witnesses present. It was a pattern by the police that activists had long condemned, and which prompted the Supreme Court recently to require policemen to wear body cameras during the execution of warrants.

At one month old, Randall was in jail, even younger than his mother when the latter was detained with her parents.

On October 9, weeks before Randall was born, the daughter of jailed activist Reina Mae Nasino, baby River, died.

River was separated from Reina Mae in a case that put the entire justice system under scrutiny, especially the Supreme Court, for the lack of remedies for mothers in prison.

Amanda watched the baby River news from television. The crackdown on activists was at its peak.

“I thought, what if that also happens to me? So I resolved that, if something unfortunate happened, the most important thing was to ensure we wouldn’t get separated,” said Amanda in Filipino.

Randall is now nine months old, learning how to walk inside the Cagayan Provincial Jail. He’s healthy, says Amanda.

She doesn’t entertain the question of what Randall’s life would have been had she quit activism, if she had written a different story for her son.

“If that’s the framework you work in, it means there’s regret,” Amanda said.

“I don’t look at it like that. We’re here not because I wanted to, but we’re here because they planted evidence,” said Amanda.

“What this means is that the system has remained the same. In fact, it’s gotten more cruel, for this to happen to people who do not deserve it,” she said.

The Department of Justice (DOJ) has a task force on political killings that committed to investigate Randy’s death.

“One year after he was killed, the announced investigation by the Task Force on Administrative Order 35 has yet to show any significant progress towards determination and arrests of suspects,” Karapatan said in a statement on Tuesday.

Hopeful, not fearful

To protect her mental health, Amanda said she has to be the best friend she could be to herself.

Calls via e-dalaw help, she said, and her fellow inmates are a rich source of stories.

A creative writing graduate, and an alumna of the Philippine High School for the Arts, Amanda continues to write inside prison, having already written 15 poems. The last book she read was Macli-ing Dulag by Ceres Doyo, a book about the tribal leader who led the resistance in the Cordilleras during the Marcos dictatorship.

What gets her are her postponed hearings. During the lockdown in Cagayan, they didn’t hold hearings for three months, she said. Video conferences sometimes do not work, as she had once experienced a power cut that interrupted internet for the court.

On July 14, 2021, the judge in her case voluntarily inhibited, said Amanda’s lawyer Luchi Perez. It’s being re-raffled to another court.

“I hope that the regional trial court expedites the hearings,” Amanda said.

Amanda often thinks about the Nelson Mandela quote, “May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.”

“When I’m making a decision, I’m thinking: Am I doing the right thing, like keeping my baby here? Am I being hopeful or am I being fearful? That’s what I hold on to, and I know I’m doing the right thing,” Amanda said.

She doesn’t have a timeline for when she and Randall can get out of jail.

She lives every day on hope – hope, because there is a trend of courts voiding search warrants against activists and her fellow human rights defenders walking free.

“Hopefully, the next judge who will handle my case will see the trend of planting of evidence. I hope the judge rules on fairness and justice, and not bow down in fear,” Amanda said.

“And that’s all I can hold on to now, as well as everyone like me who is fighting for something.”

(The quotes in English have been translated from Filipino.)

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Silent Tragedy: Epekto ng war on drugs sa mga bilangguan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/silent-tragedy-tcard.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.