SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Taking the train in Metro Manila can be an obstacle course involving jam-packed carriages, snaking lines of passengers, and mad dashes up staircases. But for persons with disabilities, it is almost impossible to commute alone.

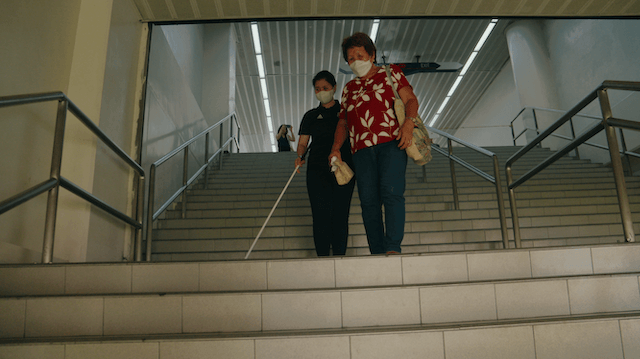

Bless Adriano, a 25-year-old office worker with visual impairment, needs to bring her elderly mother every time she commutes in the megacity. The train system, involving the three lines LRT-1, LRT-2, and MRT-3, lacks facilities to enable her to travel independently.

Adriano, in her commute, must contend with ramps blocked by metal gates, public toilets kept locked, unusable ticket vending machines, and lack of elevators in many stations.

These are just some ways Metro Manila’s train network fails persons with disabilities. Rappler, with the help of accessibility group Kasali Tayo and inclusive mobility group Move As One Coalition, conducted an accessibility walkthrough in all 46 of the megacity’s train stations – LRT-1, LRT-2, and MRT-3.

Conducted on different days from August 7 to 14, the walkthrough sought to assess how the train system meets needs of persons with disabilities who wish to travel safely, independently, and with dignity through the metro.

Videos or photos of persons with disability climbing staircases in train stations periodically go viral on social media. Rappler’s accessibility walkthrough sought to assess the train system as a whole, not just specific stations. It also looked at other facilities or features affecting other types of disability, like visual or hearing impairments, not just mobility impairments.

Rappler found that 80% of train stations lacked fully-accessible entrances for persons with disabilities.

In these 37 stations, barriers of some kind hindered persons with disabilities. In stations like LRT-2’s Gilmore and V. Mapa stations, there were ramps for persons with disabilities but they were rendered useless by gates or metal grills barring any access to them.

In LRT-1’s Doroteo Jose station, both PWD ramps from the street were used as motorcycle parking and led to locked doors. The station’s supervisor told Rappler during a visit that, in the case of one of the entrances, the door has been locked for months because of repairs being done to an elevator. It’s not clear why the same was the case for the ramp in another entrance.

Rappler’s walkthrough involved a physical inspection of all train stations. We drew up a list of facilities or features considered important for PWDs. The list was made with the help of Kasali Tayo, a civil society group composed of persons with disabilities who care about inclusive transportation. Facilities and features in the list were those that could easily be observed by any commuter – like the presence of working elevators and ramps, signages, announcements made, types of flooring used, and the like.

Unlike an accessibility audit, we did not take measurements of facilities.

LRT-1, LRT-2, and MRT-3 management were not told in advance of the walkthrough.

Later on, we visited specific stations with members of Kasali Tayo and Move As One Coalition who have disabilities – visual and hearing impairments, and physical disability. Adriano, lead convenor of Kasali Tayo, was among those we commuted with on August 15.

A majority, or 67%, of train stations had working elevators. But in at least seven of them, mostly in the LRT-2 line, a street-level elevator was present in only one entrance. This means that if persons with disability wound up in another entrance, they would have to find their way to the one with the elevator. This is no easy task as, in many cases, the two entrances are bisected by the busy Aurora Boulevard where persons with disabilities would have to contend with fast vehicles and pot-holed roads.

In response, the LRTA Public Relations Division, in an email to Rappler, said the LRT-2 line was built in the 1990s “when the surrounding streets were not yet busy, with no island barriers.” The LRTA runs the train line.

They also said entrances of stations are connected by a common concourse, allowing a commuter to reach another entrance from within the station. However, this does not address the problem faced by, for instance, a commuter in a wheelchair, who tries to use an entrance without the elevator to the concourse.

LRT-1 was the worst performer in terms of accessibility via elevators. Only five, or a quarter, of its 20 stations have elevators. For the rest, wheelchair users would need someone to carry them and their wheelchair up flights of steps to the concourse and platform.

LRMC, the entity that runs LRT-1, cited limitations in space for elevators as reason for this problem. Those stations they were able to install elevators in entailed leasing spaces in nearby buildings.

“We continue to explore this same option for other LRT-1 stations, but this entails negotiations with real estate surrounding the LRT-1 stations,” said Jacqueline Gorospe, LRMC’s head of corporate communications and customer relations, in an email to Rappler.

How about PWD-friendly comfort rooms? Some 40% of stations lacked these. Rappler considered a comfort room PWD-friendly if it was specific for PWDs, featured handrails, and had sufficient space to accommodate needs of PWDs. But even the comfort rooms that met this minimal standard were problematic for other reasons.

One Santolan Station (LRT-2) comfort room lacked any sign that indicated it was for PWDs. Some, like those in Anonas Station (LRT-2) and Roosevelt Station (LRT-1) were locked during the walkthrough and could only be opened upon request, according to staff present. Others were behind a cordon or a police desk, as was the case in Pureza and Recto stations, respectively, both of LRT-2. In Balintawak (LRT-1), maintenance staff said both PWD toilets were kept locked and unused, except for storage.

But according to Gorospe, these two PWD comfort rooms were kept locked because of instances when passengers who were not persons with disability started using them.

“We have already discussed how we can improve this process, and it was also raised that there is a need for us to include an improved signage to emphasize its use for PWD,” said Gorospe.

Still, persons who don’t have disabilities usually not have to go through the added hassle of asking train staff to open locked toilets. Though possibly well-intentioned, it is yet another barrier unique to persons with disabilities.

The LRTA said the cordon at the Pureza PWD toilet was intended to guide commuters lining up for tickets, but it has since been removed. They also said they have already placed a new PWD facility sign in Santolan Station.

Again, LRT-1 fared the worst in terms of PWD-inclusive comfort rooms. Eighteen out of 20 stations or 90% of stations lacked PWD-inclusive toilets. Most stations had tiny single comfort rooms, with floors that were higher than the station floor yet lacked a ramp for PWDs. Many lacked appropriate handrails.

Architect Armand Eustaquio, who specializes in PWD inclusivity in built structures, emphasized the health consequences to persons with disabilities who can’t find accessible toilets in public places.

“Rather than going down on all fours, crawling on a public toilet to access a toilet because the wheelchair cannot get in, they hold it. They stop it. So, kidney stones, kidney disease, that’s what happens to them,” he told Rappler in an interview.

Inconsistency in tactile flooring, announcements

Commuters who have visual disabilities rely on information relayed through sound to find their way to their destination, purchase tickets, and be warned of hazards.

In Metro Manila train stations, the most important announcements are about approaching trains and safety reminders related to it, like closing doors and gaps between platform and train.

Unfortunately, sufficient announcements were observed in less than half, or 43%, of train stations. In most cases, these key announcements were made by guards on platforms. In some stations, guards consistently and with sufficient volume and clarity made these announcements. In others, guards didn’t make any announcement whatsoever, or merely used their megaphones to make beeping sounds, or announced only the station name after the train had made a full stop. The last two circumstances were true in half of LRT-1 stations.

Inconsistency in these crucial announcements is bad news for persons who depend on audio information. Not being able to predict when and how this information will be relayed to them could be confusing, anxiety-inducing, and dangerous for persons with disabilities.

Inside the trains, the amount of information for commuters was also unpredictable. There were carriages, mostly in LRT-1, that lacked even the route map for the line. In LRT-2, there was always a route map in carriages we rode, but they were all outdated – they lacked the two new stations Marikina-Pasig and Antipolo. LRT-2, however, gets points for having an automated announcement system in all its train carriages, a big boon to persons with disabilities waiting to know which station is up next.

Persons who have a visual impairment use tactile flooring to independently find their way around. Unfortunately, only three out of the 46 stations had a sufficient network of tactile flooring – tactile flooring that is unobstructed and links key parts of the train station – entrances, exits, elevators, ramps, comfort rooms, ticket vending areas, platforms. These three stations are LRT-2’s Santolan station and its new stations Marikina-Pasig, and Antipolo.

But most LRT-2 stations and all of MRT3 and LRT-1 failed in this regard. They were either obstructed by standing signages (as was the case in LRT’s Katipunan Station), were incomplete, or did not lead to key areas for PWDs like the courtesy areas for them on the platforms.

LRTA said the standing signages blocking tactile flooring in Katipunan Station was necessary for the safety of commuters.

“This measure was taken after some passengers mistakenly rushed towards the wrong area, mistaking it for their train boarding area,” they said.

MRT-3 had no tactile flooring at all, in any part of its stations. In LRT-1, only two stations had these but they were very limited and did not cover all essential parts of the facilities. LRMC said tactile flooring for the rest of the LRT-1 stations is “already in the pipeline” and is scheduled for implementation by its engineering team.

Ticket vending machines, warnings about hazards

One PWD-inclusive feature the entire Metro Manila train system fails at is the provision of ticket vending machines that have tactile buttons, braille, and text-to-speech functions. All machines were touchscreen, which is difficult for persons with visual disability to use unless they are assisted. If they were commuting alone, they would need to go to the ticket tellers, often preceded by long lines, especially during rush hour. They would need to line up at the ticket tellers anyway to avail of their PWD fare discount as this cannot be availed of using the machines.

The ticket vending machines in all train stations come from a single supplier, AF Payments Inc. Suggestions have been made to use more inclusive ticket vending machines.

The LRT-1 line is unique in that all its train carriages we observed were higher than the platform. Platform guards said they would push or carry wheelchair users up onto the train. No ramps are used, they said. This presents yet another barrier to persons on wheelchairs who wish to travel independently.

Maintenance of stations to protect persons with disabilities was also found severely wanting in several instances.

In LRT-1’s Central Station, large puddles by entrances were observed after a morning of rain on August 14. There were no caution signs or audio warning given to adequately safeguard persons with visual disability.

LRMC’s Gorospe called the puddles in Central Station an “isolated case.”

“We would like to apologize for the inconvenience caused. Upon checking with our janitorial services provider and Admin team, the cleaning personnel was still mopping the other damp areas,” she told Rappler, adding that the train line’s usual protocol involves continuous mopping of floors and provision of absorbent materials or matting to avoid falls.

On the bridge from LRT-2’s Recto Station to LRT-1’s Doroteo Jose Station, there were no such warning devices either for a large covered obstruction that ate up almost half of the pathway for commuters.

Tiles here were broken, creating holes or breaks in the floor that, while imperceptible to others, could spell pain and injury for commuters dependent on a white cane, according to Adriano, a white cane user.

“There are areas where there are suddenly etchings or cracks in the tiles. Though these may be so small as to be unnoticeable, as a white cane user, it’s important to me that the tiles are smooth because my cane can hit the cracks and hurt me,” said Adriano.

Maureen Mata, a longtime accessibility advocate who represents persons with disabilities in the National Anti-Poverty Commission, said making transportation systems inclusive benefits everyone.

“When it is accessible for persons with disabilities, it is accessible for all. The reason why we are not going out of our houses and commuting is because of the lack of accessibility of our transportation system,” she told Rappler.

“It is important that we are included and not left behind when it comes to implementing policies that are for the good of all. As they said, it should be nothing about us, without us.”

There are 1.4 million persons with disabilities in the Philippines, according to the 2010 Census of Population and Housing. A more recent survey, the 2016 National Disability Prevalence Survey, found that 12% of Filipinos aged 15 and above live with a severe disability while 47%, almost half, experience a moderate disability.

LRT-1, Metro Manila’s oldest train line, is operated and maintained by a private entity, the Light Rail Manila Consortium. This consortium is made up of Ayala Corporation, Manny V. Pangilinan-led Metro Pacific Investments Corporation, and Macquarie Infrastructure Holdings (Philippines) Pte Ltd.

LRT-2, meanwhile, is operated by a government corporation, the Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA). This company is attached to the Department of Transportation.

MRT-3 is operated and maintained by a private company, Metro Rail Transit Corporation (MRTC). For this, the DOTr pays the company a monthly fee. This arrangement is set to lapse in 2025.

Government is considering turning over operation and maintenance of MRT-3 and LRT-2 to private companies while the train lines themselves will still be owned by the government, as is the case with LRT-1.

Reliance on human touch amid lack of facilities

Metro Manila’s train system relies heavily on human resources to make up for a lack of facilities for persons with disabilities.

Guards are relied upon to make announcements on platforms. They are necessary for assisting persons with disabilities from entrances to trains. They radio each other across stations so persons with disabilities can get assistance in their destination station.

The human touch is necessary and well-appreciated by persons with disabilities, but too much reliance on them, without providing infrastructure or automated systems, is a weakness.

What if many persons with disabilities all ride at the same time, overwhelming the staff? What if a person with a disability wishes to travel alone or commute without asking for assistance? Independent travel is a right that, at present, only persons without disabilities enjoy in Metro Manila.

The consistency of announcements also suffers from over-dependence on guards. As was seen in the accessibility walkthrough, some guards fail to make the announcements that persons with disabilities rely on. Such inconsistencies in implementation could be solved by an automated announcement system.

LRTA said “action is now being done” so that recorded announcements would be played in its train stations’ public address system.

The overall failure of Metro Manila’s train system is its lack of consistency and predictability. Elevators in some stations, none in others. PWD-inclusive public toilets in some, none in others. Limited tactile flooring, missing signages and route maps. Not knowing what to expect in the stations you are heading to makes train commuting stress-inducing and dangerous for persons with disabilities.

The systemic shortcomings in Metro Manila’s train network boil down to two problems: lack of policies and shortcomings in implementation.

How you can help solve the problem

The basis for PWD facilities in train stations is the country’s Accessibility Law, Batas Pambansa Bilang 344 (BP 344). Unfortunately, it hasn’t been updated since 1994.

Architect Armand Eustaquio, who helped write the law’s Implementing Rules and Regulations, said a new IRR has already been crafted and endorsed to the heads of the Department of Public Works and Highways and Department of Transportation (DPWH and DOTr).

The heads are Secretary Manuel Bonoan and Secretary Jaime Bautista, respectively. You can write to them, urging them to expedite the approval of this IRR and implement it vigorously. You can send letters to these email addresses: bonoan.manuel@dpwh.gov.ph and jaime.bautista@dotr.gov.ph or osec@dotr.gov.ph.

What’s in the proposed IRR? According to Eustaquio, it includes more updated features like requiring three types of tactile flooring for people with visual disability: warning, directional, and positional tactile blocks. It would require buildings to have assistive hearing systems or induction loops for persons with hearing impairment to find their way around buildings using their hearing. Those with physical disabilities would benefit from two-way ramps, instead of the common but inadequate single ramps.

But even this proposed IRR lacks guidelines for transportation vehicles themselves. They cover only the stations, or buildings and terminals where passengers board the actual train carriages. A completely different IRR is required for the trains themselves, an IRR that would also cover other conveyances like buses, jeepneys, and boats.

Meanwhile, new policies for PWD-inclusive mobility are being worked on by various groups. Maureen Mata of Move As One Coalition and a PWD representative in the National Anti-Poverty Commission said an executive order has been proposed to President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. The draft executive order would tell all relevant government departments and agencies to fully implement laws related to PWD rights and welfare.

Other efforts include a proposed law from Senator Raffy Tulfo, Senate Bill No. 1700, that seeks to amend the Accessibility Law. Read or download it here.

Ira Cruz of Move As One Coalition said the public can push officials to act just by talking about the issue. Discuss the ills of the train system among friends and family, be vocal on social media. Very visible public clamor can convince senators and members of Congress to convene relevant committees (like the Senate Committee on Public Services and House Committee on Transportation) and work on relevant bills.

Move As One Coalition, a group advocating for better public transportation for all, is calling for the creation of a Commuters Welfare Office and a Commuter Bill of Rights. If this move interests you, you can read below the proposed bill drafted by AltMobilityPH, a member of the coalition.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Under 3 Minutes] When will we see modern jeepneys on the road?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/francisco-motors-modern-jeepney-prototype-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=590px%2C0px%2C1012px%2C1012px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.