SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Conclusion

Part 1 : History in crisis: Easier for students to fall for disinformation in distance learning setup

MANILA, Philippines – Before the pandemic began in March 2020, social studies teacher Jamaico Ignacio said he had an encounter with a student, who enthusiastically approached him after class to show a material sourced from the internet.

“Tuwang-tuwa siya. Sabi niya, ‘Sir alam ‘nyo po ba na si Jose Rizal ay anak ni Hitler? Noong una akala ko nangto-troll siya. ‘Sigurado ka ba diyan?’ Pero when I checked his reaction, he was enthusiastic, naniniwala siya talaga. Then he printed a copy of where he got the info. It was a blogsite,” Ignacio recalled in an interview with Rappler.

(He was really happy. He told me, “Sir did you know that Jose Rizal is the son of Hitler?” At first, I thought he was just trolling me. I asked him, “Are you sure?” But when I checked his reaction, he was really enthusiastic, he really believed it. Then he printed a copy of where he got the info. It was a blogsite.)

It was easy for Ignacio to correct false information back then, when he could confront his students in person.

“Sabi ko sa kanya, ‘Anak, may problema sa dates. Hindi tugma kung kailan [namatay] si Rizal at kailan ipinanganak si Hitler. It took some time to make an impact on the kid kasi sobrang hangang-hanga siya sa nakita niya online. Ngayon mas nakatutok na ang mga bata sa online, and that is where the problem lies,” he said.

(I told him, “Son, there’s a problem with the dates cited. The date of Rizal’s death and the date of Hitler’s birth don’t jibe. It took some time [for the correction] to make an impact on the kid because he was really impressed with his discovery online. Now that the kids spend more time online, that’s where the problem lies.)

But even before disinformation became rampant on social media, Ignacio said social studies teacher like him were already facing challenges with teaching history to students.

Bring back history lessons

Philippine history was removed from the core curriculum of instruction of araling panlipunan (social studies) in the junior high school and senior high school through a Department of Education (DepEd) order in 2014.

Ignacio, who leads a movement to bring back history classes, told Rappler that a dedicated Philippine history subject for high school programs in the country will recalibrate students’ critical thinking skills and digital literacy skills at a time when disinformation is rampant on social media.

Under the current curriculum, there’s no dedicated Philippine history subject. It’s only included as a topic in Grade 5 and Grade 6 social studies subject.

Ignacio explained that teaching history is a lot complicated than it seems since it needs retention in students so their critical thinking would have been honed by they time they reach college. (READ: [OPINION] The slow death of Philippine history in high school)

“The context of the now is that we have 15-year-olds that fall for fake news at kung ganon ‘yung kaso, dapat ganun ‘yung response (so if that’s the case, then the response should address that). One solution is to provide a Philippine history course that is targeted at honing the skills of the students. Kasi tayo alam natin na those are fake news, but for some students totoo siya,” he said. (We teachers know those are fake news, but some students think they are true.)

But for Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) executive director Love Basillote, adding history subject isn’t enough. She said that the bigger problem is not having enough good content for Philippine history.

“We need to teach history better and well. We don’t even have textbooks for history. It’s a bit limiting that we just add a subject, but we need to teach history better with good content. We need good quality content,” she said.

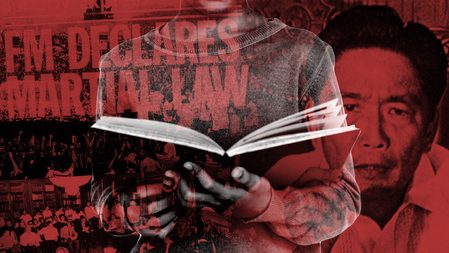

Research from the Far Eastern University Public Policy Center (FPPC), which is part of the #FactsFirstPH initiative, reported that araling panlipunan (social studies) textbooks used by basic education students, specifically Grade 5 and Grade 6 student, don’t have enough coverage of the Marcos administration. They noted that the textbooks contain “little to no discussion” about important topics and events during the 20 years that Marcos was in power.

The DepEd have been explaining that Philippine history competencies found in the curriculum are covered by textbooks and other learning resources distributed to learners.

Open the schools

The recent public conversation on the learning crisis involving the “MaJoha” issue spurred calls for the government to open schools for in-person classes and bring back history classes in high school programs. Critics have said that long school closure is exacerbating the learning crisis in the Philippines. (READ: Briones on ‘MaJoHa’: Learning crisis inherited from past administrations)

Latest data from the DepEd showed that only 40% or some 25,700 of the 60,000 public and private schools have reopened for face-to-face classes. Some schools are having a hard time meeting the building requirements for in-person classes, such as having separate doors for entrance and exit and making available basic health facilities, including hand washing facilities and school clinics.

While experts agreed with DepEd that the learning crisis started with past administrations, they said that Education Secretary Leonor Briones’ administration could have done something to start the recovery.

For instance, the current administration could have been “quicker” in reopening schools for face-to-face classes. But the Philippines was the last country in the world to reopen schools for in-person classes since the pandemic began in 2020.

“For the things that we could have done, in the recent years, we should have reopened our schools quicker. Our neighbors, even [those] who are much poorer than us in terms of GDP (gross domestic product) were able to open their schools quicker,” PBEd’s Basillote said.

A 2021 online survey conducted by the multisectoral group Movement for Safe, Equitable, Quality and Relevant Education (SEQuRE) found that 86.7% of students under modular learning, 66% under online learning, and 74% under blended learning said they “learned less” under the alternative modes of learning compared with the traditional face-to-face setup.

The survey was conducted from June 25 to July 12, 2021, among 1,278 teachers, 1,299 Grade 4 to Grade 12 students, and 3,172 parents.

Data from the World Bank said that the Philippines’ learning-adjusted years of school (LAYS) would be pushed back from 7.5 years pre-pandemic to 5.9 to 6.5 years, depending on the length of further school closures and the effectiveness of the remote learning setup.

This means that while the Philippine basic education system offers 12 years of instruction, Filipino students show proficiency equivalent to only around six years spent in school.

Ignacio believes that the problem now is the faulty K to 12 curriculum that needs to be reviewed.

“Kailangan talaga na i-review na ang K to 12 program kung ito ba ay effective pa lalo na sa mga estudyante. I can only speak for araling panlipunan. I don’t know sa ibang subjects but in this case, tingnan nila ang estado ng araling panlipunan,” he said.

(The government needs to review the K to 12 program, whether the curriculum is effective or not. I can only speak for social studies. I don’t know if this is also the case with other subjects, but in this case, they need to see the state of social studies subject.)

Other ways forward

After reopening schools, another thing that the government can do to recover from the learning crisis is to invest in its teachers, Basillote said.

The social studies teachers Rappler spoke to shared that sentiment. They said that teachers should have “specialized trainings” for their subject expertise. Ignacio said that there were teachers who were not social studies major, teaching history because of the lack of teachers specializing in it. This becomes a problem because teaching historical concepts and events needs to use the right approach.

The same sentiment was shared Project Saysay founder Ian Alfonso, saying that the teachers’ education program needs retrofitting. For instance, graduates of elementary education programs in college don’t have specialization in social studies where in fact they are the ones teaching history lessons under the basic education curriculum.

“Sana the teachers’ education, nag-adjust din, kasi sa BEED (Bachelor of Elementary Education) itinuturo ang Philippine history, pero the graduates of BEED don’t have specialization in social studies,” he said. (The education we give our teachers should also adjust, because it’s the graduates of BEED who are teaching Philippine history, but they don’t have specialization in social studies.)

Project Saysay is an advocacy group that aims to “propagate relevant, useful, and inspiring information – in print and online – sourced from Philippine history.”

Basillote acknowledged that the learning crisis was a result of “decades-long underinvestment in education.”

“We are calling for the increase in budget for education, at least 6% of the GDP,” she said. Currently, the Philippine government is only allotting 3% of its GDP for the education sector, lower than the global standard of 6%.

But for Alfonso, teaching students the importance of history should not stop in schools. He said that it should be “a whole of government approach” because students are dealing with different environments outside of their schools.

“It’s the duty of DepEd to teach students while they’re in school, and it’s the duty of the government to teach them outside school. It’s a whole of government approach. It should be a community approach. Media should also play a role by providing a wide variety of options for students to watch,” he said in a mix of English and Filipino.

The ways forward mentioned above were just some of the items in the 10-point agenda that Education Nation – a coalition of 35 organizations and 21 experts – was recommending to the public as their criteria in choosing the right candidate for what they called “Education President.”

In a press briefing on Monday, April 25, Education Nation revealed that it was Vice President Leni Robredo who got 10/10 in their 10-point agenda. They said that “Robredo is the leader that can solve our learning crisis.” (READ: ‘Education president’: Experts score Robredo 10/10 for her education platforms)

A number of education groups, including schools and former education officials, have endorsed Robredo’s candidacy for president. In 2021, Robredo called on the government to declare a “learning crisis” in the Philippines following a World Bank report on poor learning results among Filipino students. (READ: DepEd head demands apology from World Bank for PH poor education ranking)

As the elections draw near, Education Nation encourages the public to vote for a president “with a detailed strategy to take us out of this mess.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.