SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Editor’s Note: In this 3-part series, a Rappler investigative team scrutinized the first batch of files submitted in June 2018 by the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) to the Supreme Court. Consisting of police reports, the documents were supposed to provide insight into the regularity of police operations in President Rodrigo Duterte’s violent campaign against illegal drugs. Part 1 discusses the quality of the files submitted by the OSG, tracks the progress of the case at the SC, and spells out what their implications are.

At a glance:

- After the Supreme Court ordered the Duterte government to submit documents on drug-related killings, it took two years before petitioners got a complete copy of the files for their own analysis.

- One of the petitioners had to file a motion for contempt against the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) before Solicitor General Jose Calida submitted a second, and supposedly correct, batch of files.

- Petitioners still have difficulty extracting relevant data from the second submission of the OSG.

The constitutionality of President Rodrigo Duterte’s war on drugs is under litigation in the Supreme Court (SC), but for the last 4 years the case has been stalled by the government’s submission of what petitioners describe as “rubbish” files on deaths in the anti-drug campaign, Rappler’s investigation shows.

Rappler obtained a copy of the first batch of folders submitted on June 25, 2018, to the SC by the Philippine National Police (PNP) through the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG). The submissions, we discovered, had as many as 165,454 individual files contained in 291 folders that, in turn, covered at least 55 provinces.

Our team combed through the over 160,000 individual files for a year and found that the folders were redundant, included cases not relevant to the drug war, and excluded so many other cases that had been previously documented and reported on by the media.

Ray Paolo Santiago, executive director of the Ateneo Human Rights Center (AHRC), said that, beyond the sloppy documentation of deaths in drug operations, “it is really disappointing and alarming how trivially the respondents in the case are taking the orders of the Supreme Court and the subject matter of the case itself.”

The submitted documents were supposed to allow the SC to verify if indeed police anti-drug operations were properly planned and conducted, and whether they were regular operations.

The submissions did not allow such an assessment. Yet, earlier, the SC said that a “genuine judicial review into the constitutionality” of the drug war “must logically start with the police reports.”

The documents would help the Court assess the regularity of the flagship campaign of the Duterte administration which is widely criticized for being bloody and violent.

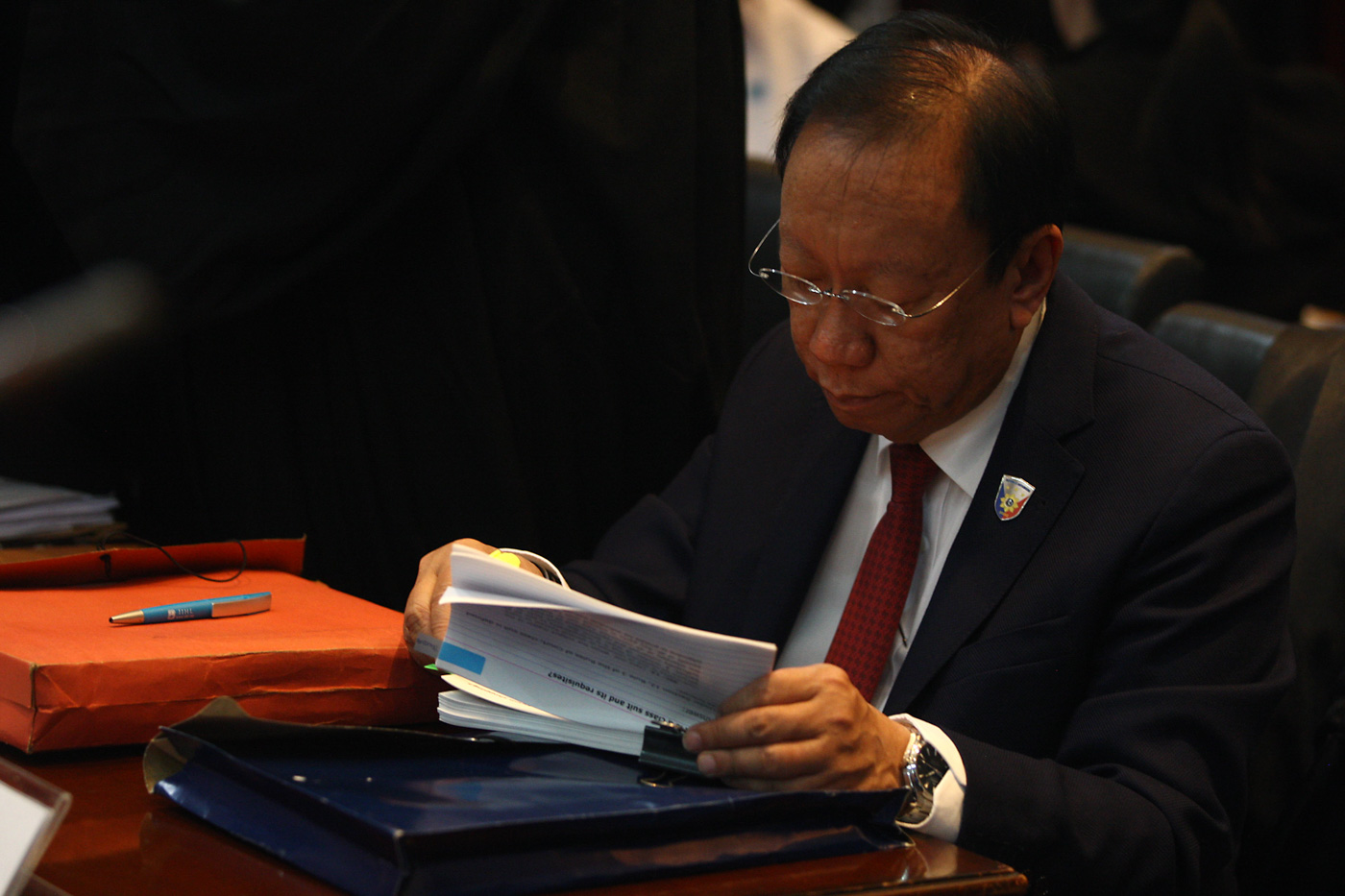

Solicitor General Jose Calida had resisted complying with the directives of the SC, buying as much time as he could, invoking national security. Over a period of 4 months – between December 2017 and April 2018 – he filed 3 motions for reconsideration, extension, and opposition. He grudgingly submitted the required documents only in June 2018 after his motions were denied by the High Court.

He had also initially refused to provide petitioners that included the Center for International Law (CenterLaw) and the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG) copies of his submissions, arguing that the reports should not be given to other parties uninvolved in the cases.

This process required Calida to file 3 more motions for reconsideration and extension from September 2018 to October 2019. It took 8 months for the petitioners to get their copies from the time the SC granted the first request in August 2018.

‘Rubbish’

When Calida finally provided copies of his submissions in September 2019, petitioner CenterLaw described the OSG submission to the High Court, at least 209 gigabytes in size, as “rubbish.”

The practically useless data prompted CenterLaw to file a motion for contempt against the OSG in September 2019, saying, “The misrepresentation on and submission of irrelevant documents to the Supreme Court by the OSG and PNP constitute direct contempt of court.”

For instance, the bulk of files on Metro Manila, the known center of the killings during the timeframe specified by the Supreme Court (July 1, 2016, to November 27, 2017) were not included in the first batch of submissions. Only 3 hot spots – Bulacan, Davao City, and Negros Occidental – were part of the police investigation reports.

In the OSG’s submission, files were disorganized, with the same provinces scattered in different volumes placed in different folders. Rappler learned that the drug war folders were collated by local police stations, forwarded to their provincial offices, which, in turn, forwarded them to their regional offices. From there, the data was delivered to the PNP national headquarters in Camp Crame. It was the OSG that finally submitted the documents to the Supreme Court.

Rappler asked the OSG for comment on this story in messages sent on February 8, 18, 19, and 22. OSG spokesperson Hector Calilung told Rappler in a message on February 22 that he was still waiting for instructions. We will update this story once we hear from him.

It will be recalled that during oral arguments in December 2017, then-senior associate justice Antonio Carpio, the member-in-charge of the case, ordered Calida, “I want the names, addresses, and all the reports regarding these 3,806 killed in legitimate drug operations.”

Months later, on April 3, 2018, the SC issued a resolution that said documents related to 20,322 killings linked to policemen and vigilantes from July 1, 2016, to November 27, 2017, should be submitted to the Court.

Calida’s defense

When the SC asked the OSG to comment on the motion, Calida claimed in a November 25, 2019 pleading – almost two years since the SC’s first order – that there was just some confusion over police terms. The OSG said that while the High Court had been using the term “deaths under investigation (DUI)” in relation to the drug war, the police understood it to mean all deaths under investigation, regardless of the motive.

Calida claimed in the same pleading that when his office communicated the SC’s order to the PNP, they explained that what the Court wanted were drug war files. It was clear, after all, from Carpio’s directive in December 2017 that the SC was interested in reports pertaining to the drug war.

To corroborate Calida’s claim, Rappler sought the comment of the national headquarters, requesting an interview on February 1 via a text message sent to Major General Marni Marcos, chief of the Directorate for Investigation and Detective Management (DIDM). He has yet to reply as of posting.

Ateneo Human Rights Center’s Santiago said the “honest mistake could have been addressed by proper coordination by the agencies and officers involved. Sadly, the mistake has shown the lack of this.”

OSG’s second submission

Calida submitted a second batch of files, which the Supreme Court received in November 2019, court records showed. Sources privy to the information said even the additional files submitted were corrupted and, like the first submission, practically useless.

CenterLaw president Joel Butuyan told Rappler on February 8 that they were still in the process of analyzing the second batch, as they were delayed by the coronavirus pandemic. Rappler has yet to access these files.

But in a pleading in February 2020, CenterLaw said of the second submission: “On November 29, 2019, after the stonewalling machinations, respondents furnished the petitioners the documents purportedly in compliance with the directives of the Honorable Court. It turns out, however, that the documents indeed included numerous non-drug related incidents.”

FLAG chairperson Jose Manuel “Chel” Diokno told Rappler on February 17 that “there was no relevant data that we could extract from the second batch,” adding that “there were a lot of irrelevant material.”

Diokno said they still have a pending motion to be furnished with “legible copies of the files from the first batch.”

The SC’s Public Information Office (PIO) confirmed to Rappler on February 22 that the justices last took action on this case way back on March 3, 2020 – almost a year ago. They merely took note of CenterLaw’s manifestation that the police operations in their clients’ community in San Andres Bukid in Manila, where 33 people were killed, were “illegitimate” and “violently conducted.”

The delay in the submission of files and police reports, which will make it difficult for the SC to decide on the constitutionality of the drug war, can boost the case against President Rodrigo Duterte at the International Criminal Court (ICC), said Santiago of the Ateneo Human Rights Center.

The ICC Office of the Prosecutor will decide by first half of 2021 whether or not to open a formal investigation. To do this, the office needs to determine that the Philippine justice system has been unwilling or unable to prosecute the killings under Duterte’s war on drugs.

As of December 2018, human rights organizations had pegged the number of deaths in the drug war at over 27,000. In contrast, the PNP placed the number of drug suspects killed as of May 2019 at only about 6,600. (READ: Duterte gov’t allows ‘drug war’ deaths to go unsolved)

In December 2020, ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said there was “reasonable basis” to believe that crimes against humanity were committed in the drug war killings.

Santiago said, “If the documentation is utterly lacking, then we cannot expect any accountability for any transgression. There is a failure then to bring about justice.”

“And if this modus operandi is shown to be widespread and systematic, as mentioned by the Office of the Prosecutor of the ICC in its most recent report, then it builds a case for the ICC to take jurisdiction,” Santiago added. (To be continued: Part 2 | Incomplete submissions show a poorly documented drug war)

– Rappler.com

This investigative series was put together by Rappler’s crime and justice cluster, composed of Lian Buan, Rambo Talabong, Jodesz Gavilan, Michelle Abad, and Pauline Macaraeg. Michael Bueza contributed to the visualization of data.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Vantage Point] China’s silent invasion of the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-china-silent-invasion-july-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.