SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] PAREX: Sacrificing urban vitality for a traffic ‘solution’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/07/parex-urban-vitality-sq.jpg)

One promise is a timeframe of 15 to 20 minutes across cities in Metro Manila. Another is “better, more efficient, more comfortable, and pleasant cities interconnected by sustainable infrastructure.”

PolitiKomiks, in its viral post, rightly refutes this: “Skyways are not the answer.” In their cross-sectional illustration of an elevated road, a shadow is cast on the real city: those who can afford private cars and pay for tolls loom over the commuters on bikes and on public transport who need better, inclusive mobility across the metro.

‘Sacking’ our urban environment

The construction of monumental infrastructure is highly reminiscent of a classic story known to urbanists, about the battle between Jane Jacobs, an activist, mother, and writer, and Robert Moses, a titan masterplanner and power broker.

Please indulge us in this brief retelling: Moses, who had amassed power through the construction of expressways, parks, and residential buildings in New York, planned the construction of bridges and roadways, including the Lower Manhattan Expressway, that would render places uninhabitable in the guise of “urban renewal.” Jacobs opposed the demolition and bulldozing that threatened dense communities by organizing rallies, appearing in hearings, and leading grassroots movements. In her 1961 book which criticized modernism and influenced new urbanism, she wrote, “But look what we have built…. Expressways that eviscerate great cities. This is not the rebuilding of cities. This is the sacking of cities.”

The expressway proposal was eventually dropped. Today, cities around the world work for highway removals, urban transformation for 15-minute cities or humane places, efficient public transportation, and pedestrian infrastructure.

The Philippines, then, chooses to regress when it prioritizes car-centric planning.

Bypassing the public city

A permanent shadow on the city is one of many horrors that come with these new elevated roads. Induced demand can worsen congestion; city, landscape, and river character can be destroyed; and urban inequalities can worsen. Infrastructure that encourages more cars in the city, and that increases greenhouse gas emissions despite greenwashing tactics, is far from sustainable.

Advocates have been vocal about these projects that are billed as “developmental,” but which really build, build, and build business. “People over cars,” they repeatedly clamor, critical of how branding a project with “livable city” principles does not really address the needs of communities. For one, many cannot afford the expensive toll every day.

But aside from desiring inclusive urban design and mobility, understanding the system behind grand infrastructure is important. These megaprojects are a result of “bypass-implant urbanism,” where elite developers in the country continue to privatize spaces for capital accumulation. Building roads to and from spaces of production and consumption (e.g. malls and condominiums) bypasses the rest of the real city.

Let’s take PAREX as an example. Planners ask about its necessity: How much of the Pasig River, its social benefits, and its heritage will be “sacrificed?” Will building an expressway address the fragmented suburbs and the informal areas and streets which make up Metro Manila?

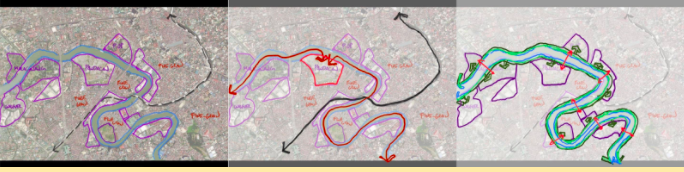

This series of sketches, which analyzes the project’s urban environment, prompts reflection on how we should address what already exists; what is proposed is “an urbanism that implants new connections that expand the narrow public realm of the river banks” to “implant new, fine-grained connectivity that helps suit the scale of the urban context, and connect these parcels to their surroundings.”

Regenerating cities through its waterfronts

Progressive cities around the world are transforming their waterways, utilizing blue-green network strategies and regenerative development principles. This is manifested through participatory planning processes that lead to the creation of high quality spaces with a strong sense of identity, characterized by a spacious public realm, buildings that have a physical and visual connection with its waterfront, and the restoration of watercourses into a more natural state. Well-known examples include the demolition of inner city highways in favor of these spaces, such as the Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul and the Madrid Rio project, both of which pioneered this movement in the mid-2000s.

In Metro Manila, endeavors to rehabilitate Manila Bay and the esteros of Manila demonstrate an effort to restore these treasured waterfront assets. An unmissable opportunity to realize these desired outcomes exists through the emerging “C5 mixed-use development corridor,” with its large land holdings and expansive river frontage. But this can only happen if there is a strong political will to secure net benefits for the community and the environment, along with concerted planning efforts between agencies and developers.

Imagine the possibility of a future wherein our transport options are not limited to cars – residents from as far as Marikina being able to commute all the way to Makati or Manila through a metropolitan-wide cycling trail along the riverbanks, complemented by an expanded Pasig River Ferry service.

While these outcomes can still be feasible with the proposed PAREX viaduct directly adjacent, its massive structure will undoubtedly cause visual intrusion to the Pasig River’s landscape. And if aesthetic impact is not a concern, consider the degenerative impacts to the river environs’ amenity: loss of access to sunlight, an amplified urban heat island effect, and an increase in direct stormwater discharge to the river and in noise and air pollution. Undeniably, if the expressway gets built, the river’s landscape will be radically transformed and the sense of place and identity that Filipinos historically associate with it will be harder to recover.

Whole-of-river planning: Nurturing community and urban vitality

So how can we better approach planning? Let us learn from a precedent. Recognizing the river as a living entity and acknowledging the distinct landscape character, environmental values, and issues occurring at its different sections (rural, suburban, and inner city reaches) is what characterizes the whole-of-river planning approach for the Yarra River in Australia, the first of its kind. A coordination of planning frameworks between agencies and local government units that have jurisdiction over the river, anchored on a strong community vision, enables them to achieve consistent and far-reaching sustainable outcomes for the whole river. The community vision speaks of the river’s significance for heritage, for the natural environment, and as an iconic symbol of the city – on hearing these, be reminded of what is at risk to be lost when excessive development is permitted.

Inappropriate development and activities upstream have a major ripple effect downstream of the river, and on to bays and oceans. The urban vitality and environmental quality of the Pasig River’s estero communities have suffered for a long time, being at its downstream end. Rehabilitation activities in recent years have achieved significant environmental and social gains, inspiring optimism for the revival of these places, but despite these wins, it should not be forgotten that they can be easily nullified if inaction from stakeholders in other reaches of the river persists, affirming the need for a whole-of-river planning approach to be considered.

Hopefully, with all these in mind, we can begin to develop nuances to the “solutions” promised to us. Is another expressway really helping our cities progress? Are more elevated roads the solution? What will be the future of our urban landscape be if we continue to excessively build? – Rappler.com

Ragene Palma studied MA International Planning and Sustainable Development at the University of Westminster as a Chevening scholar. April Valle obtained her Master of Urban Planning degree from the University of Melbourne and is a member of the Planning Institute of Australia. Both authors are urbanists.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] Why we can’t Build, Build, Build our way out of this pandemic](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/07/tl-build-build-build-coronavirus-may-14-2020_537E7FB2F6FD4E02AF6B531AE8F23C22.jpg?fit=449%2C360)

![[EDITORIAL] Kamaynilaan para sa tao, hindi para sa mga sasakyan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/animated-traffic-april-2024-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=410px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[ANALYSIS] Investigating government’s engagement with the private sector in infrastructure](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-gov-private-sectors-infra-04112024-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] Cities and public spaces should be for people first](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/imho-people-first-city-04132024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.