SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Triple whammy: Why are prices rising so fast?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/9771578EEA9E462A9AD64658C7AE1452/high-prices-20180207.jpg)

On February 6, the government announced that the country’s “inflation rate” – which measures how fast prices are rising – reached 4% in January 2018, its highest level in more than 3 years.

While government officials and private sector economists projected inflation to pick up this year, nobody expected it to be this fast: January’s 4% exceeded everyone’s expectations.

In this article we try to explain the causes of this surprise uptick. Many blame the new tax reform law called TRAIN. But it’s more likely caused by a triple whammy of profiteering, higher oil prices, and the peso’s weakness.

Beyond expectations

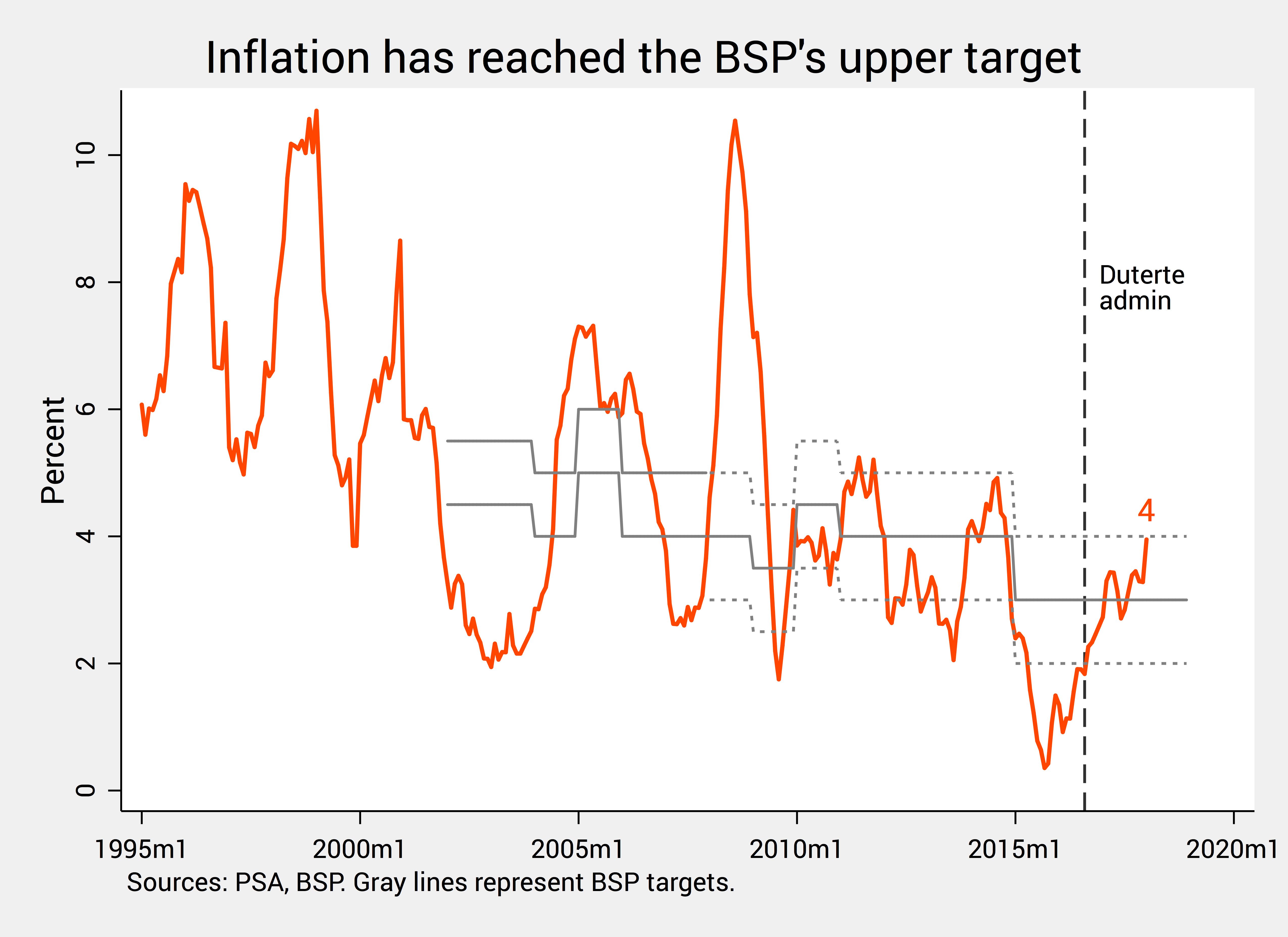

Figure 1 shows the historical trend of the country’s inflation rate. Inflation is “too high” or “too low” depending on how it compares with the Bangko Sentral’s targets. For 2016 to 2018, the Bangko Sentral targeted an inflation rate between 2% and 4%.

Note that when President Rodrigo Duterte came into office, we were at the floor of this range (2%). Today, just 19 months later, we’ve reached the ceiling (4%).

Figure 1.

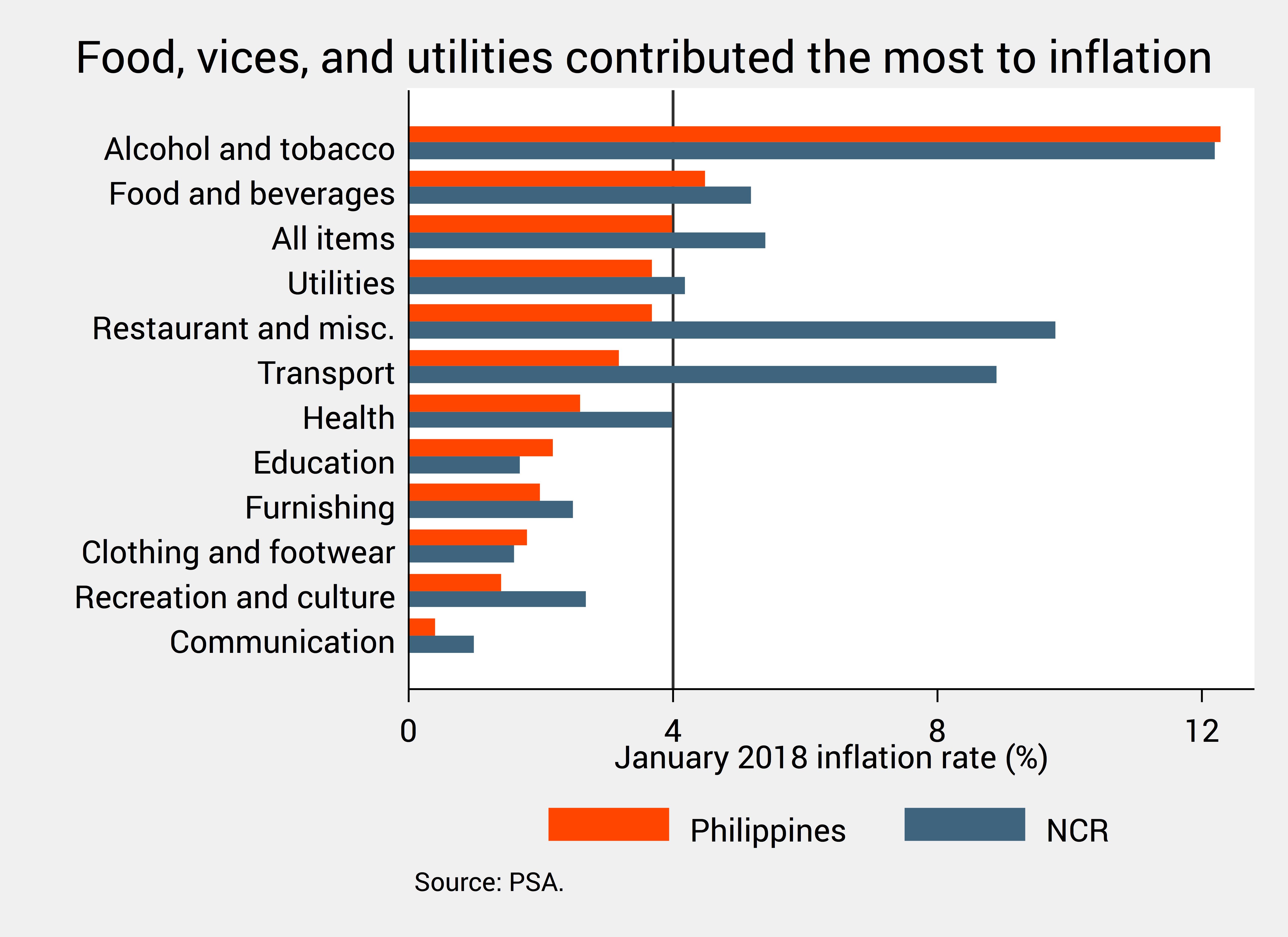

Which commodities saw the fastest rise of prices in January, and where? Although media outfits usually report just one inflation figure, there are actually several inflation figures across different commodity groups and regions.

Figure 2 shows that the prices of alcohol and tobacco products rose fastest (at 12.3% or more than 3 times the overall inflation rate). This is followed by food and beverages (4.5%), utilities like water and electricity (3.7%), and restaurant meals and miscellany (3.7%).

Meanwhile, at 5.4%, the inflation rate for NCR was higher than the national figure. Alcohol and tobacco prices also rose the most here (12.2%), followed by restaurant meals and miscellany (9.8%), and transportation (8.9%).

Figure 2. Note: I put a line on the 4% level to mark the overall inflation rate.

But we don’t consume goods and services equally. If we take into account the relative importance of the commodity groups, data show that food and beverages accounted for 50% of the increase in January, utilities 19%, and restaurant meals and miscellany 10%.

Triple whammy

What caused this spike in inflation? Many blame TRAIN, which took effect on January 1.

But TRAIN’s new taxes can’t explain all of it. Sure, the tax on sugar-sweetened beverages might explain the huge contribution of food inflation. But TRAIN also included but a modest increase in the excise tax for cigarettes (from P30 to P32 per pack). Alcohol taxes weren’t even touched in TRAIN. So TRAIN alone can’t explain the double-digit inflation of alcohol and tobacco prices.

Instead, the inflation spike was likely borne by the combined effects of profiteering, higher world oil prices, and the peso’s depreciation – a veritable triple whammy.

First, TRAIN’s new taxes took effect on January 1, but sellers can apply them only to new stocks of goods, not old ones.

Many sellers reportedly cheated on this policy and engaged in illegal profiteering. Energy regulators, for instance, were on the lookout for gas stations that prematurely raised their gas and diesel prices. (READ: DOE to gas stations: Don’t take advantage of tax reform law)

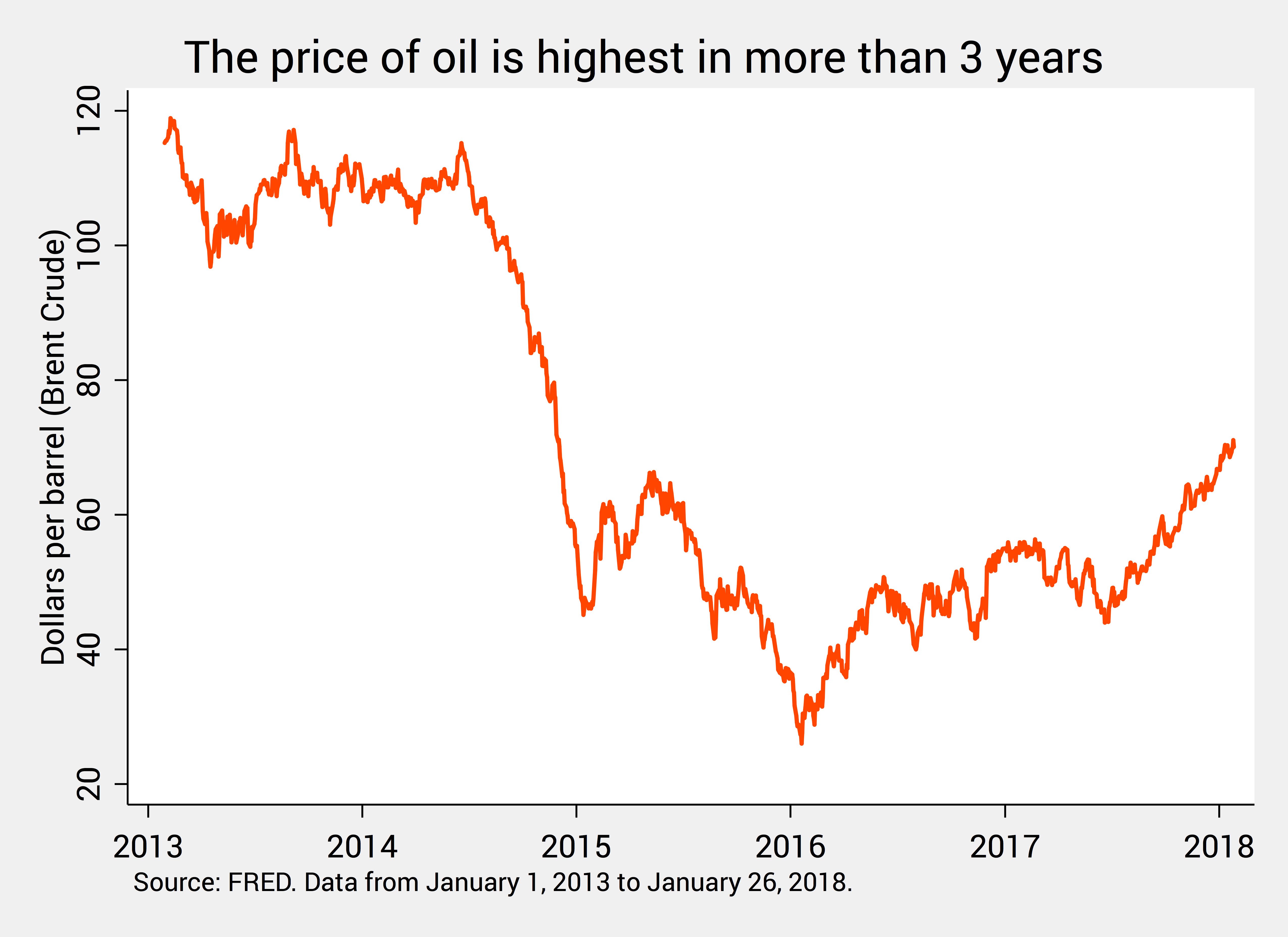

Second, on top of TRAIN’s new excise taxes, petroleum products are becoming more expensive in the world market.

Figure 3 shows that the world price of oil is reaching record highs. In late January, the price of “Brent Crude” – a benchmark kind of crude oil – reached $70 per barrel, the highest in more than 3 years.

Figure 3.

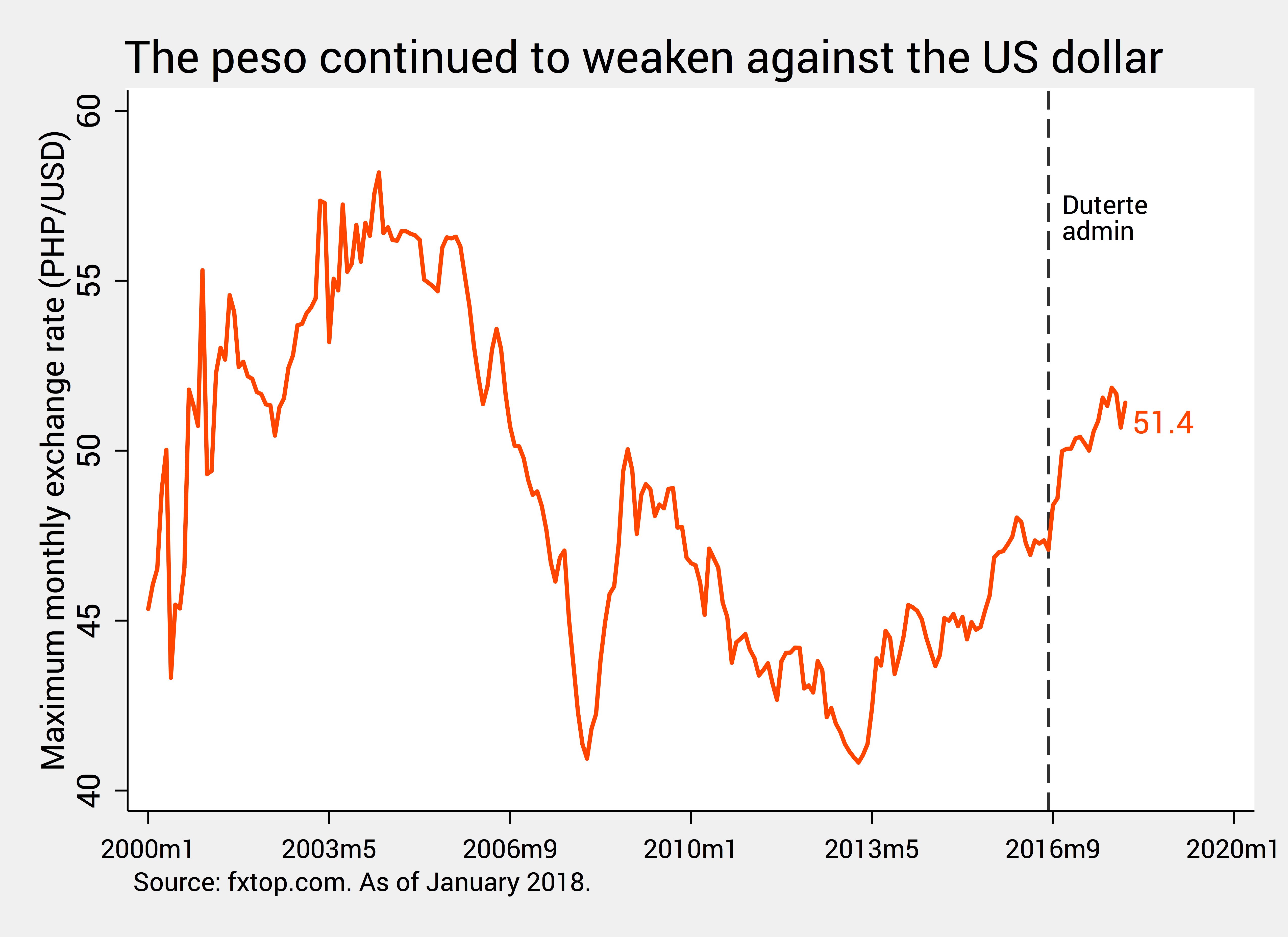

Third, the peso’s continued weakening is making imported products even pricier. Figure 4 shows that in January the peso settled around P51 per US dollar, a continuation of the peso’s long-term depreciation since mid-2013.

When the peso weakens (say, from P47 to P51 per dollar) we have to pay more pesos for the same imported product. This partly explains why gasoline prices, for instance, now range from P50 to P52 per liter.

Since petroleum products are used throughout the economy, a weaker peso spells costlier production across many industries, thus contributing to overall inflation.

Figure 4.

In sum, we haven’t yet seen the full effects of TRAIN’s new taxes. Instead, what we saw in January was likely a combination of profiteering, higher world oil prices, and the peso’s depreciation.

What’s next?

Throughout 2018, this triple whammy might persist.

First, profiteering is likely to continue unless the government dedicates a chunk of its resources to go after profiteers. In a recent Senate hearing, an assistant secretary of the Department of Energy admitted there is no mechanism in place to monitor and prevent abuse in all gas retailers.

Second, oil will likely become even more expensive this year, owing to strong global demand and OPEC’s decision back in November to cut its production throughout 2018. Brisk oil production in the US, however, might counter this.

Third, the peso is expected to weaken further against the dollar, on expectations that the US Federal Reserve will raise its interest rates 3 to 4 times this year to stem the US economy’s renewed growth. When it does so, it will attract investments from the Philippines, flood our market with pesos, and lower the peso’s value relative to the dollar.

On top of this, we will witness the full effects of TRAIN in the coming months, adding to the inflationary impact of the triple whammy.

What can we do? Our best hope in these tough times is the Bangko Sentral. Its primary role in economic policy, after all, is to keep inflation in check.

With the January figure already hitting its upper target for the entire year, the BSP is likely to rein in inflation by raising interest rates throughout the year. Some economists expect this to happen as early as Thursday, February 8.

Not the best time for TRAIN

It’s easy to blame TRAIN’s new taxes for the fast rise of prices seen in January.

But we really haven’t seen its full effects yet. Instead, the surprise inflation uptick is likely due to a triple whammy of profiteering, higher world oil prices, and the peso’s weakening.

In all this, one can’t help but think that TRAIN’s timing seems to be off. It would have been better to enact the tax reform law when world oil prices are falling rather than rising, or when the peso is strengthening rather than weakening.

Truth to tell, TRAIN’s passage was partly motivated by President Duterte’s immense popularity. Tax reform is contentious and divisive by nature, and TRAIN’s proponents hoped that a popular leader like Duterte would make it more palatable to the masses, and thus easier to pass.

But is Duterte popular enough to withstand the increasingly manifest costs of TRAIN? – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.