SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[In This Economy] Peso approaches P60 per dollar once more. So what?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/TL-peso-dollar-economy-may-24-2024.jpg)

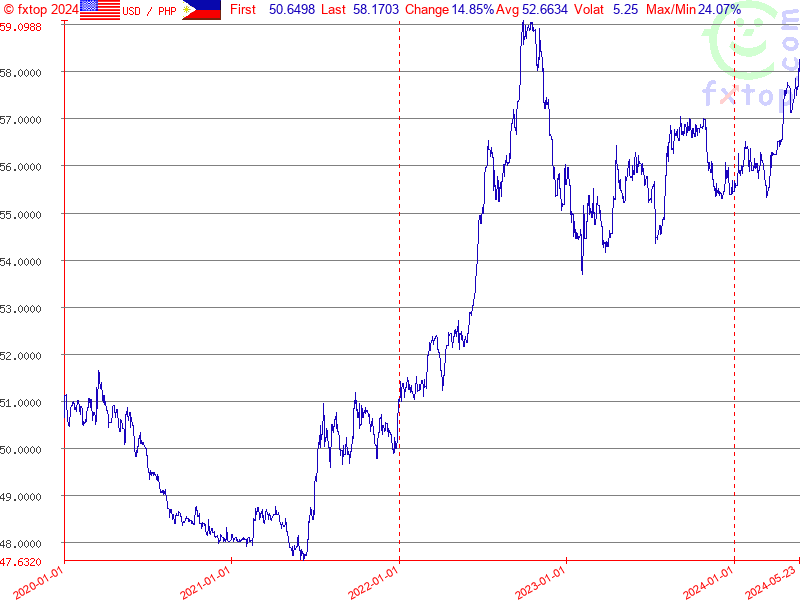

Once more we find ourselves with a weak peso that approaches the never-before-reached level of P60 per US dollar.

On May 21, the exchange rate breached P58 per dollar. If this trend continues, we might soon breach P59 per dollar, which we last reached in September and October 2022.

Source: fxtop.com.

Why is the peso getting weaker again? Who wins and loses from this?

In late April, Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) Governor Eli Remolona explained that “the story has been one of dollar strength rather than peso weakness.”

He elaborated, “Escalating tensions in the Middle East led to safe-haven flows into the US dollar at the expense of most other currencies. Nonetheless, the BSP continues to monitor the market and stands ready to manage any unnecessary movement and excessive volatility.”

What this basically means is that increasing uncertainties worldwide are pushing investors to put their money in dollar assets, which are safer than if they invest elsewhere (whatever happens the US can always print dollars).

Filipino investors wishing to avoid unnecessary risks will want to transfer their money to the US. But they need dollars for that. This increases the demand for dollars, which become scarcer relative to the peso. In turn, this drives down the price of the peso relative to the dollar.

In sum, a steady outflow of investments results in a weaker peso (or peso depreciation). This stems from basic supply and demand.

What will the BSP do?

Of course there’s nothing particularly earth-shattering about reaching P60 per dollar, except that we have never seen that level ever. It’s a psychological threshold, more than anything.

But if it wants to, the BSP can take steps to make sure we don’t reach that level.

It can do so by dipping in the country’s supply of dollars (or international reserves) and selling dollars to the market. By flooding the market with dollars, the BSP brings down the value of the dollar relative to the peso. The peso strengthens, and we will avoid P60 per dollar.

Recall that in 2022, former BSP governor Benjamin Diokno drew a line in the sand and committed never to reach P60 per dollar. The BSP then spent tens of billions of dollars to defend or prop up the peso.

The question now is whether the BSP will again tap our foreign reserves to defend the peso once more.

Already, Governor Remolona disclosed that the BSP has been injecting the market with dollars “in small amounts.” At the same time, he gave assurances that despite these measures we’re nowhere near running out of international reserves. We have more than enough supply of dollars.

The last thing we want, though, is to spend inordinate quantities of dollars for the sole purpose of not reaching P60 per dollar. So doing nothing is also a feasible option.

If we let the peso slide further, imported goods will be a lot more expensive, and that can stoke domestic inflation – something that the BSP is finding difficult to tame further because rice (over which it has no control) has been contributing a lot to food inflation, and in turn, overall inflation.

Exchange rate volatility is the price paid by countries like the Philippines, which allow the free flow of capital across its borders and, at the same time allows the monetary authority (the BSP) to conduct independent monetary policies. You can’t have all good things in life, and the same applies to international finance.

Another implication of the weaker peso is that the BSP will take longer to bring down its policy interest rate, or the rate that orchestrates interest rates throughout the Philippine economy.

You see, there is pressure for the BSP to reduce its very high policy rate, which has stifled growth in borrowing and spending. After all, inflation is now (technically) within the target range of 2-4% (in April, it was 3.8%), and high rates are designed precisely to bring down inflation.

If the BSP yields and lowers its interest rates soon, this will widen the gap between interest rates here and in the US, and even more investors will choose to put their money in the US. This will trigger even more capital outflows, and an even weaker peso.

But if it holds on to high interest rates, that will limit the extent of spending growth in the economy. Growth might suffer.

So you see, managing the economy is full of trade-offs, and the work of policymakers like BSP officials is far from easy. Any decision they make will have massive implications on the economy, creating winners and losers. And the trick is to pursue the best policy that will benefit most Filipinos.

This is one of the reasons why BSP officials are among the highest-paid in government!

Fake news

Speaking of the BSP’s functions in our society, I’m reminded of the gathering of hundreds of people in front of the BSP Complex recently.

A certain Gilbert Langres, founder of Democratic and Republican Guardians Philippines Inc., egged people to troop to the BSP which is supposedly hiding a public fund amounting to P19.5 trillion (almost as large as the inflation-adjusted GDP of the Philippines in 2023). Parts of that money were supposed to be handed out by the BSP that day.

But as explained by the BSP itself, “it does not directly distribute money to the people,” and instead “provides a dividend to the government to contribute to programs that can improve the livelihood of Filipinos.”

On the BSP website, too, their mission is clear: “To promote and maintain price stability, a strong financial system, and a safe and efficient payments and settlements system conducive to a sustainable and inclusive growth of the economy.” There’s no secret fund, let alone any obligation to distribute such secret fund.

This incident is at once humorous and sad. Humorous that so many would believe such an absurd lie (as absurd as the Tallano gold myth that went viral before the 2022 polls).

Sad because so many people believe such claims and don’t see them as absurd. They genuinely believe such myths.

Obviously, we still have a long way to go where financial and economic literacy is concerned. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan, PhD is an assistant professor at the UP School of Economics and the author of False Nostalgia: The Marcos “Golden Age” Myths and How to Debunk Them. In 2024, he was given The Outstanding Young Men (TOYM) Award for economics. JC’s views are independent of his affiliations. Follow him on Twitter/X (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ Podcast.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

It’s not just the high salaries that raise eyebrows. The top officials of BSP are the highest-paid in the government, even more than the President. This begs the question-why? Could it be that the President’s understanding of the policymaking work of BSP officials is limited? Or is it a strategy to ensure immediate compliance with the President’s policies? Policies that, it seems, are more likely to favor the President’s campaign fund donors, family members, and relatives doing business than the Filipino people.