SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

“It doesn’t matter how and when it happened. Sister, you are not alone.”

This motto has gained relevance on the Cuban stage with the recent creation of #MeToo Cuba, an independent project carried by women and LGBTIQ+ victims, survivors, and denouncers of sexual violence on the island.

“Being aware that wherever there was a victim of sexual violence accompanied by someone, there was a #MeToo, a safe space is born today…in the absence of institutional support”, said their first statement published on their social media.

The rise of the platform is linked to the fanning of the international #MeToo movement’s flames after the new accusations of sexual violence against the French actor Gérard Depardieu and the Portuguese sociologist Boaventura de Sousa Santos, two figures who have been linked to the upper ranks of power and cultural institutions in Cuba.

“We work on sexual education with two purposes: the prevention and the possibility for survivors to recognize, to name the violent experiences they have lived through…. This includes both cis women and members of the LGBTIQ+ community, and even cis-straight men,” the collective told elTOQUE.

“We want to create a community that can support them in a tailored way and also in groups, depending on their needs, in alliance with other organizations, such as the YoSíTeCreo platform in Cuba, plus the experience of other survivors,” they added.

#MeToo Cuba focuses on sexual violence. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines sexual violence as “any sexual act, attempt to commit a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or actions to market or otherwise use a person’s sexuality through coercion by another person, regardless of that person’s relationship to the victim.”

In this sense, #MeToo Cuba is strengthening support networks, making it easier to carry out a public denouncement or legal lawsuit. “A shoulder, a vital ‘I do believe you,’ that overpowers the ‘You were asking for it’ and its variants in patriarchal societies like Cuba,” they explained.

The platform’s work is also linked to journalists and the media for the followup on reports, testimonies, and specialized articles on sexual violence, as well as with lawyers. Among the collective’s priorities is opening up the path to restorative justice, including a public debate that impacts both Cuban society and the state.

While the #MeToo movement worldwide is known for its public exposure, this is not the main objective of the Cuban space. The support they offer is on demand, punctual, as the verb “to accompany” indicates.

“We want to create a history of #MeToo worldwide and #MeToo in Cuba, our own memory as a way to feel less alone,” they said. “We want to prevent sexual violence with sexual education.”

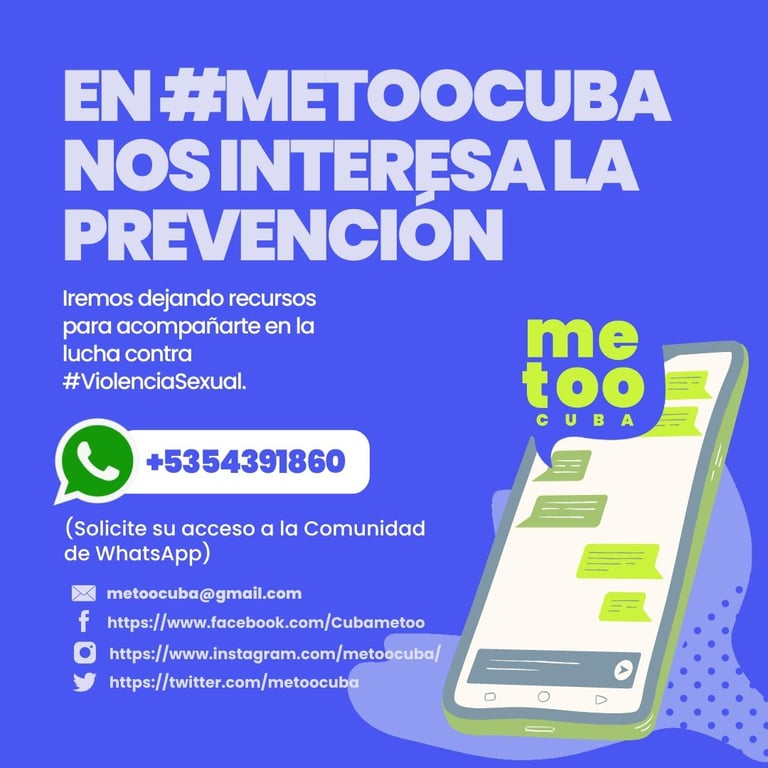

On how it works, they pointed out that “there are several communities being set up…. We have organized the network through WhatsApp because it is a safe network. The groups are set up according to interests, specifics, and only for survivors. No information will be taken from these spaces to be published unless it is a demand made by the survivor.”

Sexual violence has many faces, from verbal harassment to rape, from psychological oppression to the use of physical force. It can happen at any time and in any place: at home, at work, or on the street. It is an act of power in which the victims are mostly women, gender-diverse, underaged, and feminized bodies.

When #MeToo took the world by storm

The global wave of #MeToo – Yo También in Spanish – as an articulated movement began in October 2017. Journalists Jodi Kantor and Mega Twohey published an article in The New York Times exposing decades of sexual assault by Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein. Weinstein, a producer of countless Oscar-winning and blockbuster films, was considered untouchable.

The now iconic phrase coined years earlier (in 2006) by African-American human rights activist Tarana Burke was popularized by actress Alyssa Milano. Through her social media, the actress encouraged other women to speak out and report their experiences of abuse. Burke had begun to use the expression not as a healing tool, but with an empathetic connotation towards victims of sexual violence – especially in marginalized communities. The original goal behind #MeToo was to start a small conversation and create a community among survivors.

However, the tweet set off an explosive wave. The hashtag was used more than half a million times in a single day and trended in more than 85 countries, with spontaneous versions in many other languages.

When the movement burst onto the networks, the Ni Una Menos movement (2015) had been gaining momentum in Latin America for some years in protest against the chilling figures of femicides. Latin America has the highest rate of sexual assaults against women globally. The slogan – accompanied by diverse popular mobilizations – originated in Argentina and spread on a large scale to other countries on the continent. It gained momentum in 2017 with the Weinstein case, the fight for the legalization of abortion in mid-2018, and Thelma Fardin’s accusation against her former co-star Juan Darthés at the end of that year.

The #MeToo movement provided a platform for survivors around the world to share their stories and feel supported. The movement pushed for the enactment of laws and public policies aimed at preventing sexual violence and protecting survivors. It also reduced the sense of impunity by at least making it easier to publicly denounce perpetrators and challenged societal tolerance of harassment and other sexual violence.

Many of these stories are replicated in #MeToo Cuba networks and spaces to connect the island with the global movement.

Faces of gender-based violence in Cuba and citizens’ initiatives

In Cuba we did not have Weinstein, Darthés, or Cosby, but sexual and gender-based violence had other names and other struggles.

One of the first popular cases on the island was that of the writer and political activist Ángel Santiesteban Prats, sentenced in February 2013 to five years imprisonment for the crimes of assault and housebreaking. Santiesteban was denounced in 2009 by his ex-wife and mother of his children Kenia Rodríguez for physical and sexual violence.

The criminal proceedings took three years. Once the conviction was made public, there were several reactions in support of the writer and against the court’s sentence. Santiesteban’s critical stance against Cuban government officials led many to call the trial “controversial” or to consider it a “political prosecution” in disguise. Among them was the writer Rafael Alcides, who, in a text entitled “Lamentaciones y esperanzas por un nuevo escritor encarcelado” (“Regrets and hopes for a new imprisoned writer”), described the events denounced as a “simple quarrel.” A “drama of a folkloric nature that is usually so amusing,” said the letter of support.

Alcides’ words were responded to with a missive launched on International Women’s Day (March 8, 2013) which, as the days went by, was read out at the headquarters of the Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba (Uneac). In it, the signatories – women artists, communicators, and intellectuals – opposed the accusations made against Kenya and claimed that the ideological stance of the aggressor distorted the magnitude of his violence, “the only reason he has been condemned.”

Santiesteban was released on parole in 2015, having served only two and a half years of his sentence.

Almost six years went by since Santiesteban’s sentence when, on June 14, 2019, Cuban influencer Alex Otaola asked Dianelys Alfonso, “La Diosa,” live, about the beatings and rapes perpetrated by José Luis “El Tosco” Cortés during the time she was a member of NG La Banda.

La Diosa’s response was accompanied by a rapid process of delegitimization, personal criticism, and insults. In response, a movement of support and solidarity for the singer arose under the hashtag “YoSíTeCreo en Cuba,” the name of the first Cuban platform for the support and accompaniment of people in situations of male violence.

“It doesn’t matter who the victim is, whether a famous artist, an army colonel, or a political dissident. It doesn’t matter how much time has gone by since the episode of abuse. It doesn’t matter the sentimental-affective relationship between the victim and the abuser. Gender violence must be made visible, denounced, punished, and repaired. Victims of male violence need to be heard, supported, and protected,” said the Cuban Feminist Assembly in an open letter in June 2019.

YoSíTeCreo in Cuba was a fundamental pillar in the case of La Diosa and in the following support for other survivors. The platform also took up the debate on the imperative need for a comprehensive law against gender-based violence in the country and, in 2020, created a helpline for people affected by gender-based violence.

El Tosco – the king of Cuban timba, the master of the flute and Dianelys’ aggressor – died on April 18, 2022, without having been prosecuted and without any Cuban institution responding to the accusations.

In December 2021, the first five survivors’ testimonies against troubadour Fernando Bécquer were published in the independent magazine El Estornudo. As the weeks went by, other names were added, bringing the total number of complainants to almost 30.

Once again, women and feminized bodies took cyberspace by storm. The feminist agenda returned to the public agenda. This was evidenced by the circulation – almost immediately – of the so-called “Comprehensive strategy for the prevention of and attention to gender violence and violence in the family” and the lukewarm and terse statements on social networks by the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC) and the Cuban Institute of Music (ICM).

The musical troubadour was convicted of the crime of abuse against six women and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment in the first instance, as stipulated by the old 1987 Criminal Code, under which he was tried. No more than four months had passed since the initial ruling when the Havana Provincial Court announced that Bécquer would serve his sentence “in internal regime” following further acts of harassment.

In November 2022, a group of Cuban women accused the director of the Amadeo Roldán Conservatory in Havana, Enrique Rodríguez Toledo, of having sexual relations with teenage students. Testimonies collected by CiberCuba tell how, for almost three decades, the teacher abused his position of power to harass and violate his students. He harassed, raped, and humiliated them. Survivors claim that the abuses were known to the institution and the student body.

“Of course I saw all these things happening. Of course I also saw how some of my 16- or 17-year-old classmates were happy to be with Enriquito, because Enriquito had a house and lived alone. Because it was better to be with Enriquito than with the family that demanded so much. And Enriquito practiced the ‘Chinese’ energy and the ‘breathing’ and it was a good quantity. Until the day Enriquito stopped being good and the disaster began,” Amanda Toirac, who graduated from the Conservatory in 2013 as a pianist, wrote on Facebook.

Reports of sexual assaults inside Cuban prisons have also been made public, a systemic practice connected to political violence against dissidents. In an interview with Diario de Cuba, activist Yeilis Torres Cruz told how, on the third day of being held in the 100 y Aldabó prison, she was raped by two men who called themselves “Manguera” and “Mandarria.” The assailants were under the orders of a captain identified as Abel. The name reappeared in the testimony of Gabriela Zequeira Hernández, detained during the social unrest of July 11-12, 2021.

‘We want to stay alive’

Sexual violence is a reality in Cuba and is often socially accepted. The known cases – and those that do not make the headlines – allow us to affirm this. Sexual violence flourishes as soon as the social and structural conditions for it are created.

Yes, Cuba is a signatory to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), although it has not ratified the protocol. It did incorporate gender-based violence as an aggravating circumstance in the new Penal Code, in force since December 2022. It also has a comprehensive strategy for the prevention of and attention to gender-based violence and violence in the family and the National Programme for the Advancement of Women.

However, gender-based violence continues to be a social problem on the island and requires urgent attention – so much so that, at the beginning of 2023, feminists and independent civil society organizations demanded that the government declare a “state of emergency due to gender violence,” given the increase in femicides and disappearances of women and girls.

“They are killing us,” states the call published by the platform YoSíTeCreo. It describes the state of emergency as a necessary mechanism to “establish prevention measures and eradicate behaviors that promote gender violence, along with protection protocols for survivors.”

In recent years, repudiation of gender-based violence has been gaining ground in public debates. This is largely due to the efforts and articulation of independent citizen groups. Support networks, such as #MeToo Cuba, have been an indispensable aid for survivors of sexual and other types of gender-based violence. Initiatives that continue to advocate for the immediate implementation of a comprehensive law against gender-based violence, focused on prevention and social reparation; a law that is capable of incorporating more effective justice alternatives.

“In Cuba, for years, many feminist activists and survivors have accompanied victims of sexual violence – from public stories to others that have not reached the media or the judicial system. We have done it individually, in small groups, with more or less support networks,” explains #MeToo Cuba.

The collective action campaigns that have taken place so far have been key to securing changes in women’s rights. And they continue to take place despite political violence against activists by the government. – Rappler.com

This story was originally published in the Cuban media El Toque and is republished within the Human Journalism Network program, supported by the ICFJ, International Center for Journalists.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Unpaid care work by women is a public concern](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/20240725-unpaid-care-work-public-concern.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[DECODED] The Philippines and Brazil have a lot in common. Online toxicity is one.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/misogyny-tech-carousel-revised-decoded-july-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Why women seek divorce](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-women-seeking-divorce-june-14-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.