SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Twelve Filipinos were able to flee Myanmar’s Shwe Kokko Special Economic Zone or Yatai New City after being allegedly forced to engage in a cryptocurrency scam by Chinese mafia.

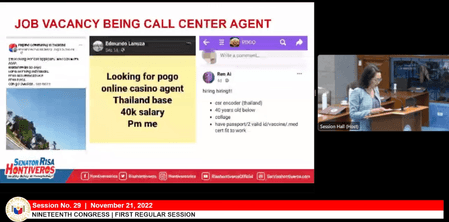

The incident revealed by Senator Risa Hontiveros on Monday, November 22, is one of many human trafficking incidents reported in the economic hub.

The abuses in Myanmar give Philippine authorities a glimpse of the complex web of shadow cross-border operations and how criminals use cryptocurrencies to launder billions of pesos.

What is Shwe Kokko?

Shwe Kokko is a $15-billion development located in the town of Myawaddy, which sits on the Myanmar border with Thailand.

Prior to the construction of casinos, hotels, and other luxury buildings in 2017, the area was a sleepy, underdeveloped village.

According to Frontier Myanmar, Shwe Kokko was built on an area controlled by the Kayin State Border Guard Force (BGF), formerly an insurgency group.

The Kayin BGF partnered with Yatai International Holdings Group – a company registered in Hong Kong and Thailand – to form Myanmar Yatai International Holdings for the venture.

The Myanmar government initially told the group that it could not push through with the project since investments over $5 million would have to secure permits from the Myanmar Investment Commission.

Construction later proceeded, even without permits. The Kayin BGF and Yatai eventually struck a deal with a Chinese business group for the project, and secured a 70-year lease from the Myanmar government.

The Yatai group described the city as a place “where you don’t want to leave” once you visit.

Meanwhile, researchers of the Yusof Ishak Institute said that Yatai also portrayed the area to be a “smart city.” Yatai brought in Singapore-based BCB Blockchain, which would build digital infrastructure for digital payments.

The envisioned smart city, however, was also likely used for online gambling, as blockchain technology allows moving large sums of money without going through Myanmar’s traditional financial system.

Philippine ties

In her privilege speech, Hontiveros claimed that the Yatai International Holdings Group is linked to executives of the controversial Pharmally Pharmaceutical Corporation, a company in Manila allegedly involved in anomalous government contracts at the height of the pandemic.

Hontiveros claimed that Yatai is linked to Linconn Ong of Pharmally.

In an email on Tuesday, November 22, Ferdinand Topacio, Ong’s lawyer, denied the senator’s claim.

“We can understand why Ms. Hontiveros may have been confused. ‘Yatai’ is a generic Chinese phrase meaning ‘Asia Pacific’ and is used as a brand name by many other businesses not even remotely related to each other, such as Yatai Spa and Yatai Ramen. The use of the said generic term does not necessarily signify any business connection, in the same way that Megaworld, Mega sardines and Megamall are totally unrelated to one another,” Topacio said.

Topacio said that Ong was once employed in Yatai International Corporation, a company that manufactures lamps and electric fans.

Yatai International Holdings and Yatai International Corporation are “totally different” entities, according to Topacio.

While Topacio denied that the two companies are related, the chairman of Yatai International Holdings – the company that built Shwe Kokko – still has ties to the Philippines.

In an interview with Frontier Myanmar in 2020, Myanmar Yatai vice president Harry Wang implied that their chairman She Zhijiang, also known as She Lunkai, has several business interests in the Philippines.

“Our CEO runs a number of businesses as part of a conglomerate, including those in the Philippines, which he had started a decade ago. The businesses in the Philippines include a tour agency, a spa, and an online electronic services company – all legal ventures in that country,” Wang said in 2020.

She Lunkai has been accused of having links to crime and has been on the run from Chinese authorities before being arrested in Thailand in August 2022. His extradition to China is still ongoing.

In 2014, She Lunkai was convicted in a Chinese court for an illegal lottery business operating from the Philippines that targeted Chinese users.

Gambling front

Various human rights groups have flagged Shwe Kokko as a means for Chinese gambling tycoons to circumvent Chinese laws.

The Karen Peace Support Network, a group consisting of 30 organizations in Myanmar and Thailand, said that the area was “simply a front” for online gambling by the Chinese mafia.

The group noted that Shwe Kokko was the new hub of online gambling following Cambodia’s ban in 2020.

Meanwhile, the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) warned that criminal actors have used China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to forward illegal transactions, including online gambling.

China has since denied that the Shwe Kokko development is a BRI project, even though news reports said that Myanmar officials have attended at least one BRI-related conference.

Researchers of the Yusof Ishak Institute noted that the gambling industry was able to sidestep laws by building infrastructure in an area run by a BGF, which is not directly controlled by the Myanmar government.

The researchers concluded that what’s happening in Shwe Kokko is not a story of Chinese BRI expansion fueling conflict. Rather, it is a story of “rapacious capitalism seeking new spaces to expand into and exploit, and new jurisdictions to operate from.”

Myanmar once suspended construction in Shwe Kokko due to irregularities, but the February 2021 coup may have been an opportunity for the Chinese mafia to resume construction and operations.

Human rights abuses

The USIP has documented thousands of human trafficking incidents, mostly involving Chinese workers, in Myanmar. Similar incidents have taken place in Cambodia.

When the pandemic struck and China enforced strict border controls, the Chinese mafia had to find new sources of revenue and labor. The mafia sought labor from Southeast Asia and even as far as Africa.

The East African reported that Kenya was “overwhelmed” by distress calls of citizens duped into engaging in scams. Kenyans were tricked into getting jobs in Thailand, only to be forced into crossing the Myanmar border.

Meanwhile, Al Jazeera reported that 130 Indians were forced into cyber scams in Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia. The workers had been held captive and forced to commit digital scamming and forged cryptocurrencies.

Among the 12 Filipinos who were recently rescued from Shwe Kokko is “Rita,” who was presented by Hontiveros at the Senate hearing as a witness. Rita said that the Chinese mafia threatened to beat them with electric batons if they attempted to flee.

Rita said they were forced to use Facebook, LinkedIn, and Tinder to lure people into dubious crypto investments. They even went as far as knowing the victims’ personal lives in an attempt to seduce them into clicking suspicious links.

More questions

In summary, the various news reports and analyses of think tanks point to the following:

- A Chinese mafia evading Beijing’s regulations is running online gambling operations and cryptocurrency scams in Southeast Asia, particularly Myanmar, Cambodia, and the Philippines.

- The mafia initially used Chinese workers, leading to a surge in the Chinese population in areas where online gambling operates.

- When the pandemic struck, the mafia trafficked people from Southeast Asia and Africa to replace the Chinese workers.

- People forced into cyber fraud utilized cryptocurrencies and blockchain to sidestep traditional financial institutions and avoid being tracked.

As authorities crack down on illegal online gambling operations, a new trend has been observed: The rise of text scams.

In the Philippines, telco companies have been attempting to block millions of text messages containing links to online casinos and lotteries.

A similar phenomenon is happening in Cambodia, where online gambling is banned.

The Marcos administration is mulling a ban on Philippine offshore gaming operators (POGOs). Are these text scams their new iteration amid the possible ban?

Hontiveros also urged authorities to probe into the ranks of the Bureau of Immigration. Recall that human trafficking from China to the Philippines involved the so-called “pastillas scam,” where immigration officials got bribes to allow Chinese tourists to overstay and work in POGOs.

“Ang mga sindikatong ito, ‘yung Chinese syndicate at kung meron man silang mga kasabwat sa loob, o sa kung anumang ahensya natin, [parang] learning organism nag-a-adjust, nag-a-adapt, so kaya ganoon ka importante at urgent…na umaksiyon at patuloy na umaksiyon ‘yung mga government agencies natin,” Hontiveros said.

(These Chinese syndicates and their accomplices in government agencies, if any, are like learning organisms that adjust, that adapt, so it is very important and urgent…for government agencies to act immediately.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Finterest] Financial and travel scams to watch out for this Holy Week 2024](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/priest-scammed-january-27-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=395px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[In This Economy] Marcos’ POGO ban is popular, but will it work?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-marcos-pogo-ban.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] POGOs no-go as Typhoon Carina exits](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-graphics-carina-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=424px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.