SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It’s been two months since MT Princess Empress capsized and then submerged off the waters of Oriental Mindoro.

En route from Bataan to Iloilo, the tanker was carrying 800,000 liters of industrial fuel oil when it sank, causing an oil spill that has already affected over 21 cities and municipalities in Batangas, Occidental Mindoro, Oriental Mindoro, Palawan, and Antique.

The disaster, which continues to pose serious environmental threats to marine resources and ecosystems, has been classified as a Tier 3 oil spill since March.

Much has already happened since February 28: the Department of Justice launched its investigation into the incident, the Maritime Industry Authority filed administrative cases against ship owner RDC Reield Marine Services, and President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. this month finally visited the hardest-hit town of Pola in Oriental Mindoro.

Yet until now, data on the oil spill’s effect on marine life and ecosystems remain inconclusive, cleanup has yet to be completed, and coastal communities continue to bear the brunt of fishing and harvesting bans. The leak, meanwhile, is not yet fully controlled, even as fisheries damage had reportedly reached P3.8 billion ($68.40 million) already.

Many environmentalists are already getting frustrated, with some of them using the recent Earth Day celebration to call out the government for its “inadequacy on one of the worst ecological disasters our country has faced.”

In an April 26 statement, advocacy group Philippine Movement for Climate Justice demanded accountability: “How long will it take for them to truly hold the owners of MT Princess [Empress] accountable? It’s been two long months, and their so-called whole-of-government approach has failed to deliver the humanitarian and environmental justice that our communities and ecosystems deserve.”

With the way things are going, Irene Rodriguez, a marine biogeochemist from the University of the Philippines’ (UP) Marine Science Institute, made a rough estimate of when things would go back to normal for coastal communities and the waters of Oriental Mindoro.

“I’m looking at around one to three years for it to be returned back to its original condition, if not better,” she told Rappler in an interview.

Already, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) has estimated a potential environmental damage of P7 billion ($126 million), taking into account “the total area extent of the three ecosystems (mangrove areas, seagrass beds, and coral reefs) that fall within the oil spill trajectories across the three provinces.”

DENR Secretary Maria Antonia “Toni” Yulo-Loyzaga said this estimation would still need verification from the ground.

“How much of these reefs have actually been touched by the oil? How many of the mangroves have actually been destroyed? How much of the seagrass have actually been affected?” she asked in her first live interview since assuming office in July 2022.

Microbes and a whole lot of sunshine

While the country scurries to respond to the disaster with inadequate resources, another parallel story unfolds in the waters where the leak is happening. (READ: Why it’s important to contain the Oriental Mindoro oil spill ASAP)

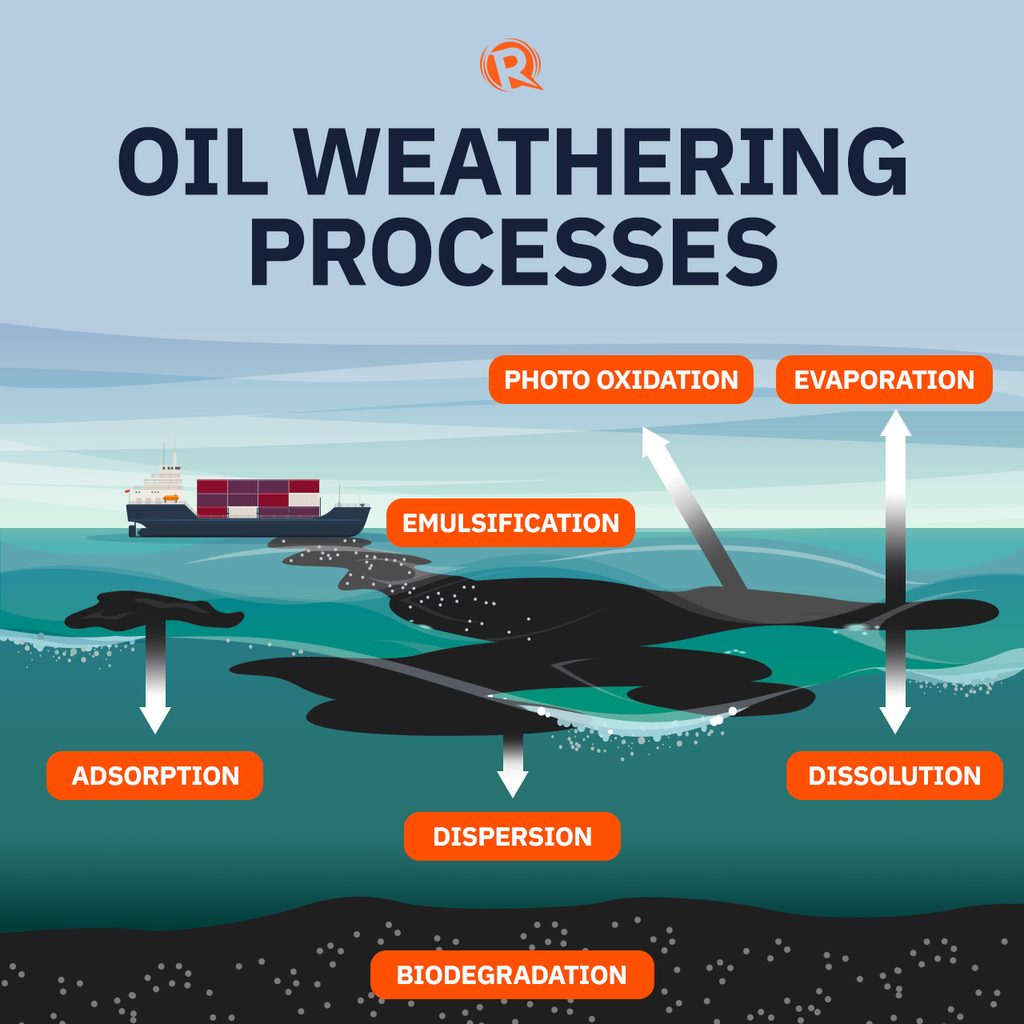

Once oil leaks into the ocean, it undergoes weathering processes that naturally occur whenever oil comes into contact with water. These processes are adsorption, biodegradation, dispersion, dissolution, emulsification, evaporation, and photo oxidation, according to the United States’ weather agency National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Depending on sea and weather conditions, these processes can happen simultaneously.

Rodriguez, an associate professor at UP MSI, explained some of these processes in an interview with Rappler. UP MSI has been tapped by the DENR to provide data and projections on the oil spill.

When oil disperses, Rodriguez said “the natural organisms that are present in the environment will be able to break it down or convert it.”

“When oil disperses in the waters, microbes will naturally come and degrade it. When oil is reduced, it becomes more manageable for microbes to break it down,” Rodriguez said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Some microbes in the ocean use oil as their source of energy. They can easily degrade hydrocarbons, the compounds that make up oil. This process is called biodegradation. These oil-eating microbes readily respond in the event of an oil spill.

Sunlight, on the other hand, photooxidizes oil, which results in the degradation of oil. Sunny days also mean higher chances of oil evaporation.

The first 48 hours after the spill is the most crucial, as oil’s contact with water would kickstart the weathering processes. Rodriguez said that within 48 hours, experts estimate that half of the oil would remain on the surface, around 40% would be dispersed because of natural processes, and about 8% would evaporate.

In the case of the Oriental Mindoro oil spill, it was within the first 48 hours when the Philippine Coast Guard declared the tanker to be fully submerged, and it was a little over that time frame when the town of Pola declared a state of calamity.

According to Loyzaga, her department had been speaking with Oriental Mindoro Governor Bonz Dolor since the first day. “On day two, our teams are already testing the water and testing the air,” she said.

But a full week passed before the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority determined the general location of the tanker.

Prevailing sea conditions affected the oil weathering process in the first two days of the oil spill. Rough seas that caused MT Princess Empress to capsize made leaked oil disperse faster. In the following days and weeks, oil evaporated because of heat and sunlight.

But these conditions present a “double-edged sword.”

While they hasten the dispersion of oil spill, rough seas actually hinder vessels that put out booms and skimmers.

“‘Yung booms mo will not work kapag malakas ang alon at malakas ang agos ng tubig,” said Rodriguez. “‘Pag nangyari ‘yun, mag-i-improve naman ang dispersal ng oil.“

(While booms will not work if the waves and currents are strong, on the other hand, oil dispersal improves.)

Race against time

While microbes are ubiquitous and the Philippine climate allows for a whole lot of sunlight, cleaning up the oil spill is a time-sensitive matter. Humans must intervene to prevent ecological and economic damage.

In the Oriental Mindoro oil spill, urgency is critical since the leak happened in the waters of Tablas Strait, in close proximity to the Verde Island Passage.

Hernando Bacosa, environmental scientist and professor at the Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology, told Rappler that the severity of damage will depend “on the extent of the spread of the oil and the interaction of oil with marine ecosystems and organisms.”

Bacosa has 16 years of experience and research on oil spills. He is currently working on fingerprinting or identification of the oil in this recent disaster.

In the case of the Oriental Mindoro oil spill, Bacosa expressed cautious optimism.

He said coral reefs are currently safe as they are at the bottom of the ocean. The food web in the ocean, on the other hand, may be affected as phytoplanktons and zooplanktons can ingest oil. As they are eaten by bigger fishes, oil creeps up the food web.

While marine organisms can survive, exposure to higher concentrations of oil and their ability to function properly may be reduced. Their lung and heart function, and ability to swim, may be affected. Their reproduction and growth may also be stunted.

However, organisms like fishes and shrimps have the ability to get rid of ingested oil. Mollusks and shellfish can do this too, but they degrade oil a little more slowly than others.

Citing data from the Deepwater Horizon – considered the biggest oil spill disaster in recent history – Bacosa said he is confident that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) would not be found in fish tissues in areas affected by the Oriental Mindoro oil spill.

PAHs are known to be toxic and carcinogenic components of oil. In a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal, PAHs detected in seafood samples in the Gulf of Mexico were found to be in low concentrations, “at least two orders of magnitude lower than the level of concern for human health risk.”

However, it is still necessary to test seafood samples for contamination. The Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) is already conducting toxicity tests on fish but has yet to release conclusive results.

We can be more systematic in responding to these kinds of situations. It can’t wait. It needs an immediate response.

Hernando Bacosa

In a way, a slow cleanup can prove more harmful to the environment.

Bacosa said the speed of an oil spill response largely relies on technology. He compared the Philippines’ situation to countries like the United States, which can seal any leakage even if it’s 1,000 meters deep in the ocean.

“This is slow…. Kasi limited tayo ng technological capability. We don’t have the ability to really siphon, to seal, or to close [the leak]. Wala tayo noon,” he said.

(This is slow…. We are limited by technological capability. We don’t have the ability to really siphon, to seal, or to close. We don’t have that.)

He explained that if oil reaches into the seabed, oil-eating bacteria would not be able to access it, thus, degradation would not be feasible.

“Ito kasing [bunker] oil, ‘pag hindi mo siya ma-clean up, it stays forever kasi heavy molecular weight,” he said. “Once it’s buried in the sand, it could stay for decades, 10 years up to 50 years, kasi hindi siya ma-de-degrade. Kaya you need to manually remove it.“

(This bunker oil, if you don’t clean it up, it stays forever because of heavy molecular weight. Once it’s buried in the sand, it could stay for decades, 10 years up to 50 years, because it will not degrade. So you have to manually remove it.)

The cost of delay

In a bulletin released on April 26, the BFAR said only low-level amounts of PAHs were found in seafood samples in Oriental Mindoro.

“There is currently no sufficient data showing an increasing trend” of PHAs detected, the BFAR reported.

There have been increases in oil and grease detected in water samples in Oriental Mindoro, but these still fall within the acceptable parameters of the DENR.

In Caluya, Antique, there were no signs of oil tainting in examined fish samples. Shellfish from the municipality, however, showed some indications of tainting.

To exercise extreme caution, BFAR recommended that the fishing ban in several areas in Oriental Mindoro be retained until contamination is ruled out.

Inconclusive data causes delay, and it’s the affected communities that bear the brunt of this problem. The latest National Disaster Risk Reduction Management Council (NDRRMC) bulletin on the oil spill said a total of 24,698 fisherfolk, mostly in Oriental Mindoro, have been affected by the fishing ban.

“We could’ve provided better science to support [them], to lift the fishing ban, to provide livelihood for the people,” said Bacosa.

When Bacosa went to Pola, he said people there were lamenting their loss of livelihood, as well as their daily consumption of noodles and canned goods.

More than 40,000 families have been affected by the oil spill, according to the NDRRMC. While they can’t fish, residents are turning to the government’s cash-for-work program for temporary income.

In the initial findings of environmental coalition Kalikasan‘s rapid impact assessment, residents from Pola and Calapan, also in Oriental Mindoro, said government aid was not enough, with 93% of Calapan respondents and 95% of Pola respondents lamenting meager income and saying they need financial support.

These challenges have detrimental effects on people’s mental health and well-being, too. About 24.5% of respondents from Pola reported symptoms of depression due to the oil spill.

“We can be more systematic in responding to these kinds of situations,” Bacosa said. “It can’t wait. It needs an immediate response.”

Wanted: Rehab plans, proper infra

The DENR recently said plans for the rehabilitation of the affected areas were not yet final as the leaking was still ongoing.

But Bacosa said that in other countries like the US, “they have tentative plans and established procedure [already] for rehab even if leaking is [still] happening.”

Gloria Ramos of Oceana Philippines told Rappler, “As this recent disaster clearly unmasks, we simply do not have the resources to contain and minimize hazardous impacts of [an] oil spill apart from the lack of coordination that is so appalling.”

For an archipelagic country, the Philippines also doesn’t have the updated technology yet to mitigate an oil spill. For example, it was the Hakuyo or the remotely-operated vehicle from Japan that determined the exact location of the sunken tanker.

Rodriguez, meanwhile, emphasized the need for proper infrastructure to conduct marine research in the country. With proper knowledge, the country might respond better to disasters like this in the future.

“We’re an archipelagic country, so why can’t we strengthen our capabilities, our capacities to be oceangoing? Not just for fishing activities, not just for tourism or leisure activities, but for research as well,” Rodriguez told Rappler.

She added: “Kung ano man ‘yung natututunan natin sa bawat paglabas, puwede itong makadagdag sa kaalaman. And that will lead to more information and new knowledge.”(Whatever we learn in every expedition, we can add to the country’s body of knowledge.)

Aside from completing the cleanup, experts are already looking at what a long-term rehabilitation looks like in the aftermath of the Oriental Mindoro oil spill.

For Rodriguez, rehabilitation must consist of the following:

- water quality monitoring to determine that waters in Oriental Mindoro and nearby provinces do not contain oil anymore

- monitoring of polyaromatic hydrocarbons in edible marine organisms

- bringing back the livelihood of affected communities

“For rehabilitation to fully come to fruition, we should also focus on the socioeconomic impacts of the oil spill,” she emphasized. “Because we need an energized and incentivized populace to help in the rehabilitation efforts.”

Beyond all these, prevention remains the best solution, said Loyzaga. That, and how people see disasters.

“The first thing we need to do is change the way people think about disasters,” the environment secretary said. “Because right now, people think about response.”

She added, “We need to prevent the risk and that needs to be translated in the policies, in the processes, and in the technical capacities of the people [who] are actually implementing these laws.” – Rappler.com

$1 = P55.56

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.