SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In late October 2022, Alminda Barbin rang the batingting (bell) to alert her neighbors about the imminent Severe Tropical Storm Paeng (Nalgae). After this, she and her family secured their things in a higher spot inside their house. Then, Barbin went to the barangay hall to help with the evacuation efforts.

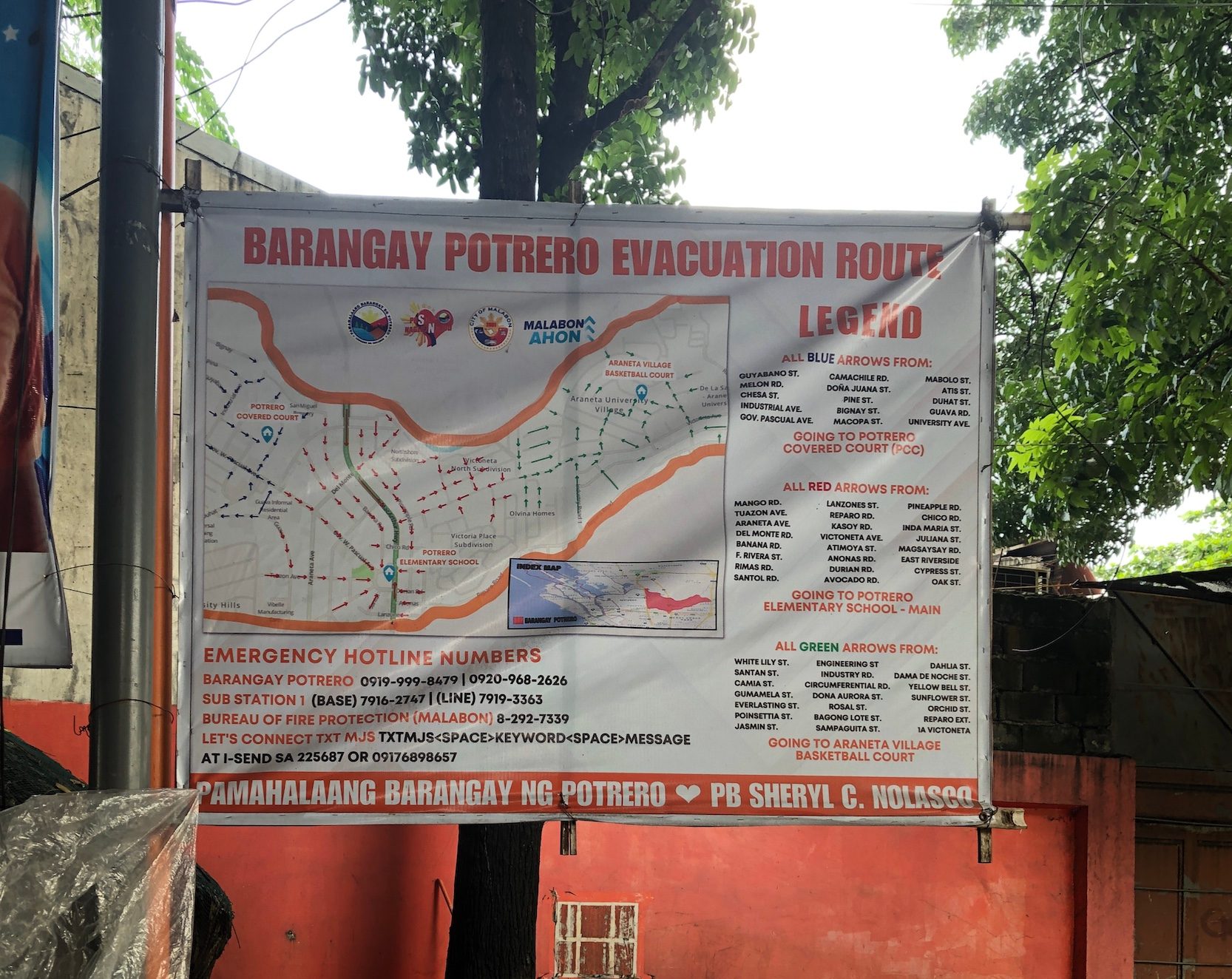

As a community leader in Barangay Potrero, Malabon, Barbin does this routine whenever a storm or any other disaster threatens their area. This is also spelled out in Potrero’s disaster contingency plan, drafted by members of the community.

The plan’s creation was prompted by the community’s experience during Tropical Storm Ondoy (Ketsana) in 2009.

Back then, Barbin thought she was prepared for the storm, but she was shocked when the flood reached the second floor of their house

With no rescuers able to enter their street due to the strong current, Barbin went to her sibling’s house. Along with her neighbors, they waited on the roof, sharing one-fourth cup of rice to get them by during the heavy downpour.

In the face of increasing climate disasters, Barangay Potrero stands out with its community-led contingency plan honed through local collaboration.

Listening to community members

In 2013, Potrero’s barangay leaders gathered their community to participate in a contingency planning after seeing the inadequate response before and during Tropical Storm Ondoy.

Barangay Potrero is the largest in land area among the 21 barangays of Malabon City. It is the city’s second most populated barangay, with over 42,000 residents.

Potrero’s 12 streets are flagged vulnerable areas as the barangay is near the Tullahan River Basin, which flows through the cities of Caloocan, Malabon, Navotas, and Valenzuela up to Manila Bay.

In an interview, former Assistance and Cooperation for Community Resilience and Development, Incorporated (ACCORD) project officer Erica Bucog said that Potrero’s community members were heavily involved in creating the contingency plan. The nongovernmental organization helped facilitate the community’s resilience building.

“From the beginning of the training, community members are part of it, especially those affected by disasters. There are representatives of the homeowners’ association. Local leaders are present, [and] representatives of youth, women, [and] older people,” Bucog said.

“Aside from training them on the technical side of DRR (disaster risk reduction), the community is giving their input here,” she added.

Bucog also said the community created groups in each neighborhood to operationalize the plan by delegating responsibilities to community leaders and members.

Exceptional case

Potrero is an exceptional case in the country’s disaster risk reduction and management (DRRM) landscape.

According to a study by the Philippine Institute of Development Studies in 2021, the DRRM landscape of the country is “still largely top-down,” where authorities call the shots in the process of DRRM.

The study also showed that the government had “minimal investment of participatory-related programs, projects, and activities,” making communities dependent on institutional leadership. Final decisions still rest with local government officials even if civil society organizations intervene.

One factor contributing to the persistence of the top-down approach in the process of DRRM is “path dependence,” according to sociologist and urban studies researcher Dakila Yee.

“It is common, so people already know what they’re going to do; by that logic, the organizational cost is minimal…. If all the work is done by the office, then their planning will be more efficient, and so it will be faster, and they will have organizational benefits,” Yee explained.

In path dependence, the top-down approach in DRRM processes often meets resistance from the community. Decision-makers often find it challenging to explore more effective or efficient alternatives due to deeply entrenched routines. With this, the community members are only left to react and express their grievances after the response and recovery.

Potrero’s inadequate response during Ondoy was attributed to people lacking a clear system of roles and responsibilities.

With the community-led contingency plan, Potrero residents make sure that people know what to do even before a storm hits. This includes the relocation of most residents from the high-risk areas.

Walter Guevarra, a barangay councilor of Potrero, described the system that works best in their barangay: in times of disaster, the barangay council is called, and each committee is given a task. Some of the tasks assigned are based on their committees, which include the search and rescue committee, security committee, and evacuation committee.

Local groups such as the Potrero United Youth Organization and Potrero United Neighborhood Association are also mobilized, Guevarra said.

In 2022, Severe Tropical Storm Paeng tested the viability of Potrero’s contingency plan. Guevarra shared that the community members saw the essence of disaster preparedness.

“During Paeng, we were ready because we knew what we could do. The barangay was knowledgeable, the community was knowledgeable, they knew what to do…. We were ready one day before the storm came,” Guevarra said.

Disaster justice and climate justice

For Barbin, co-creating a contingency plan that includes community members like her serves as a reminder of justice, particularly for someone who experienced Ondoy.

“Because I’m also part of the contingency plan, it’s a massive help because I have knowledge and preparation – that’s justice for me,” Barbin said.

“The community is with us in planning…. They are the ones who say how far the flood will reach. They are reporting and sharing information with us, so it is very important that those in the community have knowledge,” she added.

Disaster justice refers to the equitable distribution of benefits for and responsibilities of disaster survivors. It also tackles how responsibilities are recognized and why there is a disaster in the first place.

Yee sees the co-creation of plans as a good starting point in achieving disaster justice.

“It’s a good step to include people in the development of plans…. For me, it can be even deeper…. For all cases in the Philippines, I want, at the very least, consultation to be the most basic and minimum level,” he said.

Sustaining people’s participation

Amid national recognition for their community-led plan, Barangay Potrero leaders face the challenge of sustaining support from community members in implementing and updating the contingency plan.

Guevarra said they regularly update contingency plans. For instance, they added a response plan for pandemics like COVID-19. Community members also attend quarterly meetings.

ACCORD executive director Sindhy Obias said that crafting the contingency plan had to be facilitated creatively for it to be attractive to Potrero residents.

“People are also busy with various activities, and their survival depends on those. How do we encourage them to participate in training when their daily concerns revolve around finding food, livelihood, and more? Those are the concerns that will coincide while conducting the training,” she said.

Guevarra also shared the frustration of carrying out the contingency plan during typhoons, especially in conducting early evacuation.

“We only face a bit of difficulty there – during evacuation. Even if we had already previously announced that the water level will rise, someone will still call the barangay for help, saying, ‘We are coming out,’ at the point when the water is already high,” he said.

But with the contingency plan in place, Barbin, her family, and her neighbors did not worry much when Paeng hit Malabon.

“The contingency plan we prepared worked. We are now more prepared to promptly address the problems that we used to have difficulty finding a solution [to]. Even before the typhoon arrives, we already have something to face. We can handle it,” Barbin said. – Rappler.com

This story was supported by ClimateTracker Asia and the US Embassy in Manila.

Jhona Reyes Vitor is a freelance writer and journalist focusing primarily on mental health, culture, and climate and environment. She is a former volunteer under Rappler’s Research unit.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Killings continue in Camanava: 20-year-old slain in Malabon](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/09/tcard-2.png?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.