SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

NORTHERN SAMAR, Philippines – In the vastness of the Philippines’ archipelago, 15 kilometers from each and every coast doesn’t seem like much. But to municipal fishermen, it’s their shot at a fair chance in a heavily commercialized fisheries sector.

The Fisheries Code marks 15 kilometers from the coastline of cities and municipalities exclusive to local fisherfolk. Any fishing vessel weighing three tons and above is not permitted to fish there, with some exceptions which could be granted by the local government unit (LGU).

In most cases, this essentially means that the 15 kilometers is for the smallest fisherfolk alone.

However, with talks to amend the Fisheries Code, and given support from no less than President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., fishermen fear losing their exclusive access to their fishing grounds to commercial boats.

Environmental groups have sounded the alarm on Marcos’ push for an amended Fisheries Code to “protect both” fisherfolk and fisheries, and aquatic resources.

According to them, this likely resulted from the continuous lobbying of big fishing firms to operate within municipal waters.

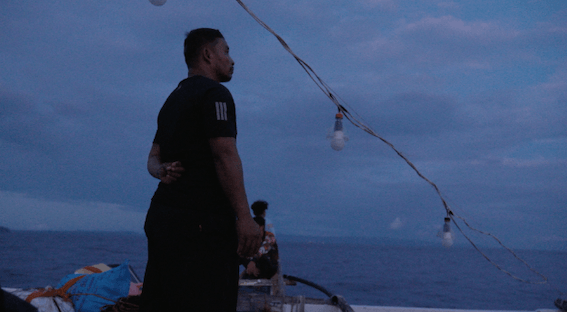

“Kami ‘yung unang-unang masasagasaan dahil sa amin nga lang, halos wala nang mahuli, tapos dadagdagan pa ng malalaking [bangka], mas lalo kaming maaapektuhan,” said Adrian Bonabon, a fisherman in Allen, Northern Samar.

(We would be the first to take the hit because even now, we barely catch anything, and then you add large fishing boats into the equation. We would be greatly affected by that.)

In response to the President’s proposal for amendment, international conservation group Oceana said on July 26 that the Fisheries Code already “provides a science-based, participatory, and transparent mechanism” to sustainably manage the country’s fisheries.

The group added that the government must “prioritize the implementation of transparency measures that are critical in combating illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing” that is already included in the Fisheries Code through Republic Act 10654 – the law amending the code to include regulations against IUU fishing.

Monitoring violations

To combat IUU fishing and protect the interests of small fishers, the Philippine government sought to implement vessel monitoring measures (VMMs).

This is a system that tracks and monitors the position, course, speed of commercial fishing vessels.

Despite the well-intentioned efforts of the Department of Agriculture and the Bureau of Fisheries Aquatic Resources (DA-BFAR) to implement such a system, this has faced opposition from commercial interests.

According to the 2022 Philippine IUU Fishing Assessment Report, 102 million kilograms of fish were caught by vessels without permits.

In 2020, DA-BFAR released Fisheries Administrative Order No. 266 (FAO) to implement VMMs and require fishers to install a tracking device.

The order aimed to enhance law enforcement, establish a system that would aid case building and prosecution of fisheries law violations, and ensure the sustainability of the sector.

In March 2023, the Office of the Executive Secretary suspended the implementation of FAO 266. This is in light of the resolution to a case of three commercial fishing operators (Royale Fishing Corporation, Bonanza Fishing and Market Resources Inc, and RBL Fishing Corporation) that sued the government’s electronic reporting system.

The move was met by criticisms from environment organizations.

Oceana said in a position paper last April that the suspension derailed the government’s ability to strengthen monitoring measures and enforce fishery laws.

“The Philippines still falls short in deterring IUU activities mainly because we have not fully implemented a system of transparency and traceability on our fishing vessels. There is only 58% compliance by commercial fishing vessels [with] this requirement,” Oceana wrote.

Then in June 2023, Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin reverted the order and directed the DA-BFAR to continue implementation.

The order, however, excludes “fishing operators which have been granted injunctive relief by the courts, subject to applicable laws, rules, and regulations.”

At risk: protected zones, small fishers

In the multi-island town of San Vicente, the local government is strict about allowing commercial boats inside its municipal waters. With fishing as its main source of income, local officials put their fisherfolk first.

San Vicente Mayor Edgar Catarungan takes inspiration from his elders and how they ran his home barangay Sangputan where, he said, protecting municipal waters allows everyone to eat.

“Kahit hindi ka mayaman dito, basta may pambili ka lang ng bigas, hindi ka magugutom. Bito kasi ang daming isda, dumungaw ka lang sa dalampasigan, marami nang isda ang makukuha mo kahit mano-mano.… Sana pagdating ng panahon, ‘yan sana ‘yung maging resulta ng pagiging istrikto natin doon sa proper town,” he said.

(Even if you aren’t rich here, as long as you can afford to buy rice, you won’t go hungry because there is so much fish. Just look at the beach, you’ll find so many fish, even if you catch them manually. In time, I want that same result of our strict enforcement in the town proper.)

San Vicente is also rich in sardines compared to some towns in mainland Northern Samar.

However, there aren’t many fishermen even if the municipal fishing grounds for sardines are exclusively for them because they don’t have the advanced gear needed.

They have had to yield their resources to municipal fisherfolk of neighboring provinces who are better-equipped.

Meanwhile, 59-year-old Efren Sinadjan, who has been fishing for 33 years in Victoria, feels the effects of climate change made worse by the uncertainty of having fresh catch to bring home to his family.

“Dati kasi sabi ng lolo ko ‘yung hangin ng habagat parang natural lang…. Hindi parang bagyo na ba, name-maintain ‘yung hangin nila noon…. Ngayon talaga, hindi natural yung ihip ng hangin kapag malakas na, kaya natatakot na kami doon sa laot kapag may hangin na,” the father of 12 said.

(Before, my grandfather used to tell me that the winds of the monsoon felt natural…. They didn’t feel like a storm, and they could manage it then. But now, the wind doesn’t seem natural anymore. When the winds get very strong, we get scared when we’re out fishing.)

Sinadjan also attested to occasionally seeing commercial boats in his town’s municipal waters.

For Bonabon of Allen, keeping his gear and fishing boat disaster-resilient remains a challenge. “Sobra-sobrang daming [mga pagsubok]. Nandiyan ‘yung nasiraan ako sa laot, tatlong araw ako palutang-lutang…. Kada palaot mo, hindi mo alam kung makakabalik ka pa nang maayos,” said Bonabon.

(There are many challenges. There was a time when my engine broke down while fishing. I was drifting for three days…. Every time you go out to fish, you are never certain you’ll come back in one piece.)

At the High Court

Despite the latest order to continue implementation, three commercial fishing operators are still excluded from the electronic tracking requirement.

Their case is now pending at the Supreme Court (SC) after the DA-BFAR sought the High Court’s intervention to review whether a regional trial court in Malabon City erred in declaring FAO 266 to have violated the constitutional rights of the operators.

Operators, who have been following the government’s requirement of manual tracking, cited trade secrets that could be revealed through the real-time monitoring of satellite transponders.

Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra said last October during the first round of oral arguments, that a declaration of unconstitutionality of FAO 266 “renders the State powerless in its efforts to honor its international commitments.”

The solicitor general cited the Philippines’ commitment to international treaties on marine conservation such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Guevarra also said that the Philippines is a member of several Regional Fisheries Management Organizations, treaty-based bodies concerned with the sustainability of shared fish stocks through international cooperation.

“It stands to suffer economically for failure to comply with traceability requirements of countries to which our fisheries products are exported,” Guevarra said in his opening statement in October, speaking on behalf of petitioners DA, BFAR, and the National Telecommunications Commission.

Before the oral arguments started, Marcos already directed DA-BFAR last June to craft the necessary documents to implement FAO 266.

The President gave the directive 15 days after the Alliance of Philippine Fishing Federations Inc. told him to brush off “baseless reports” that the European Commission (EC) will issue the Philippines a “red card” for the illegal fishing activities.

Less than a decade ago, the EC slapped a “yellow” card on the Philippines. A yellow card is a warning given to countries challenged in implementing actions against IUU. It is just one step away from trade sanctions and a red card that identifies a country as “non-cooperating.” The yellow card was lifted a year later.

As of writing, the Philippines still has a green card status, issued to countries that are cooperative with the EC’s IUU regulations.

Finding social justice

Even in protected zones, there are times the fishermen of Northern Samar come home with nothing at all. Ronel Bulan, a fisherman from San Vicente, noted how commercial fishing methods can sometimes lead to overfishing.

“‘Yung commercial fishing, halos mauubos ‘yung isda diyan eh. Oh, paano ‘yung taga-isla, ‘yung dito sa bayan namin, o ‘yung mga maliliit na mangingisda?” said Bulan. (In commercial fishing, they barely leave any fish behind. So what happens to us island residents? What happens to those who live here, or the small fishers?)

Ronel Damiar, a fisherman and sea patroller hired by the San Vicente LGU, is in favor of implementing VMMs.

Even now, enforcing current ordinances on illegal fishing can sometimes pose a challenge for sea patrollers like him due to lack of advanced gear. Damiar recalled a time they confronted an illegal fisher who realized they were police services, and was able to get away because they had a speedboat.

Some things on his “wish list”: a speedboat, a nightvision telescope, a radio, and some flashlights.

“Opo, [sang-ayon ako sa pagkakabit ng vessel monitoring system], para madali silang ma-monitor kung pumasok na ba sila sa municipal water…. At saka kung magkaroon ng mga bagyo, madali silang ma-monitor kung saang area sila banda,” said Damiar.

(Yes, I’m in favor of requiring the installation of vessel monitoring systems so that they will be easier to monitor if they enter municipal waters…. And if there are storms, they will be easy to track no matter where they are.)

Some local governments in Northern Samar, together with their municipal fishermen, are hoping that any plan to open their protected waters doesn’t push through.

Glenn Calipus, San Isidro agriculture officer and general manager of SABELANS (San Bernardino LGU Alliance-Northern Samar), said that the LGUs stand for small fisherfolk. SABELANS is composed of the agriculture officers of the Northern Samar coastal towns near the San Bernardino Strait, a major fishing ground for sardines, and acts as a collaboration ground for policy-making.

“Sila na nga ang nasa laylayan ng lipunan, ipagkakait mo pa? So, ano na ang matitira sa kanila?” he said.

(They are already a marginalized group, and you take more from them? What will they be left with?)

For Bonabon, there is enough space in the ocean for the commercial boats.

“Pabayaan na lang nila sa amin itong mga maliliit na bangka. Kasi kung tutuusin eh, malaki naman ang dagat. Maraming space para sa kanila. Huwag na rito,” he said.

(They should let us be, with our small boats. Because if you think about it, the ocean is vast. There is plenty of space for them. They don’t need to go here.) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler’s Best] The elusive big fish – and big fishers](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/The-elusive-big-fish-%E2%80%93-and-big-fishers.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=220px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Dangers of TikTok](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/dangers-tiktok-april-18-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=309px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.