SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

First of 2 parts

This story was produced by The Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism organization in Washington, D.C. Reporting and writing was contributed by Ian Urbina, Daniel Murphy, Joe Galvin, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Austin Brush.

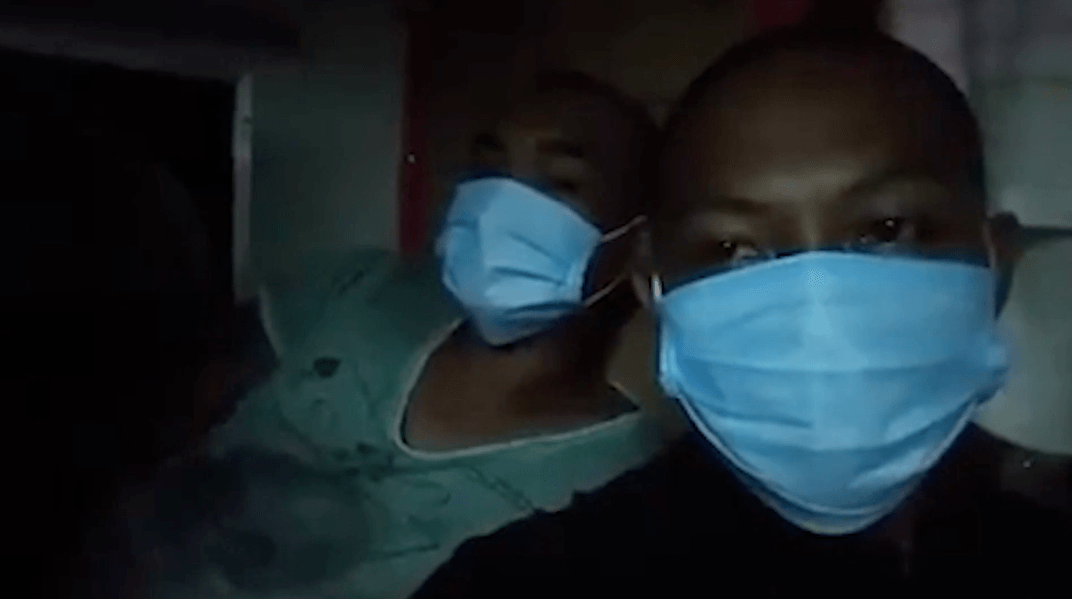

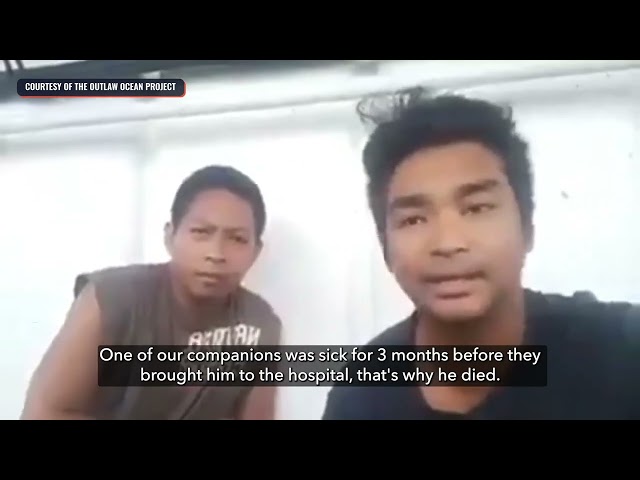

In 2020, several Filipino crew members in a Chinese fishing ship pleaded for their lives in a video. “Please rescue us,” one said. “We are already sick here. The captain won’t send us to the hospital.”

They said that they were sick, but were being prevented from leaving the ship. Three deckhands on the ship died that summer; two of the bodies were put in the freezer, and one was thrown overboard. (The manning agency that placed these workers on the ship, PT Puncak Jaya Samudra, did not respond to requests for comment.)

A four-year investigation from The Outlaw Ocean Project of the Chinese distant-water squid fleet found that, between 2013 and 2021, at least two dozen workers on 14 ships suffered similar symptoms associated with beriberi, a disease caused by a deficiency of vitamin B1. Of those, at least 15 died.

This investigation has also shown that workers are often held captive in inhumane conditions on Chinese fishing ships. Most of the crew aboard comprise migrant workers from Indonesia and the Philippines, making them especially susceptible to forced labor.

In taking the job on a Chinese fishing ship, the Filipino deckhands had stepped into what may be the largest maritime operation the world has ever known. Fueled by the world’s growing and insatiable appetite for seafood, China has dramatically expanded its reach across the high seas with a distant-water fleet of as many as 6,500 ships, which is more than double its closest global competitor. China also now owns or runs terminals in more than 90 ports around the world and has bought political loyalties, particularly in coastal countries in South America and Western Africa. It has become the world’s undisputed seafood superpower.

But China’s preeminence on the water has come at a high human and environmental cost. Fishing is ranked as the deadliest job in the world and, by many measures, Chinese squid ships are among the most brutal. Debt bondage, human trafficking, violence, criminal neglect, preventable injuries, and death are common in this fleet. When the Environmental Justice Foundation interviewed 116 Indonesian crew members who had worked between September 2020 and August 2021 on Chinese distant-water vessels, roughly 97 percent of them reported having experienced some form of debt bondage or confiscation of guaranteed money and documents, and 58 percent reported having seen or experienced physical violence.

The fleet is also ranked as the largest purveyor of illegal fishing in the world. A 2022 review of illegal fishing incidents that occurred between 1980 and 2019, commissioned by the European Parliament, found that nearly half of the cases where the vessel type was identified were committed by Chinese squid ships.

Compared to other countries, China has been not only less responsive to international regulations and media pressure when it comes to labor rights or ocean preservation, but also less transparent about its fishing boats and processing factories, said Sally Yozell, the director of the Environmental Security Program at the Stimson Center, a research organization in Washington, D.C.

Since the overwhelming majority of seafood consumed in the US and EU is caught by Chinese ships or processed in China, she said, it is especially difficult for companies to know whether the products they sell are tainted by illegal fishing or human rights abuses.

When this seafood reaches land, it often goes through processing plants in China using Uyghur labor. In the past decade, the Chinese government has been forcibly relocating tens of thousands of Uyghur workers, loading them onto trains, planes and buses under tight security, and sending them to seafood processing plants on the other side of the country in Shandong province, a fishing hub along the eastern coast.

In 2022, the UN said that Chinese government documents indicated coercion was used to place Uyghur “surplus laborers” in transfer programs. In the same year, the International Labor Organization expressed “deep concern” over China’s labor policies in Xinjiang, noting that coercion was built-in to the regulatory and policy framework for labor transfers.

By searching company newsletters, annual reports, and state media stories, the investigation found that in the past five years, more than a thousand Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities have been sent to work in at least 10 seafood processing plants.

The Chinese government also bolsters its seafood industry with workers from North Korea, primarily in processing plants in the border province of Liaoning, located in northeast China. The North Korean government has, for the past 30 years, sent citizens to work in factories in Russia and China, and to put 90 percent of their earnings – amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars per year – into accounts controlled by the government.

As of November 2022, more than 80,000 North Koreans were employed in Chinese border cities, including hundreds in seafood plants. Videos from the Chinese social media app Douyin show North Korean female workers in seafood factories as recently as November 2022 in Dandong and Donggang.

Most deckhands around the world get their jobs through so-called manning agencies. Hundreds of these firms operate globally, playing a vital role in supplying crew members from dozens of countries to ships that are almost always on the move. The firms handle everything from paychecks and plane tickets to port fees and passports. For the men they recruit, these firms promise an open doorway to another, more lucrative life.

They end up signing contracts that stipulate there would be no overtime, no sick leave, 18- to 24-hour workdays, seven-day workweeks, and a $50 monthly food deduction. If the fishing vessel was not near a convenient port of repatriation, the contracts permitted captains to extend their stay on board indefinitely. Captains were also granted full discretion over reassigning crew members to alternate ships. Wages were to be paid not monthly to families but in full only after completion of the contract, a practice that is illegal in most countries.

Their contracts could require that they pay a processing fee for recruitment, which was to be deducted from their salary. Since the men did not have the money to pay the upfront fees for access to the job, they were required to give the agency their diplomas and family cards as a form of collateral, which were to be returned to the men’s families once the fees were deducted from the men’s salaries. Having initially been told by recruiters that they would make upwards of $450 per month, the men soon learned that the actual salary would be far less, typically around $300.

Greenpeace Southeast Asia, January 16, 2016

This is also when the men learned about a range of salary deductions. These deductions would have been loosely explained amid a flurry of paperwork, rapid-fire calculations, and unfamiliar terms: “passport forfeiture,” “mandatory fees,” “sideline earnings.” The deckhands’ contracts also included penalty clauses, which said that they would pay up to $1,000 if they left the ship before their contracts expired.

Working 12- to 24-hour shifts, the men typically slept during the day, since squid fishing occurs best at night, with help from extremely bright light bulbs that lure the creatures toward the surface. On the ship, the men slept four to a room in wooden bunk beds, each with one blanket on soggy foam mattresses made wet by walls that sweated with condensation.

Violence is common. Deckhands have described captains hitting them on the head; kicking and slapping them, usually for not understanding instructions given in Chinese; taking too long to untangle fishing lines; or dropping squid on the deck.

The Chinese have established a remarkable presence on the world’s oceans during the past several decades. The effort began in 1985, when the China National Fisheries Corporation (CNFC) dispatched 13 trawlers carrying a crew of 223 men to work the coast of Guinea-Bissau, in West Africa.

Today, CNFC, which is state-run, is the largest distant-water fishing company in the world. CNFC forms the connective tissue for much of the industry, including many of the worst scofflaw ships. It owns over 250 fishing boats and refuel ships, at least six seafood processing plants or cold storage warehouses, and more than 15 refrigeration vessels, or reefers, that carry the catch back to shore.

For most of the 20th century, distant-water fishing was dominated by three countries: the Soviet Union, Japan, and Spain. These fleets shrank in size after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, and as rising labor and environmental standards made it costlier for Japan and European countries to compete in the international seafood market.

But during this period, China invested billions of dollars in its fleet and took advantage of new technologies to muscle in on a very lucrative industry. China has also attempted to fortify its autonomy by building its own processing plants, cold-storage facilities and fishing ports overseas.

Those efforts succeeded beyond any predictions. China has now become the world’s undisputed seafood superpower. In 1988 it caught 198 million pounds of seafood; in 2020, it caught 5 billion. No other country even comes close.

For China, the vast armada has great value that extends beyond just maintaining its status as a seafood superpower. It also helps the country create jobs, make money, and feed its growing middle class. Abroad, the fleet also helps the country forge new trade routes, flex political muscle, press territorial claims, and increase China’s political influence in the developing world.

Political analysts, particularly in the West, say that having just one country controlling a global resource as valuable as seafood creates a precarious power imbalance. Navy analysts and ocean conservationists also fear that China is expanding its maritime reach in ways that are undermining global food security, eroding international law, and heightening military tensions.

“Plenty of countries are engaging in destructive fishing practices but China is distinct because of the size of its fleet and because it uses the fleet for geopolitical ambitions,” said Ian Ralby, CEO of I.R. Consilium, a global consultancy that concentrates on maritime security. “No one else has the same level of state ownership in this industry, no one else has a law that obligates their fishing ships to actively gather and hand over intelligence to the government and no one else is as actively invading other countries’ waters.”

Ralby said that through its distant-water fishing fleet, China is working to establish de facto sovereignty over international waters, by leaning on a terrestrial legal concept called “adverse possession,” which, in essence, grants property rights to anyone who occupies and controls an area long enough. The recent signing by 193 countries of a high-seas biodiversity treaty, which aims at eventually protecting 30 percent of the world’s oceans, is unlikely to change China’s course.

“China likely believes that, in time, the presence of its distant water fishing fleet on the high seas will convert into some degree of sovereign control over those waters and the resources in them,” Ralby said. “With 70 percent of the earth covered in water, any one state’s effort to establish rights and interests over the global commons should be a concern.”

According to Greg Poling, a senior fellow at Center for Strategic and International Studies, there’s another wrinkle in all of this: Not all Chinese fishing vessels actually fish. Instead, hundreds of them serve as a kind of civilian militia that works to press territorial claims against other nations. Many of those claims concern seafloor oil and gas reserves. Taking ownership of the South China Sea, for example, Poling said, is part of the same historical project for the Chinese as taking control of Hong Kong and Taiwan. The goal is to reclaim “lost” territory and restore China’s former glory.

Sometimes, these boats are called into action. In December 2018, the Philippine government announced that it planned to repair an airstrip and build a re-supply pier on Thitu Island, a piece of land contested between the Philippines and China. More than ninety Chinese fishing vessels amassed along its coast, making it unsafe for Filipino ships to approach and delaying renovations.

In 2019, a Chinese fishing vessel rammed and sank a Filipino ship anchored at Reed Bank, a disputed region in the South China Sea that is rich in oil and natural gas reserves. (The Chinese government declined to comment on these matters. But Mao Ning, a spokesperson for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has previously argued that her government had a right to “safeguarded China’s territorial sovereignty and maritime order.”) To be concluded – Rappler.com

NEXT: Part 2 | A superpower of seafood, China, sometimes uses forced labor

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] To the moon and beyond the headlines: Asia’s good to bad, 2023](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/tl-asia-good-bad-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[In This Economy] How can the PH economy become less reliant on China?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/TL-PH-economy-less-reliant-china-December-19-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=280px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] What kind of citizens are we?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/tl-what-kind-of-citizen-are-we.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=333px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Meme of the month si Alice Guo, pero evil of the century ang POGOs](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/animated-alice-guo-crime-pogo-links-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=288px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.