SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Last of 2 parts

Part 1 | To project power globally, China has become the Superpower of seafood

This story was produced by The Outlaw Ocean Project, a nonprofit journalism organization in Washington, D.C. Reporting and writing was contributed by Ian Urbina, Daniel Murphy, Joe Galvin, Maya Martin, Susan Ryan, Austin Brush.

During the past four years, a team of reporters from The Outlaw Ocean Project conducted a broad investigation of working conditions, human-rights abuses, and environmental crimes in the world’s seafood supply chain. Because the Chinese distant-water fishing fleet is so large, so widely dispersed, and so notoriously brutal, the investigation centered on this fleet. The reporters interviewed captains and boarded ships in the South Pacific Ocean, near the Galapagos Islands; in the South Atlantic Ocean, near the Falkland Islands; in the Atlantic Ocean, near Gambia; and in the Sea of Japan, near Korea.

China’s dominance has come at a moment when the world’s hunger for products from the sea has never been greater. Seafood is the world’s last major source of wild protein and an existentially important form of sustenance for much of the planet. During the past 50 years, global seafood consumption has risen more than fivefold, and the industry, led by China, has satisfied that appetite through technological advances in refrigeration, engine efficiency, hull strength, and radar. Satellite navigation has also revolutionized how long fishing vessels can stay at sea, and the distances they travel.

Industrial fishing has now advanced technologically so much that it has become less an art than a science, more a harvest than a hunt. To compete requires knowledge and huge reserves of capital, which Japan and European countries have in recent decades been unable to provide. But China has had both, along with a fierce will to compete and win.

China has grown the size of its fleet predominantly through state subsidies, which by 2018 had reached $7 billion annually, making it the world’s largest provider of fishing subsidies. The vast majority of that investment went toward expenses such as fuel and the cost of new boats. Ocean researchers consider these subsidies harmful, because they expand the size or efficiency of fishing fleets, which further deplete already diminished fish stocks.

The Chinese government’s support of its fleet is vital. Enric Sala, the director of National Geographic’s Pristine Seas project, said that more than half of the fishing that occurs on the high seas globally would be unprofitable without these subsidies, and squid jigging is the least profitable of all types of high-seas fishing.

China also bolsters its fleet with logistical, security, and intelligence support. For example, China sends its squid-fishing vessels a weekly digital index that provides updates on the size and location of the world’s major squid colonies. This helps them decide when and where to chase their catch, and often means that they work in a coordinated manner.

In July of 2022, a reporter from The Outlaw Ocean Project shadowed a group of about 260 Chinese squid ships that were jigging a patch of sea 340 miles west of the Galapagos Islands. At one point during the trip, the reporter watched as the bulk of the fleet suddenly pulled up anchors, in near simultaneity, and moved together to a location roughly 115 miles to the southeast. “This kind of coordination is atypical,” Ted Schmitt, the director of Skylight, an maritime-monitoring program, told me. “Fishing vessels from most other countries wouldn’t work together on this scale.”

The visits to Chinese distant-water fishing ships revealed in stark detail a broad pattern of human rights and labor abuses, including debt bondage, wage withholding, excessive working hours, beatings of deckhands, passport confiscation, prohibiting timely access to medical care, and deaths from violence. Workdays on many Chinese open-water fishing vessels routinely last 15 hours, six days a week. Crew quarters are cramped. Injuries, malnutrition, illness, and beatings are common – as is beriberi, which was one of the first signs of problems that the reporters observed during many encounters.

A trip, facilitated in February 2022 by Sea Shepherd, an ocean-conservation group, included an invitation to board a Chinese squid-fishing ship that was fishing in the Blue Hole, an immensely productive high-seas squid fishery in the South Atlantic, near the Falklands. The captain of the vessel granted reporters permission to roam freely as long as they did not name him or his vessel.

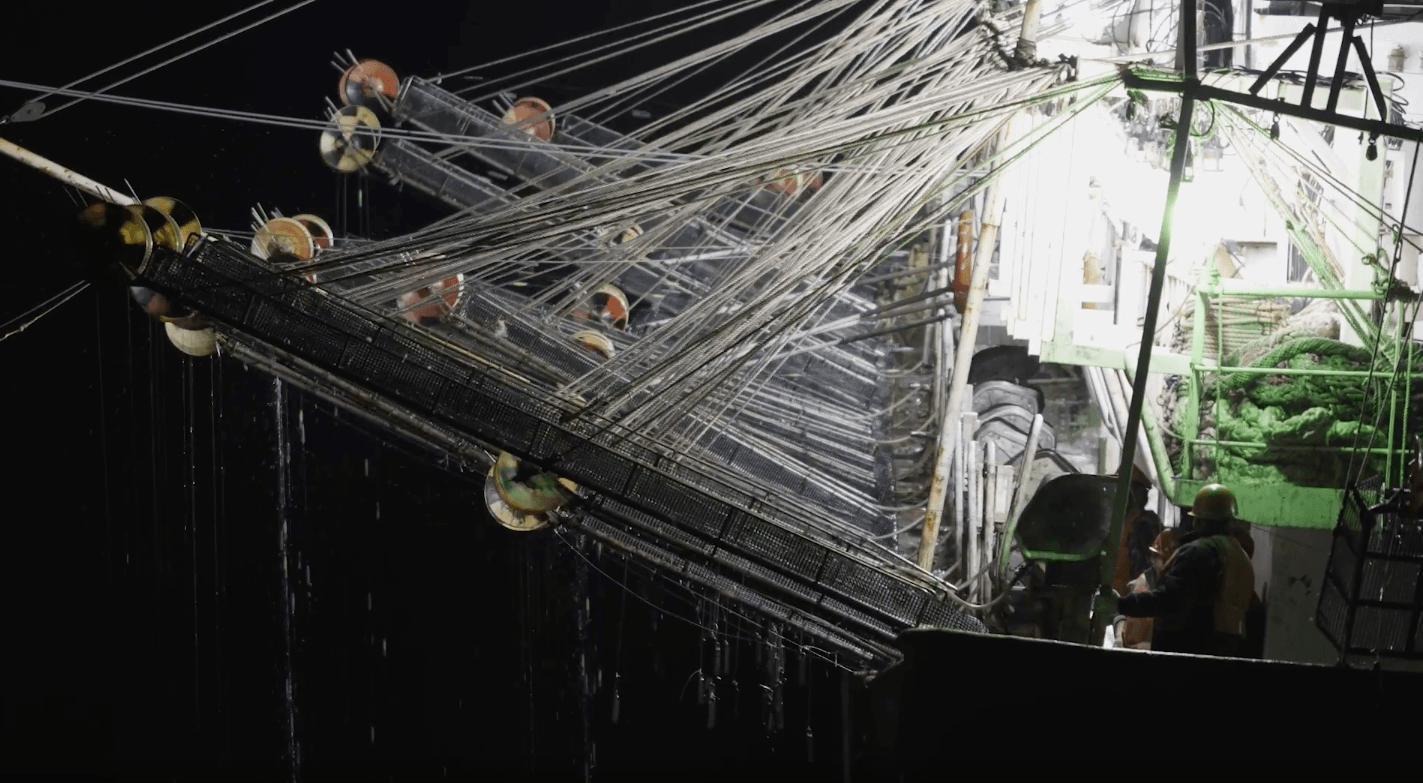

Whenever squid ships are fishing, the heaviest labor happens at night. The ships are festooned with hundreds of bowling-ball-sized light bulbs, which hang on racks on both sides of the vessel and are used to lure squid up from the depths.

As squid are hauled in, the scene on deck often looks like a brightly lit auto-body shop where an oil change has gone terribly wrong. When pulled onboard, squid squirt purplish black ink. Warm and viscous, the ink coagulates within minutes and coats all surfaces with a slippery mucus-like ooze. Because deep-sea squid have high levels of ammonia in their tissue, for buoyancy, the air on board smells powerfully like urine.

The mood on board felt like that of a watery purgatory. The ship had about 50 “jigs” hanging off each side, each operated by an automatic reel. Crew members stationed around the deck were responsible for monitoring two or three reels at a time, to ensure that they didn’t jam. The men’s teeth were yellowed from chain smoking, their skin a sickly sallow, their hands torn and spongy from sharp gear and perpetual wetness. Most wore thousand-mile stares as they babysat their equipment, their expressions recalling a quote from the Scythian philosopher Anacharsis, who famously divided people into three categories: the living, the dead, and those at sea.

Two Chinese deckhands wearing bright orange life vests stood on deck babysitting the automatic reels. One man was 28, the other 18. It was their first time at sea, and they had signed two-year contracts. They earned about $10,000 a year, but, if they missed a day of work for sickness or injury, they were docked three days’ pay. The older deckhand recounted watching a crew member’s arm get broken by a weight from the jig that swung wildly. The captain stayed on the bridge, but another officer shadowed one of the reporters wherever he went. At one point, the officer was called away, and the older deckhand said to the reporter that he was being held there against his will. “It’s impossible to be happy,” he said. “We care about nothing because we don’t want to be here, but we are forced to stay.” He estimated that 80 percent of the other men would also leave if they were allowed. “It’s like being isolated from the world and far from modern life.”

Looking nervous, the younger deckhand ducked into a dark hallway to whisper his plea for help. “Our passports were taken,” he said to the visiting reporter. “They won’t give them back.”

Instead of speaking more, he then began typing on his cell phone, for fear of being overheard. “Can you take us to the embassy in Argentina?”

A minder who kept watch on the men was temporarily called away, which allowed the deckhands to continue their exchange with the visiting reporter. “I can’t disclose too much right now given I still need to work on the vessel if I give too much information it might potentially create issues onboard,” the 18-year-old wrote on his cell phone. “Please contact my family,” he said, before abruptly ending the conversation when the minder returned.

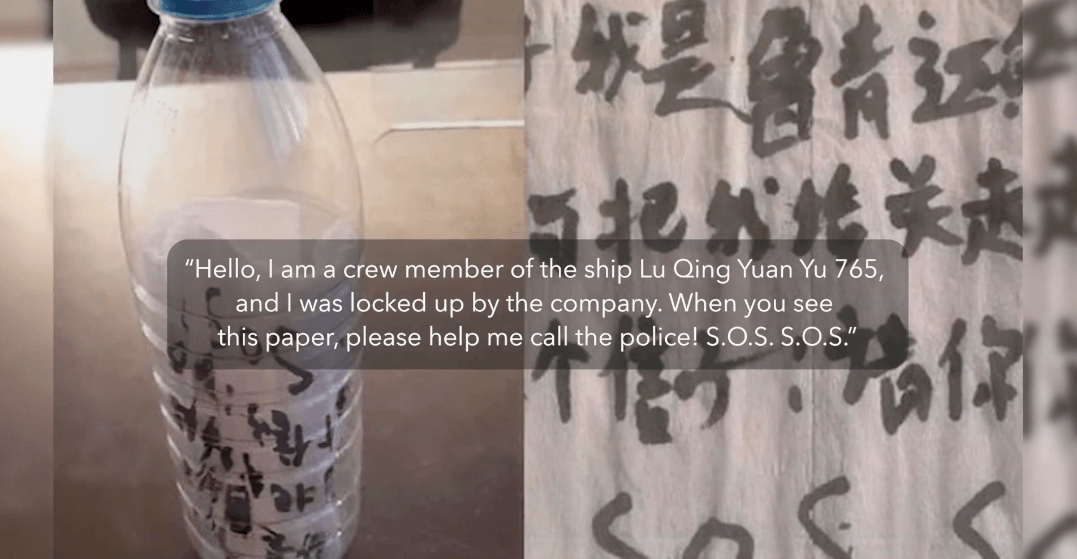

Stories of deckhands held captive on these vessels continue to surface: More recently, in June 2023, a bottle washed on shore a beach near Maldonado, Uruguay, with a message inside from a distressed deckhand on another Chinese squidder: “Hello, I am a crew member of the ship Lu Qing Yuan Yu 765, and I was locked up by the company. When you see this paper, please help me call the police! S.O.S. S.O.S.” (The owner of the ship, Qingdao Songhai Fishery, said that the claims were fabricated by crewmembers.)

In another case, a young Indonesian working roughly 285 miles off the coast of Peru on a Chinese squid ship called the Wei Yu 18 begged the foreman to send him back to shore for medical care. The foreman refused, instead giving him the equivalent of ibuprofen and explaining that his contract had not ended. The man, who died, was part of a breakout of beriberi that sickened five other Indonesians, though the rest of the men received care and survived.

In interviews, three Indonesian deckhands that worked on the Wei Yu 18 said they had not worked on the high seas before nor did they realize the risks in taking work through manning agencies. Under the definition set by the UN International Labor Organization, forced labor exists when two criteria are met: involuntary work and coercion. Multiple examples of these criteria were found on the Wei Yu 18, according to a confidential investigation of the ship produced in July 2020 by C4ADS, a security research firm.

“The Indonesian fishermen reportedly asked to leave after one year on the vessel, but they were not allowed to leave,” said the report, which cited additional factors, including beatings, unsanitary food and living conditions, and debt bondage, and concluded that there was clear evidence of forced labor on the ship.

Victor Weedn, a forensic pathologist formerly with the Washington, DC, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, said that allowing sailors to die from beriberi likely constitutes criminal neglect, since the disease is so easily prevented through proper nutrition or vitamin pills, and since its symptoms can be quickly reversed with proper care. Medical studies show that when B1 is administered intravenously, patients typically recover within 24 hours. Given that, Weedn said, allowing victims to suffer and die over the course of weeks is unconscionable. “Slow-motion murder,” he said, “is still murder.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] To the moon and beyond the headlines: Asia’s good to bad, 2023](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/tl-asia-good-bad-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[In This Economy] How can the PH economy become less reliant on China?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/TL-PH-economy-less-reliant-china-December-19-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=280px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] What kind of citizens are we?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/tl-what-kind-of-citizen-are-we.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=333px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Meme of the month si Alice Guo, pero evil of the century ang POGOs](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/animated-alice-guo-crime-pogo-links-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=288px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.