SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Ilonggo Notes] A love affair with libraries](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/09/Dioso-library.jpg)

Growing up in Iloilo city, I was surrounded by books, thanks to Mom, a pharmacist; and Dad, a doctor, who were both teachers. My aunt became the city’s first librarian. My uncles were voracious readers and subscribers to monthlies like the Reader’s Digest, Pageant, National Geographic and Life, which I devoured with gusto. Mom kept detailed “baby books” for all seven of us, writing on mine: “Recognized the alphabet at two, by four reads nursery books…by five, reads everything – newspapers, the Book of Knowledge, elementary and high school books…comprehension outstanding…”

Prized displays at home were the encyclopedias – Grolier’s (11 volumes) Book of Knowledge (20), and the Book of Popular Science (10). When I was in high school, Mom bought on installment a 24-volume set of Collier’s from a family moving to the US. In addition, we had children’s books – dinosaurs, which fascinated me; the Andersen and Grimm fairy tales; and bunches of comic books. In elementary, we had the Osias series of Philippine Reader books I to VI, handed down from four older cousins, the title page covered with all their names, to which I readily added my own.

My librarian aunt would often give us books for birthdays and Christmas. Once she gave me a book, forgetting that she had given me the same one the year before.

In high school, I finished the school library serials like the Bobbsey Twins, the Hardy Boys, Nancy Drew, and the Agatha Christie mysteries. I spent my 1975 summer break doing YCAP (Youth Civic Action Program) at the city library as an assistant. I dusted shelves, covered books with plastic wrap, and repaired old books by manually boring them with an ice pick, binding and tying them together with “hilo veinte” run through a candle, then threaded into a large sewing needle. Book binding cloth with gum Arabic was applied to the spine. Using this technique, we’d make our own notebooks using leftover ruled paper from examination booklets.

Reading was a great introduction to the big world outside, a source of endless pleasure, firing up my imagination, coloring my dreams and nightmares. Decades later, favorite haunts would be second hand bookstores, and rent-a-book clubs. Wherever work took me, I’d visit public libraries in New York, Washington DC, Baltimore, and London. The Welch medical school library in Johns Hopkins was open 24 hours a day in the 1990s, with couches where students could actually nap. Some of the collections – especially those in the Treasures section of the British Library – made me gasp in wonder. At the reading room of the British museum, I saw familiar names engraved on a plaque of notables who had been there – Rizal, Ho Chi Minh, Dickens, Marx, Darwin, Woolf, among others.

And this is why an initiative of Iloilo City Mayor Jerry Treñas, to have a library in each of the six city districts, is laudable. RA 7743 (1994) mandates public libraries in each congressional district, city, municipality and barangay; 25 years later, a study of the National Library found that merely 3% of the ideal number had been achieved.

Iloilo city, known as an educational center for the region, has eight universities. It had the first government high school outside of Manila, the Iloilo National High School. Molo town, cradle of learned Filipinos, known as “Athens of the Philippines,” had colegios during the later Spanish era and the first public elementary school in the country, Baluarte element would have inspired students to learn more and achieve greater heights as statesmen, feminists, educators, Supreme Court justices, and senators of the Republic.

The city public library is now at the Graciano Lopez Jaena Learning Center in Jaro; it has a sparse collection, and next to nothing on the national hero. Most of the books are donations. This does not befit a city that prides itself on so many other things. It is housed in a new and airy building, has free internet and plug-in connections, and open up to 8 pm six days a week. An average of 30 to 50 people visit daily. Most users are students, board examination reviewees and researchers. Young people say they like the library, since it is “quiet, convenient, conducive and free.” In the past they would go to study hubs, which charge an hourly fee, or study in coffee places and quieter fast food outlets.

One other district, Villa de Arevalo, recently inaugurated its library. Searches for sites for Molo, Mandurriao, Lapuz, and La Paz district libraries are underway. The Iloilo provincial library has started to digitize its collections. Bring your own USB and they will copy stuff for you, though the quality (photo files) remains to be desired. PDFs would be better, or formats which let you turn pages like a “real” book.

Libraries also need to attract more young readers. Storytelling and reading sessions have become regular fare. City librarian Marion Aguirre says they do outreach visits to barangays, and run “read aloud” sessions on their Facebook page. To serve more, reading corners in the local jails, detention and rehabilitation centers have been established. The library has received donations in Braille, and developed work-book type modules for children with learning disabilities. Collaboration with other government offices and private sectors is happening. Special events like National Book week, the Ilonggo book fairs, and occasions like Halloween and Christmas have themed activities. A recent visit to Iloilo by VP and Education Secretary Sara Duterte, with Senior Deputy Speaker Gloria Arroyo in tow, included a visit to the city library where they read stories to children gathered for the event.

The San Agustin University Library and Archives, UPV ‘s Center for West Visayan Studies and the Luce library at Central Philippine University have good collections, but being school libraries, take special effort to access. Other period collections, mainly of the American and early post WW2 era are at the Makiugalinon press and the Rosendo Mejica Museum.

Technology has dramatically changed life and reading habits in ways never before imagined: internet, search engines, social media are everywhere. There is unparalleled access to digitized material that one can easily download or scan. Your whole library can be in a single USB. Online, Project Gutenberg, and specialized photo archives are endless sources of information. Card catalogues, glossy, thick newspapers, and magazines are a thing of the past. One is bombarded with real-time “news” from a variety of internet and cable TV sources. Our keystrokes are monitored incessantly and algorithms determine what we see on our social media feeds. I still prefer holding a book, turning pages, sensing the smell of paper and ink, using a bookmark, and feeling the sort of gloss that you won’t have on a screen. Long trips are an occasion to select a small volume to bring, then conveniently left for others to enjoy.

The annual budget for the city’s libraries is around P2.5 million, increasing each year, but it also includes the salaries for job hires, utilities, subscriptions, so there is not much left for acquisitions. The librarian wishes for Digital “talking books” and subscriptions to sites that offer free downloads, so that “people can just ask us if we have a title, then we can search and send the links to them.”

The most notable of Panay’s public libraries is the Leocadio A. Dioso Memorial Public Library in Pandan, Antique, which I stumbled upon one Sunday a few months back. Named after a former Philippine presidential legal adviser and diplomat, the libraary was assembled from the collections of Dioso’s four children. His son, Leo Jr., established it after retiring from the UN in 2004.

Although privately-owned and operated, the Dioso library functions officially as the municipal library of Pandan. It is the only public library in northern Antique, which has 10 of the province’s 18 municipalities. The 20,000+ volume and DVD collection would put most public libraries in the country to shame. Leo Jr., suave and youthful at 82, showed me the children’s section with its colorful posters, stuffed toys, puzzles and games. We lamented the decline in ranking of Philippine youth in reading and math, now trailing ASEAN neighbors. Since it remains difficult for those from other municipalities and barangays to access, Leo hopes for a mobile library, so that the aims of encouraging reading, literacy, and improving one’s life chances may be achieved.

Palanca Hall of Famer Butch Dalisay sums it up: “Without libraries, I would not be where I am today. I wouldn’t have become a writer if I wasn’t a reader first.” – Rappler.com

Vic Salas is a physician and public health specialist by training, and now retired from international consulting work. He is back in Iloilo City, where he spent his first quarter century.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

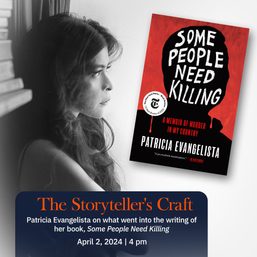

![[Rappler’s Best] Patricia Evangelista](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/unnamed-9-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=486px%2C0px%2C1333px%2C1333px)

![[Ilonggo Notes] Putting the spotlight on Ilonggo and regional cinema](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/Screenshot-2024-04-07-at-2.04.59-PM.png?resize=257%2C257&crop=321px%2C0px%2C809px%2C809px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.