SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The use of Bangui Windmills in Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.’s presidential campaign has become symbolic of the idea that Marcos dictatorship was the country’s “golden age,” according to a new study conducted by University of the Philippines (UP) researchers.

In a #FactsFirstPH briefing on Friday, May 6, professors Daphne-Tatiana T. Canlas and Ma. Ivy A. Claudio of the UP Department of Broadcast Communication, presented their study titled “Building Narratives: stories of greatness and windmills among Marcos Jr. supporters on social media.”

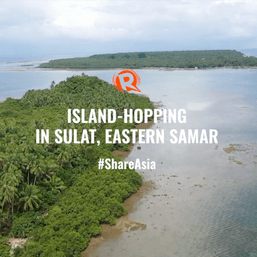

The researchers analyzed the use of windmills which were featured in his very first campaign commercial from December 2021, with his campaign slogan: “Bangon Bayan Muli” (Rise again, my country). Since then, the imagery of windmills have become a fixture in Marcos’ campaign materials.

Canlas and Claudio pointed out the key followings:

- As early as 2015, the Bangui Windmills project in Ilocos Norte has been falsely attributed to Marcos and his time as governor of the province from 1998 to 2007. This has been fact-checked multiple times and proven false, yet his supporters continue to deploy this image.

- The imagery of the windmills repeatedly featured in his campaign commercials, building on the idea that Marcos Jr. offers the country a return to the country’s so-called “golden age” helmed by his parents, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. and Imelda Marcos, during their decades-long dictatorship.

- The insistence on a nostalgic past reinforces what scholars call “grand narratives.” Grand narratives are stories that go unchallenged to claim a universal truth in order to maintain a unified status quo. The Marcos’ dictatorship remains a “grand narrative” and is sustained by Marcos’ current race to the presidency.

- The windmill serves as a metaphor for development that is possible under another Marcos presidency, calling out to the Marcoses’ use of government projects as political propaganda or more commonly called the “edifice complex.”

‘A grand narrative’

The Bangui Bay Wind Farm was established by the NorthWind Power Development Corporation (NPDC), based on a study by the United States’ National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) conducted in 1996. Since 2015, the project has been falsely attributed to Marcos through his supporter pages, and Marcos himself has denied his involvement in the project at all.

Despite this, the Bangui Windmills have been featured in both Marcos’ solo commercials and with running mate Sara Duterte, ultimately becoming synonymous with the “UniTeam” campaign.

Using a textual analysis, the researchers found that despite infrastructure being seemingly harmless, they communicate meaning to the general public.

“Buildings are metaphors for accomplishments, presence, and power [that] have been deployed throughout history. When one thinks about the Eiffel Tower in France, or the Great Wall of China, identities, histories, and stories of the nations and people who built them find a platform here,” the study said.

The study found that just like during the Marcos dictatorship, the rapid building of infrastructural projects was used to project a “grand narrative” that touts this period as the “golden age” of the country.

“The ‘golden age’ narrative is an example of how stories told without context and skepticism can devolve into propaganda. The buildings and the facades they present are taken at face value. It would be easy to believe the ‘greatness’ being projected by these buildings,” the study said.

The term “edifice complex” was first coined by Gerard Lico in his book “Edifice Complex: Power, Myth and Marcos State Architecture,” to describe Imelda Marcos’ infrastructure-building spree as First Lady of the Philippines from 1965 to 1986. Her term produced buildings like the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) Complex, the Manila Film Center, and the Coconut Palace.

However, the researchers also found that the Marcos family’s grand narrative was sustained by selectively promoting these achievements devoid of context, such as the human cost of such projects or the high poverty rates at the time.

“In the Marcosian grand narrative, the glory days of the country are defined by their family’s alleged accomplishments and service, embodied in the edifices the dictatorship – a narrative that plasters over the controversies and true cost of maintaining their image as saviors of Filipino culture and the great initiators of the golden age,” the study stated.

Challenging a grand narrative

Within Marcos’ 2022 race for the presidency, the symbolism of the windmills builds on the Marcos family’s efforts to revive their image by way of historical revisionism and disinformation.

According to the research: “The use of windmills as an icon by Marcos Jr. is a metaphor for development. Synonymous with his presence, Marcos Jr. wishes to replicate that idea of development among various sectors in society. Just as the sight of the windmills are irrefutable proof of their existence, supporters of Marcos Jr. use the same image to refer to his greatness.”

Much of Marcos’ campaign narratives and symbolism promise a return to the supposed Marcosian golden age. From the windmills to his campaign slogan “Babangon Muli” echoing his own father’s December 1965 inaugural speech, where the senior Marcos proclaims, “This nation can be great again.”

Coupled with this powerful metaphor is the well-documented Marcos disinformation system that has been reviving the family’s image across social media. (READ: Tracking the Marcos disinformation and propaganda machinery)

“Why are narratives of grandness and sweeping change easier to accept? It’s easier to hold on to a single narrative and view, instead of many, often contradicting views,” they said.

An example of such grand narratives that have been challenged is the idea of monolithic Filipino identity. By looking towards how as a culture, there is no universal representation of Filipino identity therefore, we should be just as critical of any idea of unquestionable truth or disinformation.

The researchers urged media consumers to be critical to work towards the goal of reestablishing a shared reality, adding: “Help people connect the dots and learn about the context surrounding issues. Tell the small stories. Just as disinformation made use of stories with baseless claims, so should we use contextualized, localized stories based on facts.”

The study is a part of the work being done by #FactsFirstPH to better understand the flow of disinformation in social media during the election period. #FactsFirstPH is a multisectoral coalition of more than 120 groups that seek to combat disinformation ahead of the 2022 national and local elections. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Be The Good] Weave your story into the state of the nation](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-marcos-sona-july-17-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=275px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] Improbable vote](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/03/Newspoint-improbable-vote-March-24-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=339px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] 19 million reasons](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/12/Newspoint-19-million-reasons-December-31-2022.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=181px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

![[In This Economy] Marcos’ POGO ban is popular, but will it work?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-marcos-pogo-ban.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] POGOs no-go as Typhoon Carina exits](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-graphics-carina-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=424px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.