SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This story is part of COVID-19 Pushed Me to Leave the Philippines, a series of profiles of Filipinos who migrated out of the country during the pandemic.

The well-being of healthcare workers has been a constantly thorny discussion since the deadly novel coronavirus came to the Philippines two years ago.

Since then, there have been protests, distress calls, delayed benefits, corruption allegations, and migration. While thousands of Filipinos still contract the coronavirus daily, Filipino health workers are leaving to care for COVID-19 patients in other countries – and some may say we can’t blame them for doing so.

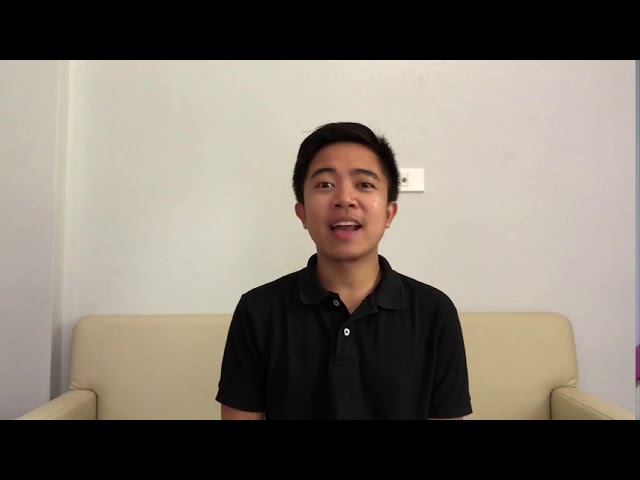

Keannu Arnoco, a Filipino nurse, is one of the health workers who left the country in 2021 to seek an environment that would value the likes of him more. He only regrets not being able to spend more time with his family at home.

In April 2020, the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration barred health workers from being deployed abroad in a bid to preserve manpower in battling a then-unknown virus. The ban was lifted in November that year, but the Duterte government imposed an annual cap of 5,000 instead.

After five years of exposure to the public and private health sectors, Keannu felt sure enough that working in direct COVID-19 care in the Philippine system may not be worth the risk. Now in the United Kingdom, where thousands of other Filipino nurses also practice, he finds security and benefits his home cannot offer.

The Philippines is one of the world’s major sources of nurses. In 2019, almost 17,000 Filipino nurses signed overseas work contracts, according to government data.

Risk and low pay, even before COVID-19

Approaching his seventh year as a registered nurse (RN), Keannu has been exploring numerous areas in the health sector.

A few months after he became an RN in 2015, he volunteered at a public hospital and the city health office in his hometown, Bogo City in Cebu. On his first day, while treating a patient with the contagious tuberculosis disease, Keannu realized how lacking the facility’s resources were.

While the patient coughed up blood, the family continued to gather around the room. Tuberculosis, like COVID-19, can be transmitted through the air.

“They were crying, and the patient was really deteriorating at that time. I was very hesitant because I wasn’t really wearing the appropriate PPE (personal protective equipment). I don’t even remember wearing a mask at that time. That’s why I never came near that patient,” the nurse admitted. Because of his fears, he let the senior nurse he was shadowing take the reins.

“There was not even a single glove there when I asked for it,” he said. “From there, I realized that it’s very hard working in a public health facility.”

While moments like this disheartened Keannu, he went on to have a quick stint working for the Department of Health’s nurse deployment program for a month and a half by the end of 2015, earning P28,000. The DOH was supposed to renew him for another six months, but a private tertiary hospital in Cebu City offered him an opportunity as well.

Here was where Keannu spent a year in the general ward, working with patients with various cases, then working in the intensive care unit (ICU) in his second year. While this allowed him growth and experience, the pay was a measly P13,000 a month.

Keannu, who had siblings and colleagues migrating to other countries, considered going abroad himself after two years at the private hospital. The idea had been in his head for a while, but now he entertained the real possibility of getting out.

Getting ‘hooked’ on advocacy

Just as he was preparing to undergo English proficiency tests that were required in some countries, he pushed back his plans for a few more years because of his passion for another health-related advocacy: addressing the HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) problem in the Philippines.

“I did try to go and review [for the tests], but then I got hooked when I volunteered for an HIV-related advocacy,” he said, adding that he is openly gay and passionate about battling the stigma faced by people living with HIV.

In 2018, he worked in and became president of AIDvocates. He also expanded his work to mental health advocacy, and took a job in the Commission on Population and Development doing coordinating work in sexual and reproductive health programs.

Then, COVID-19 became a pandemic in 2020. But instead of going back to direct patient care, Keannu opted to work with his barangay in Bogo City to develop COVID-19 awareness campaigns. He also became a COVID-19 technical officer for Cebu province in a project by the United States Agency for International Development.

Together with the local government, Keannu conducted trainings for frontliners, developed campaign materials, and did house-to-house visits aimed at spreading information about the new virus, such as signs and symptoms of COVID-19, how it is transmitted, and prevention.

“It was very simple, and it didn’t really need a lot of budget. It was basically just me wanting to help them, and for them to help out others. That was to remove the fear, the stigma, and the discrimination that came with this new disease at that time,” he said.

Keannu believed that this was an alternative way to help Filipinos in his community without necessarily exposing himself to people with COVID-19, considering the risks he already knew from working in patient care.

Ironically, he takes care of COVID-19 patients now in the Isle of Wight in the UK. But, he asks, if he were to provide direct care for coronavirus patients in the Philippines, what would be the cost?

‘This is worth it’

While doing his advocacy work and COVID-19 awareness programs, Keannu had been preparing his migration requirements as well.

In January 2021, he was accepted to work in a trust, or a facility in the UK’s National Health Services. He left for the UK on May 13 – just after the Philippine labor department exempted the UK in the health worker deployment cap. The UK government recognized Keannu as an RN in July after he took an additional exam.

From working in the orthopedic ward for three months, Keannu was transferred to work in the two-unit ICU – the green unit with critically ill patients without COVID-19, and the red unit for COVID-positive patients. He is deployed in either unit, depending on staffing needs.

Keannu laid out his thought process as he ended up doing the work he avoided in his home country: “Do I get the correct or the appropriate return? Do I get what I deserve if I work [in this place]?”

“This is a risk, but I know that, for example, I’m well-protected because the PPE is enough. It’s very different from the Philippines…. I also considered the compensation and the benefits that we have here. So, I thought, okay, this is worth it,” he added.

While health workers in the Philippines dealt with delayed benefits promised by the government, Keannu said supervisors in the UK would encourage nurses like him to take their leaves if they hadn’t yet, “because [they] deserve it.”

Now earning multiple times more than any job he had in the Philippines, and finally feeling like his work and well-being are prioritized, Keannu has no regrets.

“Honestly, I don’t have any guilt [in leaving the country] because – does the government have any guilt about us not being treated fairly? If they’re not guilty about how they treated us, then why should we be guilty of not treating the people there, when we’ve always been there to provide care?”

Keannu laments how numerous Filipino medical worker groups fight for the benefits they deserve, but “it takes time for us to be heard.”

In August 2020, overwhelmed medical frontliners appealed to the government to impose a two-week hard lockdown in Mega Manila as the country dealt with a “losing battle” against COVID-19. President Rodrigo Duterte taunted them in response: “If you mount a revolution, you will give me a free ticket to stage a counter-revolution. How I wish you would do it.”

Keannu reflects, “We’ve always been there for COVID-19. But the question is, has the government been there for us? I don’t think they have. Because, why do we still want to go abroad?”

While secure and well-compensated in the UK, Keannu is not closing his doors to coming back to the Philippines. He thinks, if working conditions were better and he could just travel temporarily to explore the world, why not?

“If I’m stable here, if I like it here, then I might stay here. If I don’t, I might return to the Philippines or, if not, I might be in any other part of the world,” he said. “That’s something valid and acceptable because that’s life. And where there is life, we try to just keep on going.” – Rappler.com

Read other stories from this series:

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] Hippocrates and hypocrites](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-medical-ethics-june-27-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=314px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Beyond infrastructure: Ensuring healthcare access for the poor](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-healthcare-access-03402024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[EDITORIAL] US Supreme Court on Trump’s immunity: Punyal sa puso ng Amerika](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/animated-trump-scotus-presidential-immunity-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=263px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.