SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Picking a new chief justice will be the next test for President Rodrigo Duterte and will also be pivotal for a Supreme Court that is under intensifying pressure from lawyers to act more decisively on human rights.

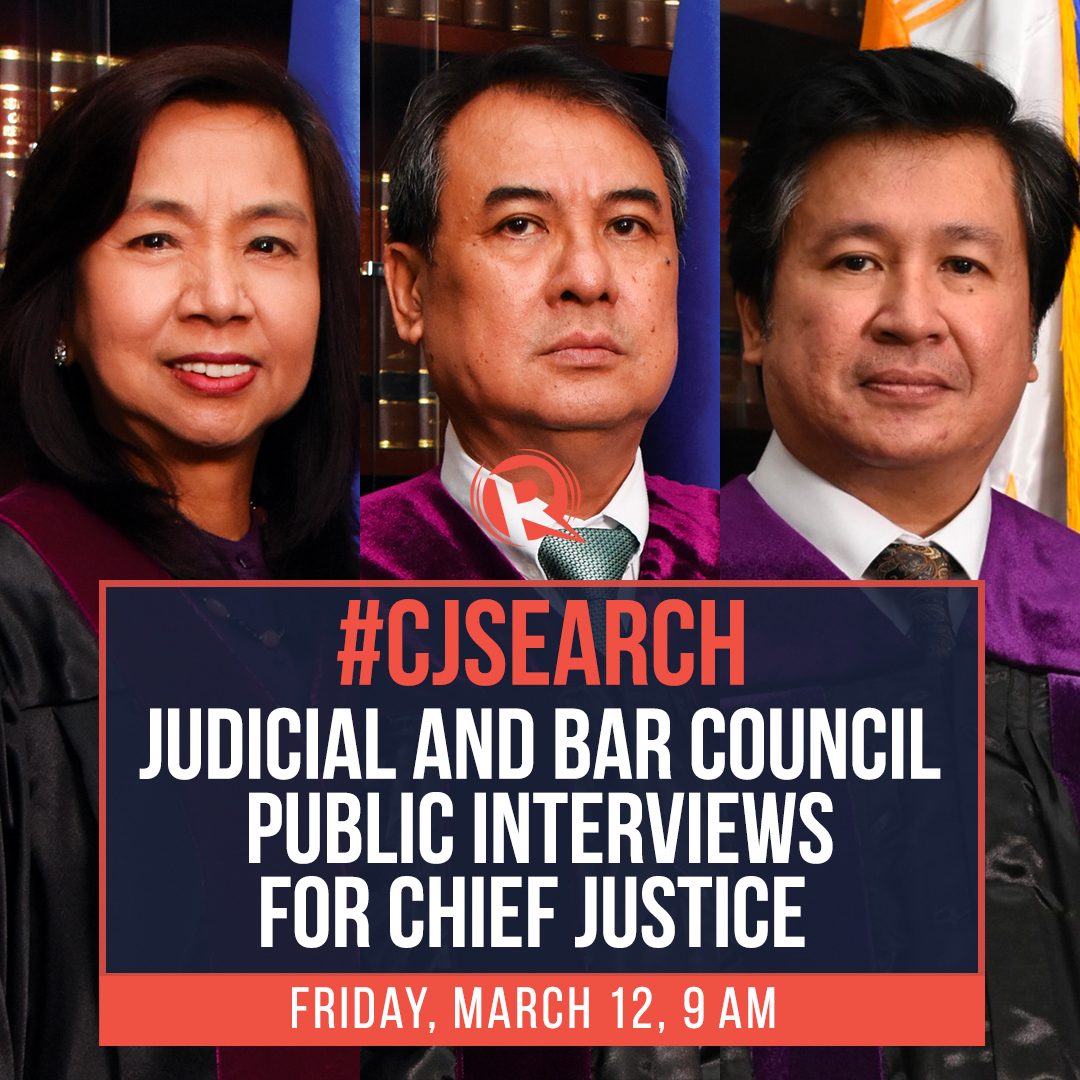

The 3 applicants – Senior Associate Justice Estela Perlas-Bernabe, Associate Justice Alexander Gesmundo, and Associate Justice Ramon Paul Hernando – will be interviewed by the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC) on Friday, March 12, starting at 9 am.

The interviews are not intended to further narrow down choices since the JBC is bound by the constitutional rule that a shortlist should be a minimum of 3. In many ways, the interviews would be for the benefit of Duterte and the public.

A crucial segment of that public would be the lawyers, who have been restless the past few months because of the increasing number of killings and attacks in the legal profession.

The stabbing in the head of Iloilo lawyer Angelo Karlo “AK” Guillen last week pushed lawyers to risk contempt by making public statements to pressure the Supreme Court to stop the anti-terror law and de-escalate the situation.

“Itanong ng JBC sa mga nag-a-apply sa chief justice ano ang posisyon niyo sa sinasabi ng Malacañang na bale-wala ang human rights,” said Neri Colmenares of the progressive National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL) at a press conference on Tuesday, March 9, made despite a gag order from the Court.

(The JBC must ask the chief justice applicants what their position is on Malacañang’s disregard for human rights.)

Colmenares was referring to Duterte’s recent speech telling law enforcement agents to “ignore human rights” and immediately kill communists. Colmenares added the JBC must ask the 3 applicants about the killings of drug suspects and killings of activists.

Power of a chief justice

If the JBC were to consider public sentiment in its questions on Friday, these would be among the top issues on its agenda.

A statement co-signed by no less than former colleagues, retired justices Antonio Carpio and Conchita Carpio Morales, says the Supreme Court “must take immediate measures to stop these attacks including those committed against petitioners and counsel in the Anti-Terror Act petitions.”

But what can a chief justice do, if he or she is only one in a bench of 15? The chief justice is, after all, primus inter pares or first among equals.

The chief justice can instigate the creation of special committees, like what former chief justice Maria Lourdes Sereno did in 2016. She, Carpio, and retired former justice Presbitero Velasco Jr authorized the creation of a technical working group (TWG) that would assess whether existing human rights mechanisms were still effective.

This group was Sereno’s answer when asked during her time how the Court can address killings in Duterte’s drug war.

The Supreme Court is a passive institution by design, but Sereno’s TWG invoked the Court’s constitutional power to promulgate rules. This was the same power invoked by then-chief justice Reynato Puno when he held a rare national summit in 2007 to address human rights abuses under former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo.

The result of that rare display of judicial activism under Puno was the promulgation of the rules on the writs of amparo and habeas data – protective writs availed of by activists who are harassed or surveilled.

Sereno’s TWG also aimed to review if those writs were still effective. But nothing was ever heard of again from that TWG until Sereno was ousted in 2018.

At a press conference in June 2020, outgoing Chief Justice Diosdado Peralta said he would look into it. Peralta currently heads the Court’s committee on rules.

At a budget hearing at the House of Representatives last year, Court Administrator Midas Marquez said that Peralta as head of that committee would review how those writs could be strengthened, in the wake of activists being killed without ever being able to avail of those remedies.

Again, nothing was heard of from this review. The Court’s Public Information Office (PIO) has not answered repeated queries about it.

The seniority line

Gesmundo and Hernando are Duterte’s appointees, and a young appointee who would serve beyond his term would be to his benefit.

Gesmundo retires in 2026 and Hernando in 2036. Hernando has the San Beda connection to the President, too.

Bernabe’s ties to Malacañang is through her son, who works at the Office of the Executive Secretary. Bernabe has said before that she and her son are “governed by the separation of powers doctrine.”

Bernabe’s clear edge, however, is seniority, which is Duterte’s favorite test when it comes to appointing any justice.

Bernabe is the most senior of the 3. She is, in fact, the most senior after Peralta. The next two in the seniority line – her fellow Aquino appointees Marvic Leonen and Benjamin Caguioa – opted out of the applications.

Gesmundo is no. 4 and Hernando is no. 5, appointed only in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

But if Duterte were to go with either Gesmundo and Hernando, Malacañang can try to argue that it is not the years in the Supreme Court that count, but the years in the judiciary in total. This was the case when Duterte picked Lucas Bersamin over the more senior Carpio in 2018.

Bernabe still wins that test, however, with an accumulated 25 years in the judiciary – from being a lower court judge to a justice of the Court of Appeals (CA). Gesmundo has 16 years, 12 years as justice of the Sandiganbayan. Hernando has 18 years, also as a lower court judge and CA justice.

But Malacañang could say Gesmundo has been in government for 36 years, ever since he started out as trial attorney at the Office of the Solicitor General in 1985. Hernando has been in government 23 years, since being a prosecutor beginning 1998.

Whichever way Duterte goes will have a lasting impact, as his pick will steer the Supreme Court as it navigates this time in history when civil liberties of Filipinos are under threat.

A quick review of their judicial principles can be found here.

Watch the JBC interviews on Friday, March 11, starting 9 am. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.