SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In its latest decision, the Supreme Court (SC) said there was a different standard for determining a minor’s liability in crimes.

In a ruling penned by Associate Justice Rodil Zalameda, the SC issued guidelines on how to determine what is termed as “discernment” of perpetrators for crimes involving children in conflict with the law (CICL) or minors who committed criminal offenses.

Discernment here refers to a child’s capacity, at the time of the offense, to understand the difference between right and wrong. This also includes the minor’s capability to know the consequences of the offense.

The High Court’s clarifications stemmed from a case involving an unnamed minor found guilty of homicide. In that case, the SC denied the petition for certiorari that sought a review of a decision made by a lower court.

Besides discernment, the SC listed and explained the other relevant guidelines as follows:

- Roles. First, a social worker should determine the perpetrator’s discernment, to be followed by the court. In determining discernment, authorities should take into account the ability of the child to understand the moral and psychological components of criminal responsibility, and the consequences of the wrongful act. They should also take into account whether a minor can be held responsible for essentially antisocial behavior. The social workers’s assessment is for evidence purposes only, and the court has the final say in determining discernment, “based on its own appreciation of all the facts and circumstances in each case.”

- No presumption. The SC said there should be no presumption that a minor acts with discernment. The prosecution is mandated to prove as a separate circumstance that the alleged crime was committed by a minor with discernment. “For a minor at such an age to be criminally liable, the prosecution is burdened to prove beyond reasonable doubt, by direct or circumstantial evidence, that he or she acted with discernment,” the SC added.

- Criteria. The SC said courts shall consider the totality of facts, including circumstances in each case. This includes:

- (I) The very appearance, the very attitude, the very comportment and behavior of said minor, not only before and during the commission of the act, but also after and even during trial

- (II) The gruesome nature of the crime

- (III) The minor’s cunning and shrewdness

- (IV) The utterances of the minor

- (V) The minor’s overt acts before, during and after the commission of the crime

- (VI) The nature of the weapon used

- (VII) The minor’s attempt to silence a witness

- (VIII) The disposal of evidence or hiding of the corpus delicti (“body or substance of the crime”)

Why this matters

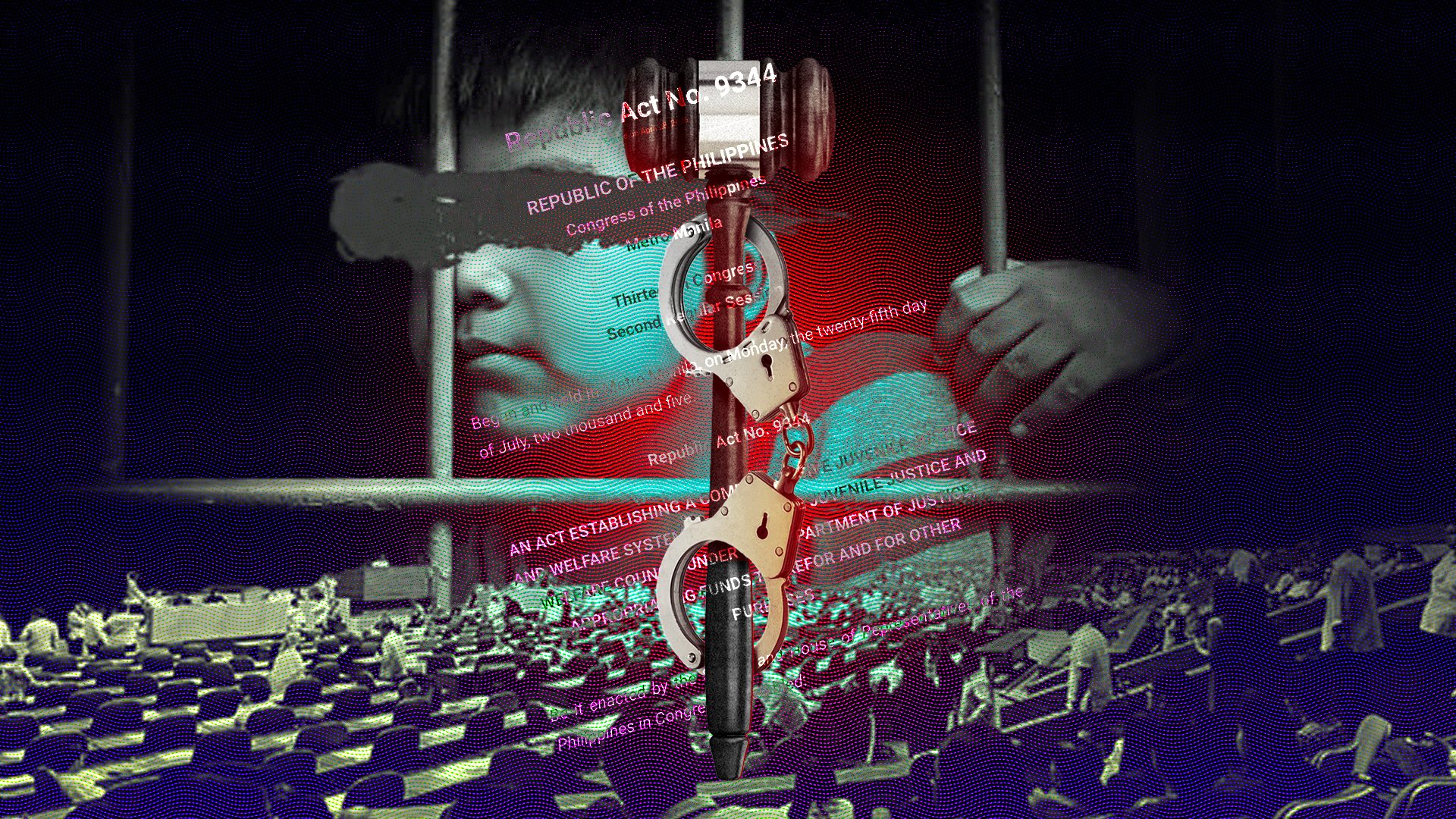

Republic Act No. 9344 or the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006 established the juvenile justice and welfare system in the Philippines. It laid down the rules in dealing with minors who committed offense, and the proper ways to address the concerns surrounding it.

Section 6 of the said law states the minimum age of criminal responsibility. A minor 15 years old or under is exempt from criminal liability, but shall be subjected to an intervention program. Usually, intervention programs include the involvement of authorities like the barangay or the Department of Social Welfare and Development.

How about minors over 15 years old, but under 18? This is where “discernment” comes in. The law said a minor who falls in this age bracket is exempt from both criminal liability and an intervention program, “unless he/she has acted with discernment.”

If the child is proven to have been acted with discernment, “such child shall be subjected to the appropriate proceedings in accordance” with the juvenile law.

The decades-old Revised Penal Code (RPC), which lists the definition of and punishment for criminal offenses, also defines what discernment is. In the People vs. Doquena case in 1939, the High Court further defined the term, in line with the RPC’s article 12(3):

“The discernment that constitutes an exception to the exemption from criminal liability of a minor under fifteen years of age but over nine, who commits an act prohibited by law, is his mental capacity to understand the difference between right and wrong,” the decision read.

The new SC ruling on discernment is important because it streamlines the guidelines for authorities involved in determining discernment – an important element in dealing with crimes involving minors. As pointed out by the High Court, the guidelines reiterated that there was a different approach when dealing with criminal offenses involving minors.

The origin case

The SC case stemmed from a case involving a minor, who was 17 years old at the time of the offense. The minor was charged with homicide before a Regional Trial Court (RTC) for the death of a person who testified against him.

According to the prosecution, the victim was a witness in the physical injuries complaint filed against the suspect by his friend. The victim testified that he saw the suspect hit his (victim’s) friend with a bucket inside a bar in Baguio City.

The next day, the parents saw their son with his face and eyes bloodied. He told his parents that the suspect struck his eyes. He sustained massive cerebral contusions and bleeding in the brain, “which may have been caused by any force or object hard enough to cause damage to the brain,” the decision read.

Although he was released from the hospital, the victim ended up in a vegetative state and remained bedridden for five years. He died on November 26, 2008. The suspect was found guilty of homicide by the RTC, and the Court of Appeals affirmed his conviction. The case reached the High Court after the appellate court’s decision.

In deciding the case, the SC affirmed that the minor committed the deadly act against the victim, and that the “proximate cause” of his death was the injury inflicted by the minor. With these, the elements of homicide were present. These were also the findings of the lower courts.

The High Court also ruled that the minor acted with discernment, a conclusion supported by the totality of the facts and circumstances of the crime.

“Ultimately, a careful consideration of all facts and circumstances, particularly the gruesome nature of the attack, the chosen time and place, the attempt to silence the victim who previously acted as a witness, and his very behavior and level of education, indicates that he acted with discernment. As gleaned from these facts, he committed the crime with an understanding of its depravity and consequences. Thus, CICL XXX is criminally liable for his act,” the SC decided.

The High Court said it found that the suspect mauled the victim with an object “hard enough to break a skull or shake a brain” – a finding supported by the brain injuries he suffered. The location of the wounds, as well as the deliberateness of their infliction, further showed the suspect’s discernment, said the SC.

Another instance showed the suspect’s “shrewdness,” according to the High Court. The minor perpetrated the attack at around 3 am with a companion. They waited for the victim to get home before hitting him, and then escaped after the incident.

“Further, CICL XXX’s (suspect) attack against the victim can be considered as an attempt to silence the latter or an act of retaliation for testifying against him in a separate mauling incident during the barangay proceedings,” the SC said.

The High Court added that the suspect’s own testimony revealed his awareness that he committed a wrongful act. The minor dropped out of school after receiving a warning that he should be careful, the SC said.

“Finally, at or near the time of the incident, CICL XXX was a second-year nursing student. Thus, his level of education shows that he had the capacity to discern that inflicting bodily harm upon AAA [the victim] was wrong, and it would likely result in his death,” the High Court added.

What happens now? The suspect will now be made to serve his sentence.

The SC noted that section 51 of the juvenile law, as well as the People vs. Jacinto case, state that “after conviction and upon order of the court, regardless of the age at the time of the promulgation of the judgment of conviction, (a minor) be made to serve his or her sentence, in lieu of confinement in a regular penal institution, in an agricultural camp and other training facilities that may be established, maintained, supervised, and controlled by the Bureau of Corrections, in coordination with the Department of Social Welfare and Development.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.