SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – In 2017, former president Fidel Ramos, a private citizen by then, laid out a vision for the Philippines to engage with a changing world. The position the country must take, he said, was not one that saw Filipinos “independent” but isolated, but one that sought genuine cooperation with allies, both old and new.

Interdependence and cooperation, Ramos long learned, is essential for any country to navigate and thrive in a world confronted with challenges bigger than itself. The worldview he held is one that continues to hang over the Philippines today, as it is forced to respond to growing threats, including climate change, rising food prices, unstable economic growth, and the consequences of war nearby.

“Let’s work with the world. No island is independent as of now, everybody is interdependent,” Ramos told Rappler in an interview. “It is an interdependent foreign policy that we must adopt, meaning, let’s go look for new allies and friends, but let us not discard our traditional, our loyal, our long-standing friends, partners, and allies, who have proven themselves to be helpful to the Philippines in war and peace.”

To those who knew him, Ramos himself was the embodiment of this ideal. Leading the Philippines after the late former president Corazon Aquino restored democracy, Ramos embarked on a mission to look out into the world for opportunities that could bring stability and prosperity into Filipinos’ lives, following the decades-long Martial Law under his cousin, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

At this historical juncture, Ramos himself made history. His six-year term from 1992 to 1998, saw the Philippines usher in a period of robust economic growth and political stability that lifted many Filipinos out of poverty and attracted billions in foreign investments. In doing so, Ramos told the New York Times in 1998: ”The Philippines has proven to be a good model in the developing world to demonstrate that democracy and development are compatible.”

Ramos died on Sunday, July 31. He was 94.

Mission-oriented

Looking back at Ramos’ inaugural speech in 1992, one could appreciate the clarity the former president had in laying out the goal for his administration: “This work of empowering the people, not only in their political lives, but also in their economic opportunities – I dedicate my presidency,” he said to loud applause.

It was this single-mindedness and resolve that Philippine Ambassador to the Hague Eduardo Malaya remembers most about the former president as a junior foreign service officer working in Malacañang at the time.

“I’ll never forget what he taught us: One should be clear about the mission one undertakes to implement. Have a vision for the country, and do not rest until you have achieved your mission,” Malaya recalled the advice of Ramos, whom he considered a mentor.

Ramos was tireless, too. Having a sense of urgency, the former president often took foreign trips – nearly every two months, Malaya recalled, which would leave officials preparing for his trips with an endless stream of work and assignments.

The frequency of Ramos’ trips, said Malaya, was the norm for many world leaders, but what set the former president apart was his “enthusiasm” and initiative to travel for work.

Determined to attract investments and bolster the Philippines’ economic ties with its allies, Ramos, referred to as the the country’s “No.1 salesman,” would express confidence on the ability of Filipinos to meet demands of the world.

He held on to this belief years later, saying in a 2003 interview with Leaders Magazine: “What also stands out is our (Filipino) spirit and our willingness to serve anywhere there is a need of some kind, and that should be seen as a special talent in this world of the 21st century.”

“His ‘Kaya natin ito!’ (We can do it!), was not only to us (Filipinos), but of the Philippines to the world,” Malaya said. To him, Ramos’ brand of diplomacy was one that was proactive, much like all other areas he oversaw as president.

On these foreign trips, Ramos “was always ready” to face his counterparts and “knew how to conduct himself” among his peers. Former Central Bank governor Jose Cuisia said much of the work Ramos did for visits abroad, he did even before he assumed the presidency.

“He was a workaholic,” Cuisia told Rappler. “Even before he assumed the presidency we were already conducting briefings for him on the economy and he would spend a lot of time with us just so he could understand…. He was very frank – he said, ‘I really don’t understand much of the economy, but I want to learn.’ So we were very happy of course, to give as much information as he needed.”

So keen was Ramos to have the Philippines become a “newly industrialized country” (NIC) – an economic buzzword at the time – that he was willing to go to as many countries as needed to boost the country’s profile as a potential hub for investments. “He said let me know where you need me, where you want me to go because he was willing to go all out; [to] as many countries as possible so he could encourage the businessmen to come to the Philippines,” Cuisia said.

Jojo Terencio, a close-in reporter for Ramos, later told the Philippine Star that Ramos expressed disappointment that the Philippines had not yet achieved NIC-status, but was optimistic the country could still achieve this. “We just need a road map, a long-term vision for the Philippines,” Terencio said, recalling Ramos’ words.

After his passing, Foreign Secretary Enrique Manalo paid tribute to Ramos as a “visionary.” The former president’s leadership, Manalo said, “steered our country to greater economic heights, with his opening of the Philippine economy and relentless campaigning for the country’s economic potential to the international community.”

Renewed business confidence in the Philippines, along with several economic policies initiated by Aquino, saw the economy expand from nearly 0% GDP growth in 1992 to some 5% in 1997, before falling once more in the aftermath of the Asian financial crisis. For this, the country under Ramos’ “Philippines 2000” had been referred to as a “tiger cub economy,” “Asia’s new darling,” and was ranked second to China in terms of the fastest-growing economies in the region.

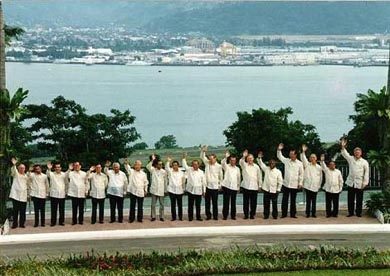

Ramos also successfully hosted former US president Bill Clinton and 17 other world leaders at the 1996 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit in Subic Bay, and oversaw the establishment of the Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines East ASEAN Growth Area (BIMP-EAGA), along with his counterparts in 1994.

“He took on the country’s highest job with the mind of an engineer and the discipline of a soldier,” Malaya said.

Raising standards

Ramos saw much of the world on his terms, too. After World War II, Ramos was accepted into the United States Military Academy in West Point and later pursued a graduate degree in Civil Engineering from the University of Illinois in 1951. He joined the Philippine Army upon returning to the Philippines.

As a young lieutenant, Ramos served in the Korean War as part of the Philippine Expeditionary Forces under the United Nations, and commanded a Philippine contingent in the Vietnam War. These experiences shaped the leader he was when he traveled and met the world.

“All of those came into play in the way he conducted himself with the usual dedication to work, honor, duty, country,” Malaya said.

As brother to two diplomats and son of long-time legislator, journalist, and former foreign secretary Narciso R. Ramos, Ramos was also steeped in the work of diplomacy, dialogue, and building consensus.

As the Philippines’ top diplomat, Ramos’ father was one of the five foreign ministers who signed the document that birthed the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Ramos would later hold the post as the Philippines’ representative to the Eminent Person’s Group on the ASEAN charter after his presidency.

In facing Chinese incursions into the disputed Spratly Islands and now-occupied Mischief Reef, Ramos likewise sought dialogue with China and simultaneously pushed for greater regional diplomacy in ASEAN to ease tensions.

A year after the tense incident which strained bilateral ties between Manila and Beijing, Chinese President Jiang Zemin arrived in the Philippines for the 1996 APEC Summit and a state visit. While the issue continued to be an irritant in relations, both presidents at the time agreed to “find ways” to foster “mutual trust” and step up ties “oriented towards the 21st century.”

At a dinner reception for Jiang during a Manila Bay cruise, Ramos turned up the charm. The two officials, at Ramos’ prodding, dueted Elvis Presley’s Love Me Tender. “Ramos and Jiang seemed like old friends…not the leaders of nations mired in territorial disputes. Jiang even affectionately touched Ramos’ arm in front of the other guests, after his first song,” recalled Mia Gonzalez, a veteran Palace reporter who covered Ramos up to Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III, and is now a senior editor at Rappler.

When one of the biggest diplomatic crises hit his administration with the execution of overseas Filipino worker Flor Contemplacion, Ramos wrote a letter to Singapore’s then-president Ong Teng Cheong seeking clemency for Contemplacion. His request was not granted, and Contemplacion was hanged in 1995, prompting the Philippines to downgrade its diplomatic ties.

Ties between the two countries normalized months later, but the incident pushed the Ramos administration to enact the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act, which raised the standards for overseas Filipinos’ welfare protection.

In reaching out beyond the Philippines, Ramos got the attention of the world. The late president earned multiple honors, including the French Legion of Honor, the Grand Cross, US Legion of Merit (Degree of Commander), as well as the Republic of Korea’s Cheonsu Medal, Order of National Security and Grand Order of Mugunghwa. Ramos would also be knighted by Queen Elizabeth II, receiving the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St. Michael and St. George in 1995.

“FVR made us look outward, dragged us out of our insularity. He kept reminding us, in his speeches, that the Philippines should compete in the regional and global arena,” wrote Rappler editor-at-large Marites Vitug.

Speaking during his 1996 State of the Nation Address, Ramos urged Filipinos to look to the future and draw strength from the country’s history: “Today our country calls us, not to die but to live for it…. If each of us pulled his or her weight, then we as a nation can be bound together not only by the common memory of our past sufferings but by the progress we can enjoy together.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[EDITORIAL] Marcos, bakit mo kasama ang buong barangay sa Davos?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/01/animated-marcos-davos-world-economic-forum-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.