SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Ahmed Alshantti remembers the year 2014 clearly. It was the year that he, as a medicine student, left a man to die.

Before the 2023 war, which has so far killed at least 14,000 in occupied Palestinian territories, the deadliest conflict between Israel and Palestine was 2014. It targeted the area of Shijaiyah in the Gaza Strip to hunt Hamas and was characterized by 50 days of unimpeded bombing by Israel on the enclave.

Alshantti said the Gazan health authorities needed all hands on deck – it did not matter whether you had no experience, or was just a student.

Alshantti resuscitated a man with a head injury, and “felt the man come back to life.” He was happy, he said, until he called the surgeon.

“He told me, ‘I’m sorry, Ahmed, it is full. I think we don’t have a choice, we need to leave him to die.’ And I was like quite shocked. This man has a family, has children. This is their dad left to die, because there is no one to do the operation, because it’s a very overcrowded emergency department,” Alshantti told Rappler in a Zoom interview he gave on Monday, November 27, from the United Kingdom where he is currently staying.

“I can see his heart beat go from 70 to 60 to 50, and then die. And then someone came in and covered him with the white clothes. And I can feel how the doctors are suffering right now from this experience. It’s very difficult as a doctor to see someone dying in front of you, and you are not able to do anything,” Alshantti said.

Choosing who to live “is a morally sensitive issue with a lot of guilt,” Gazan trauma doctor Mohammed Qandil said in an interview given to The New York Times about the latest war, “but we don’t think it’s our fault. We think it is the fault of the whole humankind who are unable to deliver safe, continuous medical aid to us.”

Alshantti is now 31 years old, a licensed doctor, but on what happened in 2014, he said, “I remember every moment of it, how this is just causing trauma for me now even as I am telling the story.”

They can name a few differences with their wars: the 1948 Nakba (catastrophe), the 2014 war that “has left a scar in my heart” as Alshantti described it, the 11-day Israeli offensive in 2021, and the 2023 war or the deadliest so far.

But one thing that makes 2023 most distinct is that the bloodbath is seen on instagram.

The war on Instagram

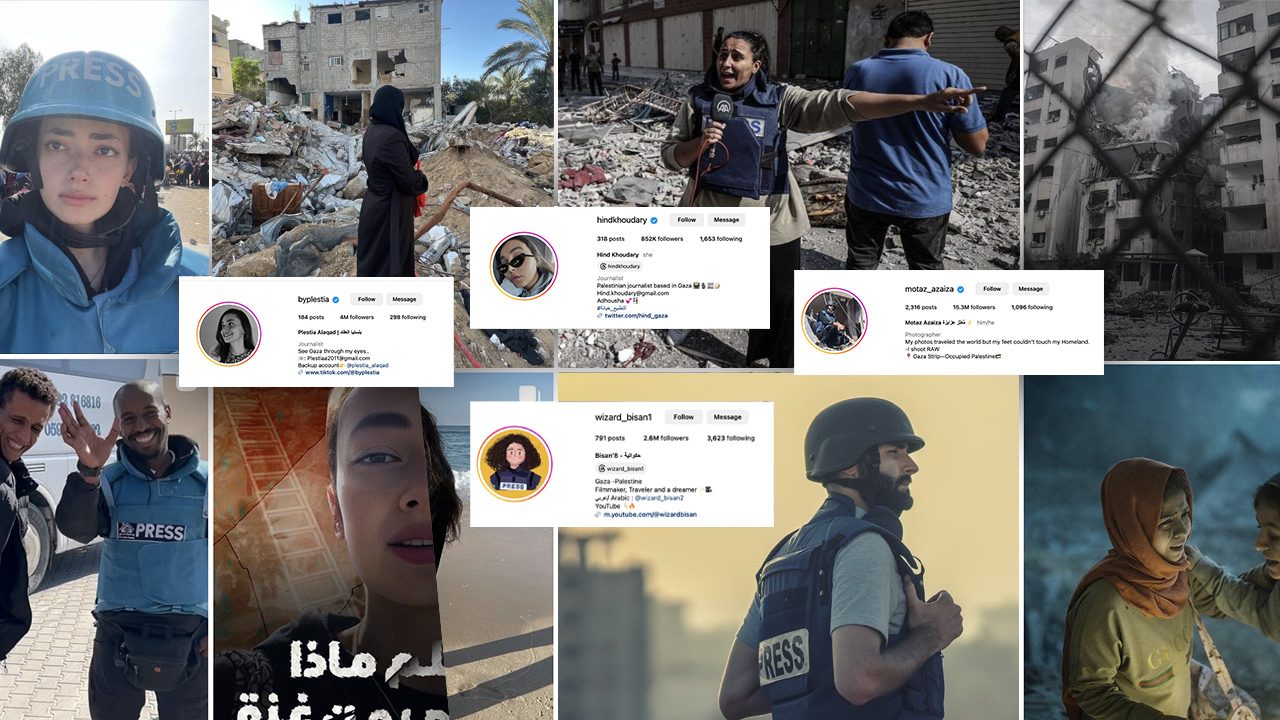

Alshantti will always have his memory of that fateful day in 2014. Journalist Motaz Azaiza, 24 years old, has a permanent record on Instagram of one of his worst days on earth: a bloodied baby shot in her forehead dumped into his arms as the car he was in sped away from the shelling.

Azaiza was shaking, but he kept rolling. It was the first week of the war, and from 25,000 followers as a photographer and digital content creator for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), Azaiza’s Instagram followers shot up to now 15.3 million, providing the world raw and uncensored images of the war, from photos, videos, and Instagram stories later compiled into permanently-accessible highlights.

With no outside journalists able to enter Gaza, Azaiza and the other young reporters there have become the world’s eyes on the ground. They are now experts in sneaking in internet signal to post their materials, what keywords to avoid Instagram’s bans, and on a few occasions, to escape death by only a few meters.

Bisan Owda left the frontside of the Al Shifa hospital two minutes before it was bombed. She was hysteric, crying out, but also managed to press record. These days, Owda begins her reels by saying, “Hi I am Bisan and I am still alive.”

“Look at Motaz, they go through the bombardment, they sacrifice their lives. So it’s very dangerous. I told you when I went to the hospital, there are drones in front of me, about to kill me. How about Motaz and other people? They know that they will be targeted but still they go and take pictures because they believe in you guys,” said Alshantti.

By “you,” Alshantti meant the people of the world, whom they hope would speak for them in lieu of their governments.

A thousand miles away in Manila, Amidah Macawadib joined on Saturday, November 25, one of the many peace marches for Palestine that have been happening around the country. Macawadib said she is not the protest-going type but was moved to join because “from October 7, I have been following Instagram, the real journalists inside Gaza.”

“I base on Instagram and you will see heartbreaking situations, in the first week it was okay for me, but the following week you wake up crying for the babies, mothers, it’s very painful to see,” Macawadib told Rappler.

The Philippines is the only Southeast Asian nation not to vote in favor of the United Nations resolution to call for a ceasefire last October. The New York director of UN Human Rights Commission has resigned over what he called the UN’s “failure” to respond to “text-book genocide” happening in Gaza.

The Gaza they know

While flying her drone in the completely flattened area in Khan Yunis in Southern Gaza Strip, Owda said: “People tell me this place was also destroyed in the 2014 and the 2021 wars, and they are used to rebuilding the neighborhoods. This, to me, is the meaning of being Palestinian, to get used to get destroyed and rebuild again.”

Alshantti said he has a warped definition of the word “normal,” because he would say life was “normal” in Gaza before the October 7 Hamas attack that prompted what is now a two-month bombardment by Israel.

“When I’m telling you about normal, for me, this means I have – this is the life I’m used to. For other people, it is inhumane, it is abnormal, it is not life. And I said to myself in hindsight, that this was hell I was living in. But unfortunately, people in Gaza are not aware of what is normal, what is the normal living standards of the planet,” said Alshantti.

Normal for them just means they were not being bombed without warning every day. But normal for them was Israeli forces calling the heads of households to say they should evacuate because their homes will be struck in a couple of minutes. Normal for them was looking up at the sky and listening for rockets that are another warning sign.

Normal for them was suffering in heat because there was not enough electricity supply to fuel their fans, but at least they had four-hour windows of power, and having more was already a miracle. Normal for them was going to work in a cart pulled by donkeys because only the very few elite can have a car – if they can even find the gas to fuel it. The image of Azaiza and fellow journalists on a donkey cart was normal, if only it were not a desperate sojourn to flee South, reminiscent of the 1948 Nakba.

Normal for them was to be a little less insecure for their life.

On Instagram these days, normal is when the journalists are not running away from airstrikes, or running toward lifeless bodies in the rubble. Normal is when Azaiza took a shower finally, albeit in the dark; normal is when Owda got a cup-full of water from a firetruck so she can wash her face; normal is when Hind Khoudary managed to build a firewood so they could finally cook bread; and normal is when Plestia Alaqad’s cousins got enough peace and quiet to make bracelets.

“On the negative side, they are making bracelets with everyone’s names on it in case any family member dies,” she wrote on her Instagram which has now four million followers.

‘She did not want to leave’

Alshantti said that as soon as news of the Hamas attack broke, people in Gaza “were very terrified, were very worried and extremely anxious.”

Alshantti’s family somehow received warning that their home was going to be struck, so they evacuated in the middle of the night to a relative’s house. When they arrived, the relative got fair warning his home would be struck next.

“Can you imagine? So my family was asking themselves where to go, where to go? At that time, Israel said to flee south. They went south, all of them. They left my sister, because she refused to leave. Because she said that if I leave, I will not come back, because Israel is known for ethnic cleansing,” said Alshantti.

The next couple of days were more nightmares for his family, because a bomb hit the neighbor’s house in the South where they were staying. Alshantti’s father was injured in his arms, and his brother-in-law in his head. They took shelter in a UNRWA school where people competed for the very little resources.

“My brother told me he was waiting seven hours to get bread, just two to three breads for 50 people, and then seven hours to charge the electricity for their phones. So they spent about 14 hours just to get water and a bread for a family 50,” said Alshantti.

His sister still refuses to leave the North of Gaza where the bombing is concentrated. Supply is running out there, and communication is much worse than in the South. To access the internet now requires being clever enough to find a way to connect to the Israeli network, whether that’s by e-sim or any other method.

Not that it’s easy to leave anyway, as the Rafah border in Egypt was never freely accessible even in “normal times,” but Gazans find it very hard to leave home because they know that once they do, they had conceded their land, and they yield an inch of their 75-year struggle for their freedom.

Alshantti’s grandparents were born and raised in what is now Israel. His sister told him she does not want to experience ethnic cleansing twice. But even if they wanted to leave, it’s not easy, too. Alshantti said getting visas is not the issue, but how to actually go through the borders, whether that’s through the Egypt crossing or the Israeli crossing. Alshantti said he has given up opportunities to go abroad before because he could not cross the border.

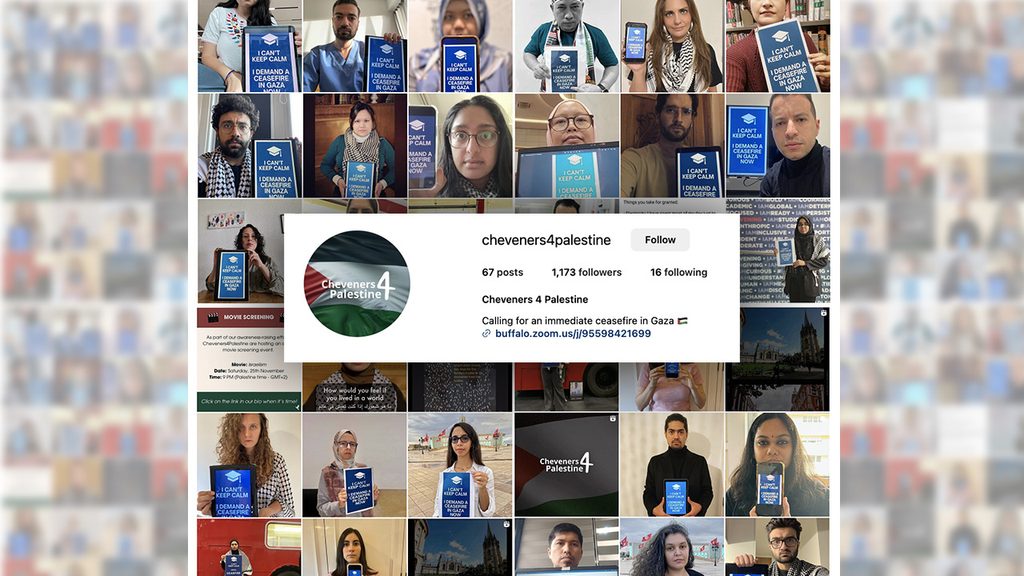

The only way he reached the UK was because in 2019, he was chosen for a British Chevening scholarship, a secure pathway for Palestinians to squeeze through the strict borders of Israel, an ally of the UK. Alshantti is now an obstetric and gynecology doctor in the UK.

Alshantti said to go back is also difficult – a six-hour journey by land from Egypt would take them three days because of the checkpoints.

“I came back to Gaza last year, and I said about two days during my travel sleeping on the floors of the bus or the outside, because there’s no way you can go outside the bus,” said Alshantti.

Alshantti has lost a friend, fellow doctor and also a Chevening scholar Maisara Alrayyes who died in an Israeli airstrike on November 5. His friends and other witnesses said his two brothers were also killed after searching for Alrayyes in the rubble.

Alshantti said he and other Palestinian scholars were just talking to him on their Whatsapp group three days before he was killed. Alrayyes had told him, “I am good, Ahmed.” Then he was gone.

“This war changed my life, to be honest, it changed my life. And emotionally, I’ve been devastated about what is happening, and I was not able to do anything in my life,” said Alshantti.

Winter is coming

Winter is coming to Gaza, and they are beginning to feel cold. Coats have gotten insanely expensive, so Gazans are hoping that the humanitarian pauses will allow them to prepare. The electricity has also returned.

“My family has been able to send me videos of their youngsters, like six years old, dancing in the house because they have seen light. For the last 40 days they haven’t seen light, they’ve been living in candles or no lights whatsoever,” said Alshantti.

“My brother told me today that it is the first time he’s calling me from the center of the street, from the middle of the streets, that he’s not afraid for his life,” he said.

But humanitarian groups are in consensus that no less than a ceasefire is urgently needed. “While it is a welcome step in the right direction, it cannot replace a ceasefire, first and foremost there is no safe space in Gaza, there [are] insufficient goods in Gaza that will allow us to mount an effective response,” said Jason Lee, country director of Save the Children Palestine in a press briefing on November 22.

The “dystopian reality,” as Doctors without Borders USA chief Avril Benoît called it, has prompted the usually neutral groups to explicitly call for a ceasefire.

Alshantti and his fellow Chevening scholars, current and past, have resorted to provocative methods to call for a ceasefire too, possibly risking their standings as beneficiaries of the flagship British diplomatic program. The UK Parliament has still so far rejected a motion for ceasefire.

Although Instagram is the main space, the platform which is also owned by Meta has some restrictions too. Video of Hamas releasing hostages to an aid worker, filmed from close range and with intimate shots of the seemingly pleasant last look and talks between hostage and captors, is removed by Instagram within minutes of posting.

Instagram says it violates community rules on praising terrorism (Hamas is designated as terrorists by Western governments). Influencers supporting Palestine play a cat-and-mouse chase with Instagram, flooding the comments section with mundane phrases like “Get ready with me” to preserve the post as long as possible.

“We know this in advance and we were prepared for it and people have taught us in Gaza how to deal with this, how to take different ways of posting and not get removed,” said Alshantti.

They keep at it because Alshantti said, “The tide is turning, and I need to be a part of it.”

“Seeing young people, not Palestinians, advocating for our cause. Oh my God, I’ve never seen this. I’ve been in 2014, all these wars, in 2021. This means in the next five or 10 years those people will continue talking and advocating for us,” Alshantti said.

“I believe we are more close to our freedom from the occupation, more than ever,” Alshantti said.

“What more to show?” wrote journalist Azaiza on his photo of a dead young bloodied girl. “Patience is the only weapon we have,” he said. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Unjust wars and a just peace](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/tl-unjust-war-just-peace03262024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.