SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

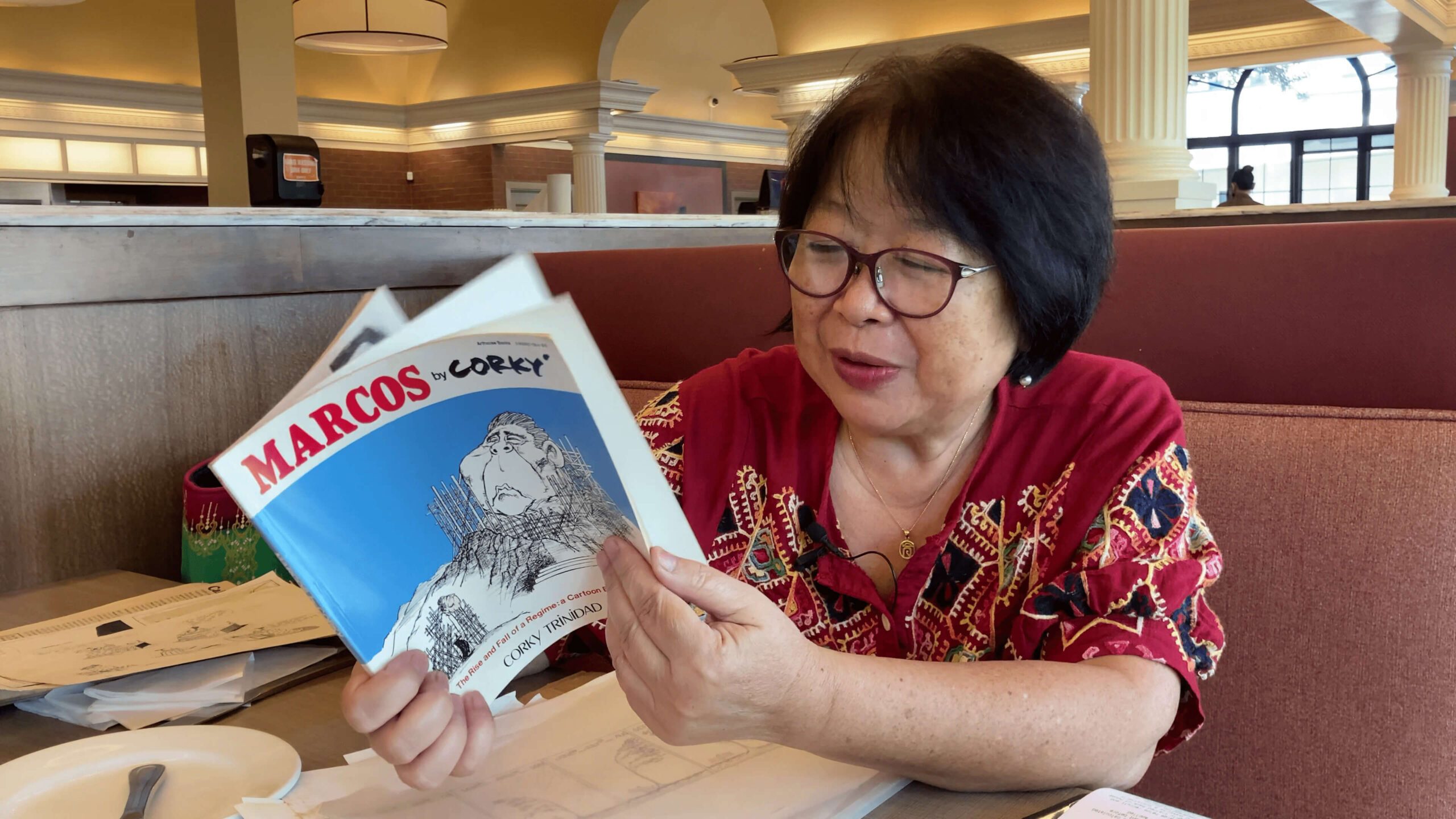

HAWAII, USA – When Ferdinand Marcos Jr. won the Philippine presidency in 2022, a retired architect in Hawaii who drew political cartoons on the side during the years of the Marcos dictatorship knew she had to dig up old files.

Rose Churma called families of her departed contemporaries Dick Adair and Corky Trinidad, and asked them if they could provide her with the most compelling artwork made by their husbands. The spouses said yes.

In October that year, Churma helped organize an exhibit on the political cartoons at the Hawaii State Library. The timing coincided with the celebration of the Filipino American History Month, and came weeks after the 50th anniversary of the declaration of Martial Law in the Philippines.

“We need to ensure that the children of rabid Marcos fans here understand why we are protesting, why we are against the return of the Marcoses,” Churma told Rappler during this reporter’s visit to Honolulu in mid-November this year, for Marcos’ working visit and homecoming to the island state.

Introduction to cartooning

Churma didn’t really intend to enter the world of editorial cartooning until she read Newsweek‘s interview with then-first lady Imelda Marcos in 1982. The article, she said, showed that Imelda was tone-deaf.

“She said there, ‘I must confess that once upon a time, his family and my family were oligarchs. But we are reformed oligarchs.’ I was like, ‘Oh my God, what is she saying?'” she recalled. “The only way that I could do something was actually share my feelings of frustration through cartoons.”

She sent her output to Ka Huliau, an alternative publication in Honolulu, that liked her work and began publishing her cartoons more often.

“My cartoon column was named Sand in the Eye, because in my mind, even a grain of sand in your eye can turn into pearls,” Churma said.

Marcoses and Hawaii

The Marcoses have a deep history with the state of Hawaii. Even before becoming the family’s home away from home, the first couple frequented the island state at the peak of their power.

They always received a warm welcome – the local Ilocano community adored them, and officials from the United States, a close diplomatic ally of the Philippines, treated them as VIPs.

“He apparently had a lot of godchildren here. So whenever he came, he had a ready-made audience,” said John Wickett, a retired American activist who was a staunch advocate of Filipino causes during his prime.

When the conjugal dictatorship came crashing down due to the 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution, the Marcoses fled to Hawaii. While anger towards the Marcoses was the prevailing sentiment in the Philippines at the time, the mood in Hawaii was quite different.

A significant portion of the Filipino diaspora in the US state felt that the Marcoses were wronged, falling victim to the cruel world of Philippine politics.

“There were a lot of pots and pans, you know, banging and protests. But the community here was divided. There were a lot of people who supported Marcos also,” said Richard Rothschiller, a labor organizer in Hawaii.

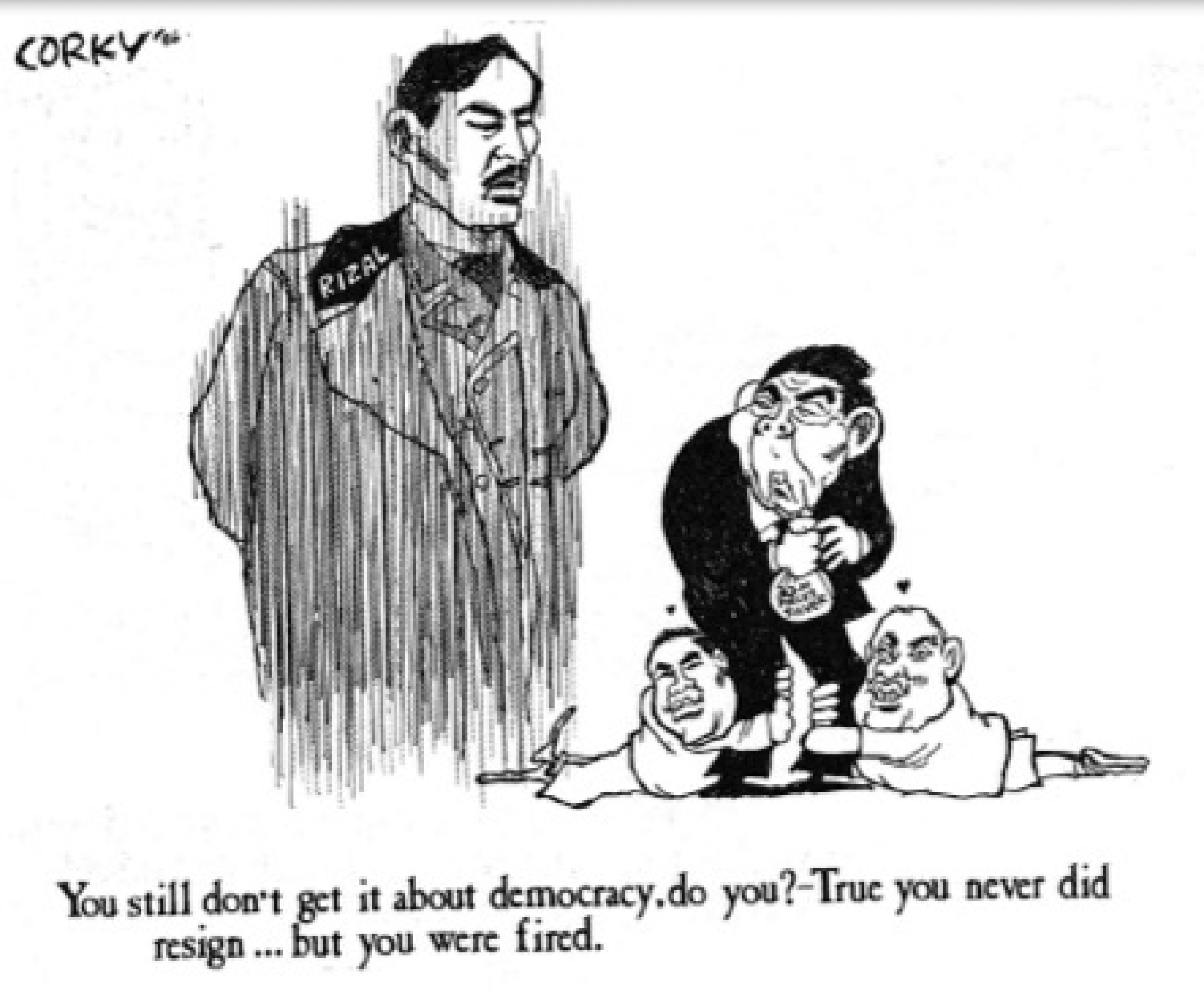

The presence of an ousted dictator from a developing country in Hawaii hogged the headlines of the local papers at the time. Cartoons on the editorial section of Honolulu broadsheets featured pushback on the Marcos family’s refuge in the island state.

Preserving the cartoons

Among those who received Churma’s phone call in 2022 was Margot Adair, a teacher in Hawaii who migrated to the US in the 1970s. She is the widow of the late Dick Adair, the longtime American cartoonist for the Honolulu Advertiser.

Adair and Corky Trinidad, a Filipino cartoonist from the Honolulu Star-Bulletin who died in 2009, were the major newspaper cartoonists in the Hawaii capital in the 1980s.

“Rose asked me, ‘Can Dick’s cartoons be included?’ And I said, ‘Of course.’ We were very much part of the anti-Marcos feeling when they were here,” Margot told Rappler.

“Rose also asked me, ‘Can you ask Hana, [Corky’s] wife, if we can use Corky’s cartoons also?’ So between the permission of Hana and myself, we worked to see what cartoons could be used for the exhibit,” Margot added.

Margot admired not only the sheer talent and artistry of her husband, but also the biting commentary that each of his cartoons offered.

“My husband was known for his acidic humor. And so a lot of his cartoons were very sharp, but very witty as well,” she said. “He really poked fun at Imelda and her butterfly green terno. And that became the standing joke here.”

It was a tense period in Hawaii, and the Adairs, being anti-Marcos, were hated by some members of the Filipino community. Margot still remembered the harassing phone calls she received at home, their car tires that were mysteriously flattened, and protests by pro-Marcos people outside the building where her husband worked.

Adair’s employer was able to digitally archive his old cartoons, and Churma made some calls to retrieve them in time for the 2022 exhibit. Margot, however, no longer possessed original hard copies of many of her late husband’s drawings after he asked her to burn them before he succumbed to his illness in 2017.

She wished she hadn’t done so. “I always regret that, but I wanted to respect his wishes, so I got rid of his cartoons.”

She believes that saving her husband’s artwork has become important now more than ever.

“His cartoons should be preserved. Not only his cartoons, but anything related to telling the truth about that time – those times in history that have to be preserved, so that we don’t revise history,” Margot said.

Marcos country

The Filipino electorate in Hawaii delivered a Marcos victory in 2022. Over 80% of registered voters there wanted him to be president, crushing opposition forces who campaigned for his closest rival, former vice president Leni Robredo.

Since the elections, Senator Imee Marcos and her brother marked their return to Hawaii more than three decades since they lived in exile there. Excited crowds greeted them during separate visits in October and November 2023, respectively.

“If not because of you, maybe the Marcos family would have been no more,” a nostalgic Marcos said to his enthusiastic audience upon his arrival.

For his supporters, the atrocities of the family – from the human rights abuses during the Martial Law years to the well-documented cases of graft and corruption – are a distant memory.

“Those who were here before 1986, they had nothing bad to say, nothing negative about the Marcoses. The younger generation, meanwhile, didn’t experience the Marcos Sr. era. It’s history to them, not experiential,” Oahu Filipino Community Council president Raymond Sebastian, a pro-Marcos supporter who participated in his 2022 campaign, told Rappler.

“I wasn’t able to relate [to the stories of Martial Law]. If they will say, it’s true and it happened, I won’t deny it, I will respect it. But you should not also force your beliefs on me. Let’s find a common ground where we can work together,” he added.

Small opposition

The pushback against the Marcoses in Hawaii comes in trickles, and is now led by a new generation of Filipinos who moved to the US relatively recently, guided by an older generation of activists who are ready to turn over the reins.

Groups such as Anakbayan and the Hawaii Filipinos for Truth, Justice, and Democracy have conducted film screenings of Martial Law-themed movies Dekada 70 and Katips, in an effort to introduce the brutalities of the regime to the younger segment of the Filipino community.

“We’ve been holding events – regular meetings, gatherings at the park which are also like a show of force, and education campaigns, especially for the youth,” said Arcy Imasa, a Filipino physician who co-chairs the Hawaii Filipinos for Truth, Justice, and Democracy.

For Churma, protesting through art is an apt reminder of the gains the community has made over the years, despite the crucial setback dealt by a Marcos presidency.

“It’s hard to make sense of Marcos’ return to Hawaii. But I think it’s really about the importance of bringing up a generation of critical thinkers not only in the Philippines, but actually here,” she said.

The opposition in Hawaii is minuscule, but they are there, and they are a haunting reminder that even in a strong Marcos bailiwick, the concept of a “solid North” is constantly being challenged by a vocal minority.

“No aloha for Marcos,” the small, outnumbered group said in the 1980s.

That protest tagline remains the same today.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Newspoint] A fighting presence](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-a-fighting-presence.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=441px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Closer Look] ‘Join Marcos, avert Duterte’ and the danger of expediency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-trillanes-duterte-expediency-june-29-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.