SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

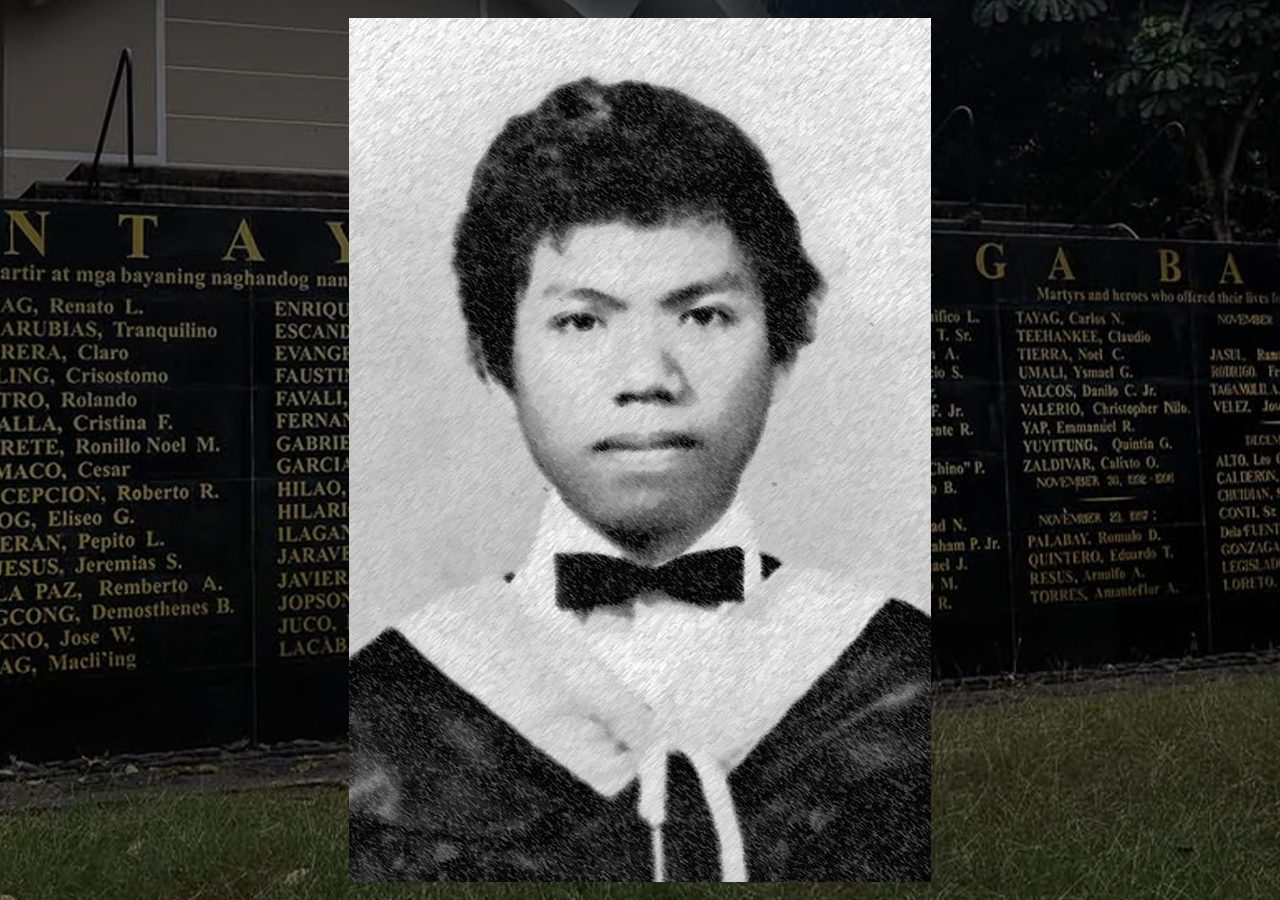

MANILA, Philippines – Church youth leader Romeo Crismo was abducted by suspected members of the military during Martial Law on August 12, 1980.

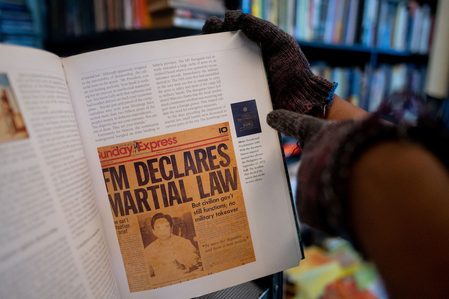

A lot has happened in the more than four decades since he disappeared: The restoration of Philippine democracy following the ouster of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, the country’s descent again into a dark period of violence and impunity under the former president Rodrigo Duterte, and in what previously existed only in the wildest dreams of many, another Marcos administration.

It was an overwhelming election period that saw 31.63 million Filipinos voting for President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the only son and namesake of the man responsible for deaths, torture, and disappearances of thousands from Romeo’s generation.

The years preceding the victory of yet another Marcos were marred by blatant efforts to rewrite history, tapping social media to spread lies and bury what really happened during the Martial Law years.

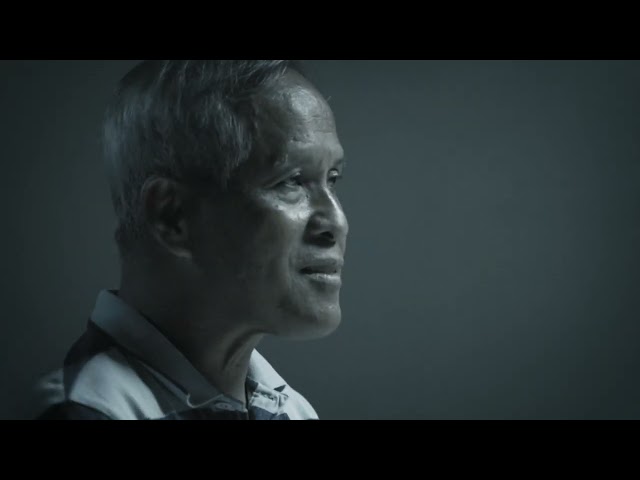

For Louie Crismo, Romeo’s brother, it was like rubbing salt on a wound that wouldn’t heal.

“Wala pa nga kaming hustisyang natatanggap tapos ang malala pa ay pilit gustong tabunan ang alaala at mga nangyari sa aming mga mahal sa buhay,” he told Rappler in an interview.

“Binabale-wala iyong ginawa at sakripisyo ng mga pinatay at mga nawawala pa, pati na ang mga martyr at bayani noong Martial Law,” Louie added.

(What’s worse is that we really haven’t gotten justice and here they are trying to bury the memories and what happened to our loved ones. They take for granted and dismiss the sacrifice of those killed and still missing, and the martyrs and heroes of Martial Law.)

Growing up religious

Romeo Crismo was everything a family could hope for in a son and a brother.

He was the eldest among seven children of devout Methodists. Sunday school and bible studies were staples during their childhood in Quirino province. But Romeo, the ever curious boy, did not limit himself to reading the bible but also explored history and politics.

In high school, he became active in the student council and was eventually elected president of the study body.

“Noong bata pa lamang kami makikita mo na talaga na mahilig siya magbasa ng mga librong tungkol sa mga isyu sa lipunan,” Louie, his brother, recalled.

Romeo and his peers came of age during a period where there was no blatant effort to draw a line between their religious beliefs and what was happening in the Philippines. For them, religion did not exist in a vacuum, or was excluded from daily realities of life.

Romeo became heavily involved in ecumenical organizations, including the National United Methodist Youth Fellowship of the Philippines (NUMYFP) and the Student Christian Movement of the Philippines.

He took on national leadership positions, including being the first executive secretary of NUMYFP. He worked in programs that cater to people beyond their membership, especially in the poorest communities.

“Hindi pinag-uusapan ang paghiwalay ng relihiyon sa politika kasi hindi naman dapat ganoon,” Louie said.

“Kung Kristiyano ka, ibig sabihin, gusto mo rin magkaroon ng environment na merong justice, peace, pagkakapantay-pantay,” he added.

(We didn’t talk about how religion is separate from politics because it shouldn’t be that way. If you’re a Christian, you also yearn for an environment where there is justice, peace, and equality.)

Romeo juggled his church involvement with tasks of a campus journalist for the official publication of St. Mary’s College in Nueva Vizcaya, where he was studying to be an accountant. According to his profile published on the Bantayog ng mga Bayani website, he wanted to be a lawyer but took up accountancy upon the wishes of his father.

His wife Phebe Gamata Crismo, whom he met during a church youth conference during their teens, recalled that a friend described Romeo as “a young man in a hurry.”

“He was always working, cramming as if there was no tomorrow, maybe he knew he did not have long to live,” she said during a speech delivered in 2003.

Romeo became an accountant in 1977 and went on to work for the government, but not without always thinking how he could better contribute to the rising opposition against the Marcos dictatorship. He later on became involved in organizing opposition forces with members of his church organizations.

His family knew this work was dangerous, but saw how vital it was.

“Hindi naman against ang family pero naalala ko, dahil iyong father ko ay nasa gobyerno, alam naman niya na hindi talaga malaya magsalita,” Louie, an activist himself, said.

“Pero hindi naman pinipigilan, marami lang paalala lang na mag-ingat,” he added.

(My family wasn’t against it, and since my father worked in government, he knew we weren’t really free to express our opinions. But we were not prevented from being involved in mass movements, we were just reminded to be careful.)

The abduction and disappearance of Romeo

Romeo moved to Tuguegarao City in 1980 and started teaching accountancy classes in St. Louis College. In March of that year, he married Phebe.

Barely five months after their wedding, Romeo disappeared.

Romeo, then only 24 years old, was last seen by his students just outside the campus on August 12, 1980. It was supposed to be just another day where he would go to class, teach, and go back home.

“Nagpuntahan na ang mga estudyante sa kanilang classroom kasi nga nakita nila na papasok na siya sa gate pero after mga ilang minuto, hindi naman na siya dumating, kaya nagtaka na sila,” Louie recalled.

(The students already headed to their classroom because they saw my brother near the gate. But after a few minutes, he still didn’t arrive, so they were really puzzled.)

His family would later find out that there were students who saw suspected military agents in plainclothes forcibly taking Romeo and placing him in a car. He was never to be seen again.

Louie and his two other siblings were studying at the Central Luzon State University in Nueva Ecija when Romeo disappeared. They only knew of what happened when their parents visited them a week after the incident.

“Bilang aktibista noon, sabi ko, heto na, nangyari na, kasi alam ko naman na ang nangyayari sa mga katulad namin ay either puwede ka makulong, mapatay, o matorture,” he said.

“Ang mga kapatid ko umiiyak na sila at ako siyempre umiyak at nalungkot kasi sabi ng parents ko noon, more than a week na silang naghahanap bago sila pumunta sa amin para dalhin ang balita,” Louie added.

(As an activist, I told myself that it had actually happened because I knew about what happens to the likes of us – you’re either detained, killed, or tortured. My siblings and I were crying and were saddened, especially when my parents said that they had already been looking for my brother for more than a week before they went to us to deliver the news.)

What followed were years of futile searching for Romeo. His wife and parents would go to military camps in Isabela and Cagayan almost every day, relentlessly questioning soldiers about him.

They followed information that led to nowhere. In one case, Romeo’s family got a lead that he was allegedly buried in a university campus, but the source and other details remained elusive so they had to drop the search.

The family even wrote letters to the then-first lady Imelda Marcos and then-defense minister Juan Ponce Enrile, according to Louie.

“Ang dami ring nakapilang mga pamilya na naghahanap ng kanilang mga mahal sa buhay (There were a lot of families also looking for their loved ones),” he said.

Life-long quest to find Romeo

Romeo is only one of the thousands who disappeared during Martial Law.

They came from all walks of life bound by the desire to end military rule and restore democracy to the Philippines. They were labor leaders, lay people, students, doctors, priests, nuns, and writers, but they were also fathers, mothers, sons, daughters, siblings, and life partners.

In 1985, nine families, including the Crismo family led by Phebe, moved to create Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearances (FIND), one of the foremost organizations that have documented the cases of the disappeared and have lobbied for justice. Romeo’s brother Louie now serves as the groups’ co-chairperson.

Data from FIND show that there were 1,022 reported victims of enforced disappearances under the Marcos dictatorship. The group was able to document and closely follow 977 such cases within this period. Out of this number, 204 surfaced alive while 133 were found dead. At least 640 are still missing.

The Crismo family may have ceased going to military camps on a daily basis, but it doesn’t mean that they have ended their quest to find Romeo, who would have turned 67 years old this December.

At the very least, they want to give him a decent burial – if he is indeed dead – for closure.

“Habang-buhay ka maghahanap talaga kasi hindi naman namin alam talaga kung anong nangyari sa kanya,” Louie said. “Hindi naman sa titigil ang buhay namin kasi magpapatuloy naman kami pero mananatiling may kulang.”

(We’ll forever be looking for him because we don’t know what really happened to him. Our lives did not stop, we continued living, but there will always be something missing.)

Rome’s father died in 1996 – 16 years since his disappearance. His mother, meanwhile, spent 35 years longing for her son until her death in 2015.

Louie recently found out from a sibling that their mother, at her old age, often went out of the house in the hopes of finding Romeo.

“Kung saan saan nagpupunta tapos sinusundan na lang nila, hindi na niya alam kasi ang kanyang ginagawa,” he said.

“Masakit talaga sa kanya kahit na hindi namin pinag-uusapan masyado kasi tahimik lang siya, pero laging nakapatong ang kanyang kamay sa dibdib, may kinikimkim talaga,” Louie added.

(She would go to random places and my siblings would just follow her because she didn’t know what she’s doing anymore. I know that she really suffered a lot even if we don’t talk about it, since she’s usually quiet, but she keeps her hand over her chest, like she has this pain kept inside her.)

No amount of disinformation and massive propaganda could erase the lived experiences of the Crismo family in the aftermath of the disappearance of Romeo. But the distinct and relentless efforts of a widespread and well-funded machinery push other people to forget the sacrifices of the desaparecidos, or the disappeared.

On social media, particularly TikTok, people tag Martial Law martyrs as communist sympathizers, if not communist insurgents themselves. They say they deserved what happened to them for rising against the Marcos dictatorship.

Louie Crismo wants Filipinos, especially the youth, to reject efforts of the government to forget what happened during the country’s darkest period. He wants them to be more discerning and critical because behind every Martial Law victim targeted by the whitewashing and smear campaigns are families still reeling from the loss of their loved ones.

“Puwede ka mag-move forward pero ibang connotation iyong sinasabi nila na mag-move on, na parang kalimutan na natin iyong nangyari sa aking kapatid at sa libo-libo pang iba,” Louie said.

“Sabi nila past is past daw, pero paano mangyayari iyon kung hanggang ngayon walang hustisya?” he added.

(We can move forward, but not move on because that’s a different connotation. It’s like they want us to forget what happened to our siblings and to thousands of others. They say the past is past, but how could that be if until now there’s still no justice?) – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Closer Look] ‘Join Marcos, avert Duterte’ and the danger of expediency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-trillanes-duterte-expediency-june-29-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] A Freedom Week joke](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/20240614-Filipino-Week-joke-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Raised on radio](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/raised-on-radio.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=396px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] Marcos: A flat response, a missed opportunity](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcos-flat-response-april-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.