SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] What Chernobyl could have taught us, but hasn’t been allowed to](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/04/chernobyl-doll-ukraine-children-hospital.jpg)

The following is the 26th in a series of excerpts from Kelvin Rodolfo’s ongoing book project “Tilting at the Monster of Morong: Forays Against the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant and Global Nuclear Energy.“

On March 4, 2022 a Russian rocket hit a Ukrainian nuclear plant. The damage was minor, but the world panicked, sharply reminded of its worst nuclear disaster and our collective vulnerability to such accidents.

Five days later, a much more serious threat: power to pump cooling water was lost to Chernobyl pools containing 20,000 spent-fuel assemblies, 22 years after their NPPs were closed. Keep posted…

On April 26, 1986 design flaws and human errors made Ukraine’s Chernobyl Reactor 4 undergo a nuclear chain-reaction, causing an explosion.

Nuclear proponents stress the difference between reactors and bombs. But that day, Reactor 4 became a bomb – small and inefficient as nuclear weapons go, but a bomb nevertheless.

Fifty tons of pulverized nuclear fuel blew high into the atmosphere. Winds spread Uranium dioxide, Iodine 131, Plutonium 239, Neptunium 139, Cesium 137, Strontium 90, and other radioactive isotopes over Belarus, the Baltic republics, and over much of Europe beyond the USSR.

The USSR, notorious for its contempt for truth and for the value of human life, declared the catastrophe over after only 10 days, even though radioactive gases poured out for another week. This, while more than a half million emergency clean-up personnel exposed to the radiation worked tirelessly to contain the damage, some knowingly sacrificing their lives, heroism far exceeding the depths of their government’s cynicism.

Gregori Medvedev, Chernobyl’s chief engineer during its construction in 1970 was in Moscow, in charge of nuclear power plant construction in the Soviet Union. A few days after the explosion he headed an official investigation sent to Chernobyl.

Medvedev’s 1991 book The Truth About Chernobyl describes shocking administrative and operational negligence, nonexistent precautions, an unstable reactor design, inadequately-trained operating staff, and the badly-planned and botched experiment during reactor shutdown that triggered the disaster.

And denial: the plant director wouldn’t admit the reactor was destroyed even after shown pieces of it scattered about. Moscow delayed timely evacuations to prevent panic, then gave people only 50 minutes to get on evacuation buses.

From the beginning, authorities have denied the seriousness of the disaster and its effects. Prize-winning historian Kate Brown has documented in excruciating detail “how international regulatory agencies and research institutes expended a great deal of effort not to know about the effects of the Chernobyl accident, to limit research and to contain judgements…” She describes how “…scientists engaged in a broad continuum of ignorance-producing activities.”

But we, the general public, feed that dishonesty with our thirst “for a science that supplies unequivocal and precise answers, even when mythical,” as Brown says.

Our last foray ended with WHA 12.40, the 1959 agreement between the World Health Organization and the International Atomic Energy Agency that gave IAEA veto and censorship power over any WHO action that might relate to nuclear power or nuclear weapons. IAEA has exercised this power ever after Chernobyl . It prevented publication of the full proceedings of major conference on its health impacts held in Geneva in 1995, and in Kiev in 2001.

In 2006 WHO, IAEA, and the United Nations Development Program jointly issued a press release entitled “Chernobyl: the true scale of the accident.” It reported “[a]bout 4000 cases of thyroid cancer, mainly in children and adolescents at the time of the accident.” This certainty denied the actual data, because casualties were still accumulating. The idea was to reassure, not to explore the uncertain future. But in 2016 WHO reluctantly quintupled the “true scale” to 20,000 cases.

How slavishly the United Nations obeys IAEA is displayed by its United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR). See for yourself; access its latest pronouncement on Chernobyl, updated on 6 April 2021: www.unscear.org/unscear/en/chernobyl.html. Under the heading of “Health Effects”:

“Of 600 workers present on the site during the [accident], 134 received high doses… and suffered from radiation sickness. Of these, 28 died in the first three months and another 19 died in 1987-2004 of various causes not necessarily associated with radiation exposure. In addition, according to the UNSCEAR 2008 Report, the majority of the 530,000 registered recovery operation workers received [minor] doses…between 1986 and 1990. That cohort is still at potential risk of late consequences such as cancer and other diseases and their health will be followed closely [emphasis mine].”

What? “…their health will be followed closely?” It bases these claims on their own 13-year old data!

We saw in Foray 26 how disciplined studies of the health impacts of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings began in 1946 and continue to this day. More than half a century after the bombs, the Radiation Effects Research Foundation in Japan is still documenting deaths from leukemia, thyroid, breast, lung, colon, and stomach cancers. Chernobyl was only 36 years ago. The Chernobyl radiation exposure is also very different and much more complicated than the virtually instantaneous exposure from the atomic bombs in Japan. Its fallout, spread widely over much of Europe, will linger for years.

Another tactic to minimize the effects of the disaster is to limit analyses of its effects to Belarus, Russia, and the Ukraine, the three most contaminated countries in this map.

But huge areas of Europe far beyond those three countries received lesser, but still worrisome Chernobyl radioactivity. In the following map, the area of this first one is the small red polygon:

Our next foray will explore “Linear No Threshold (LNT),” which says that there is no “safe” level of radiation. After all the USSR and IAEA efforts to hide, obscure, or destroy data and to discourage Chernobyl research, the illnesses and deaths will never be known for sure. Estimates vary from WHO’s minimized 4,000 to as many as 1,031,500.

If you breathe in, eat, or drink radioactive isotopes and they decay inside your body, the radiation inflicts your organs and tissues with different doses, and they respond differently, some more slowly than others. With or without disciplined and unbiased studies, the effects will continue to appear over time.

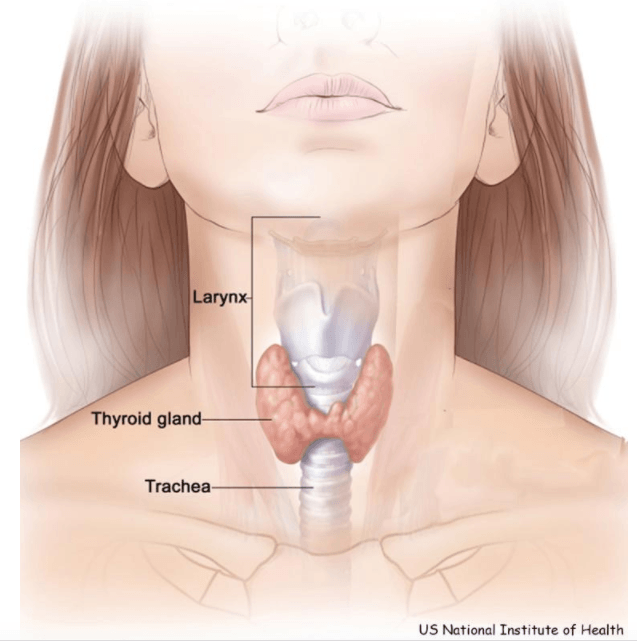

Thyroid cancer has been Chernobyl’s most prominent effect. The thyroid gland, just below the voice box, makes thyroxine, the hormone that governs how fast the body changes food into energy. A key ingredient of thyroxine is Iodine 127, the only natural isotope of iodine that we get from seafood and milk. Little wonder children are most affected.

Thyroids readily store Chernobyl’s radioactive Iodine 131, which decays into Xenon 131 by beta and gamma emissions that damage DNA and other genetic material. By 1990, children and teenagers who were in Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia during the first few weeks after the disaster started developing thyroid cancer. By 2006 more than 5,000 of them had the disease; by 2015, the total number of cases had reached 20,000.

Salivary glands, stomachs, and breasts also absorb I-131 and may get cancerous. Women who were lactating or pubescent during the accident were particularly at risk for breast cancer, which by 2006 had approximately doubled in heavily contaminated areas.

Our next foray looks at cancer in workers in nuclear power plants, and in adult living near them. Then we will focus on their children, because they are most at risk. – Rappler.com

Born in Manila and educated at UP Diliman and the University of Southern California, Dr. Kelvin Rodolfo taught geology and environmental science at the University of Illinois at Chicago since 1966. He specialized in Philippine natural hazards since the 1980s.

Keep posted on Rappler for the next installment of Rodolfo’s series.

Previous pieces from Tilting at the Monster of Morong:

- [OPINION] Tilting at the Monster of Morong

- [OPINION] Mount Natib and her sisters

- [OPINION] Sear, kill, obliterate: On pyroclastic flows and surges

- [OPINION] Beneath the waters of Subic Bay an old pyroclastic-flow deposit, and many faults

- [OPINION] Propaganda about faulting, earthquakes, and the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Discovering the Lubao Fault

- [OPINION] The Lubao Fault at BNPP, and the volcanic threats there

- [OPINION] How Natib volcano and her 2 sisters came to be

- [OPINION] More BNPP threats: A Manila Trench megathrust earthquake and its tsunamis

- [OPINION] Shoddy, shoddy, shoddy: How they built the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant

- [OPINION] Where, oh where, would BNPP’s fuel come from?

- [OPINION] ‘Megatons to Megawatts’: Prices and true costs of nuclear energy

- [OPINION] Uranium enrichment for energy leads to enrichment for weapons

- [OPINION] Introducing the nuclear fuel cycle

- [OPINION] On uranium mining and milling

- [OPINION] Enriching and fabricating BNPP’s uranium fuel

- [OPINION] Decommissioning BNPP, and storing the nuclear dragon’s radioactive manure

- [OPINION] So how much greenhouse gas does nuclear power really generate?

- [OPINION] Getting up close and personal with the atom, and its nucleus that powers NPPs

- [OPINION] The nucleus and isotopes: Why BNPP needs Uranium 235, Not Uranium 238

- [OPINION] What you should know about radioactivity

- [OPINION] Uranium mine waste and the weird idea of half-life

- [OPINION] How nuclear power plants work: Hot monster piss from Morong

- [OPINION] What if there was a spent-fuel pool accident at the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant?

- [OPINION] Nuclear weaponry, its radiation, and human health

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] Who decides whether Bataan should go nuclear?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/08/imho-bataan-nuclear-powerplant.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=271px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Nuclear energy should not become major part of Philippine energy system](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/01/nuclear-energy-january-26-2023.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=205px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.