SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The West Philippine Sea is about a third of the 2.2 million square kilometers of the Philippines’ maritime domain (territorial waters, Exclusive Economic Zone, and Extended Continental Shelf). It’s about 20% of the South China Sea’s area of 3.8 million square kilometers. It’s a rich fishing ground, has considerable hydrocarbon deposits, and is part of the South China Sea (SCS) where ships transit commerce and trade between Asia and the world.

There are contending territorial claims to parts of the SCS and challenges to the internationally recognized jurisdiction of the Philippines over the WPS. They’re creating grave economic and political security concerns in the world. To establish presence, some claimants and challengers are converting reefs and atolls into lands for habitation. They have created a regime of resource extraction that encourages illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. These have decimated and depleted large areas of water once thriving with life. In these places, the once living sea is gone.

As a certain genius mind was supposed to have once said (albeit not in these exact same words), “We can’t solve our problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them,” it is clear that we need a new way of approaching the WPS issue. We should start by seeing the WPS as a totality, beyond the monolithic marine resources that everyone tends to see. There are its natural processes, products, and outcomes of complex ecosystem dynamics that create diverse life forms and conditions for life. They define the unique features of the environment in the WPS. They affect the state and life systems in surrounding seas and lands. They produce ecological, economic, and social benefits (and risks) to people, which give the WPS immense value.

Ecological Value. The WPS hosts marine biota, materials, and spaces that people use. It produces fisheries and other organisms that are consumed for food. It has materials and other natural assets that could be used to support lifestyles and cultural practices of people living around it. Its marine life is among the most diverse in the world. It hosts a rich treasury of genetic information that sustains life. Its hydrocarbon reserves are a life spark to a chronically energy-anemic country. Its vast area offers spaces for commerce and industries. These are provisioning ecosystem services of the WPS.

The WPS also supports life systems. Its ecological processes sustain life within the WPS, in the SCS, and in waters and lands beyond it. Its coral reefs, seagrass meadows, mangroves, sandy bottoms, and intertidal flats support carbon, nutrient, and other biogeochemical cycles that maintain the populations of biota in nearby waters and lands. Winds and currents in the WPS, for the most part due to heat exchanges between the sea and the atmosphere, the moon’s gravitational pull, and the Coriolis force of earth’s rotation, create upwellings and downwellings that stir up life across its depths and surfaces.

Another ecosystems service of the WPS is its ability to regulate the natural processes that allow life to thrive. It serves as a conduit of surface heat flows across the SCS and the northeastern Pacific and the Sulu Sea. These heat flows affect the biological productivity and biodiversity of these waters and surrounding lands. They regulate weather conditions. The WPS absorbs atmospheric carbon that helps regulate the climate. Its plankton and microplankton populations produce oxygen that sustains life. Its waters absorb and disperse plastics and chemicals which affect the condition of its biota. It spreads larvae, nutrients, and organisms that affect life systems in nearby lands and seas.

The ecosystem services of the WPS make it an important influence on peoples and cultures. This is its cultural service. Its ecological processes affect ways of life, seasonal behavior patterns, diets, and livelihoods in surrounding communities. They shape opportunities for social and cultural expressions, including among Indigenous peoples whose lifestyles largely revolve around nature’s primary productivity. They create amenities for human pleasures and emotional experiences. Natural formations and phenomena in the WPS like beaches, rocky outcrops, surfs, sunsets, and moon rises mirrored in the sea, create occasions for recreation, rituals, and moments for introspections and celebrations. These elevate the human spirit.

Economic Value. Ecosystem services generate economic value. This value could be gleaned from indications and estimates of the worth in money terms of some of its ecological production and processes:

Fisheries. In 2018, 27% of catch fisheries in the Philippines were harvested from the WPS. They were worth P40.687 billion. They fortified the nation’s food security and protein supply and the health and nutrition of Filipinos. Fisheries provide 36% of the Filipinos’ protein intake. They contain micronutrients that improve brain and cardiac health, growth and body development, and joint support. They help prevent immunity disorders, reduce inflammations, and control weight.

Marine biodiversity. Seaweeds, seagrass meadows, mangroves, and coral reefs are known to have high economic values. While there are no estimates of their value in the WPS, seaweeds were valued at $10 billion/year globally in 2013. In 2018, the Philippines produced P11 billion worth of seaweeds. Worldwide, seagrass beds were worth $8.3 trillion in 2004. Intact mangroves were valued from $500 to $1,500/hectare/year in 2000. Coral reefs were valued at $352,248/hectare/year globally in 2007.

Marine biodiversity in the WPS offers potentials for biotechnology applications in agriculture, medicine, energy, and environmental remediation. Marine cones, sponges, and seaweeds could be sources of peptides and compounds for biotechnology uses. The global biotechnology industry is estimated to grow to $2.44 trillion by 2028. If properly and safely used, the genetic treasury of the WPS could shift the locus of its economic value from the consumption of organisms (that’s difficult to sustain) to only the use of their genetic information (which imposes little threat to stocks).

Hydrocarbon. In 2018, the WPS was reported to hold an estimated 125 billion barrels of oil and 500 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. These included proven and suspected reserves. Earlier in 2012, the known reserves were estimated to meet the country’s energy needs for two decades. That time, Malampaya was generating $1 billion/year of gas and was saving the country of $500 million/year in foreign exchange for importing fuel. Malampaya spawned the Philippines’ natural gas industry.

Commerce and Industry. The value of trade transiting the SCS is about $3.4 to $5.3 trillion a year. That’s 21% of global trade in 2016. They include oil, gas, and raw and processed materials that are crucial to the economies in East and Southeast Asia. They transit the SCS Sea Lines of Communication (SLOC). Portions of this SLOC run through the WPS. Transited trade include most of the exports and imports of the Philippines valued in December 2021 at $17.75 billion.

The WPS hosts four big industries: fisheries, hydrocarbon fuel production, port operations, and tourism. Two of the Philippines’ 12 Fisheries Management Areas (FMAs) are in the WPS. They’re the second and third largest in the country. Petroleum and gas production continue in the WPS and new ones are being eyed in the Recto Bank. The biggest seaports in the Philippines face the WPS (Manila, Batangas, Subic, San Fernando in La Union, Limay, and Zamboanga).

Many tourist destinations in the country are in the WPS (or are in its contiguous waters). These include El Nido, Taytay, and Calamian Islands in Palawan; Boracay in Panay; Puerto Galera in Mindoro; and destinations in western Luzon (like in the Ilocos region, Subic Bay, Pangasinan, La Union, and Batanes).

Estimates of the economic value of fisheries and hydrocarbon production have been noted earlier. There are no clear numbers on the value of port operations but these could be implied by the value of Philippine trade, most of which are shipped by sea. Tourism is a big industry for the WPS. It generated $9.39 billion in revenues in 2019. It accounted for 5.4% of GDP in 2020. It averaged 7.4% of GDP from 2000 to 2018.

Value to society. The combined ecological and economic values of the WPS give it its value to Filipino society and others living in waters and lands around it. They create prospects for pursuing preferred lifestyles, traditions, languages, norms, and world views. Goods and services from the WPS are among the tangible and intangible cultural heritage of communities around it: their sacred groves, legacy foods, traditional technologies, housewares and products, and local art forms (music, visual arts, dance, architecture, and materials used to create or articulate them). Local lifestyles and cultures are reflected in the infrastructure and content of marine tourism in the WPS.

Human security is one immeasurable value of the WPS to society. Beyond food security, protein security, and physical security, human security ensues from people being able to safely and peacefully avail of the benefits from the WPS. Peace and security are critical conditions for people to sustain life and lifestyles, particularly those with fragile populations and cultural infrastructure like Indigenous peoples, and any others affected by the biogeographical and climatic dynamics of the WPS.

A legacy of the West Philippine Sea

These valus of the WPS help shape the identities and ways of life of Filipinos and of others around the SCS and beyond. They’re irreplaceable and inimitable legacies – a common heritage – to them. These have to be protected and preserved, secured and sustained, because if they’re lost they’d erode, even break, cultures and life systems around it and beyond.

Jurisdiction embeds both obligation and right to take care of the compass of its authority. This way, the Philippines has the ascendant legal, political, and moral position to take the lead in assuming custodial responsibility over the ecosystem services of the WPS, and do so for Filipinos and for all others who benefit from them.

A narrative of inclusionary protection could be pursued as policy by the Philippines despite and alongside the narrative of exclusionary claims being posed by challengers to its jurisdiction over the WPS. Collective protection of the heritage value of the WPS could be made a fulcrum for constructive engagement among stakeholders of the WPS and the SCS, even if the challengers opt to maintain and not void their challenge. Amidst conflict, “a cooperative approach aligns with the process of interest-based or integrative bargaining, which leads parties to seek win-win solutions” (Spangler, 2003). Challengers might agree to recast the WPS discourse from territorial contentions to collaborations on a common purpose of protecting its universal heritage value. This, because losing this value would emasculate any and all interests and stakes on the WPS.

Difficult? Unrealistic?

Cooperation amidst maritime conflicts has been done in Antarctica, in the Caribbean, the North Atlantic, between Maine and Nova Scotia, in the Natuna Sea between Indonesia and Malaysia, and the Great Lakes between the US and Canada. It’s not impossible. It’s the better option than the volatile situation we have now. It’s the right and responsible option. In fact, it’s the only option we have to protect the heritage value of the WPS that is of great worth to all in the Philippines, Asia, and the world.

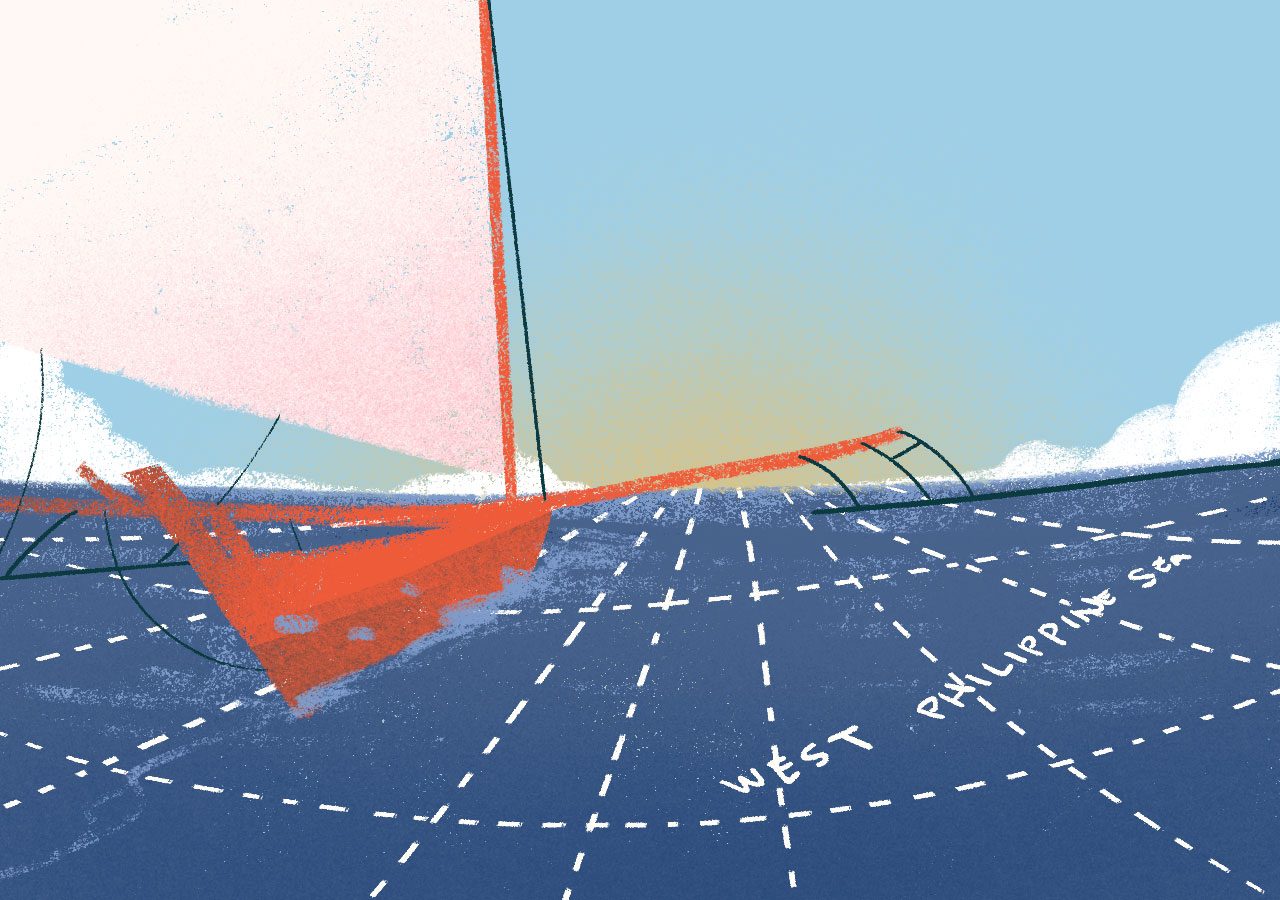

Sailing towards a common ground may indeed be difficult in this case, but the times call for a new mindset. If the ecosystem services that create the heritage value of the West Philippine Sea were not protected and secured, interests on any part of it would not make sense. The Philippines and those who challenge its jurisdiction over it, must recognize and commit to the elemental need to protect the universal commons in the West Philippine Sea. – Rappler.com

Ben S. Malayang III is Silliman University Professor Emeritus and USAID Fish Right Program Research Fellow for West Philippine Sea

This article is based on the synthesis paper “The Heritage Value of the West Philippine Sea” (2022) that was prepared for the USAID Fish Right Program by Ben S. Malayang III, Lourdes Cruz, Joan Regina Castro, Rodelio Subade, and Ramon Benedicto Alampay.

The views expressed and opinions contained in this article are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the Fish Right Program.

About USAID Fish Right Program

The USAID Fish Right Program is a partnership between the governments of the United States and the Philippines to promote fisheries management and marine biodiversity conservation. Fish Right enables sustainable fisheries by reducing threats to biodiversity and improving marine ecosystem governance.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[DOCUMENTARY] Our 15 kilometers: Small fishers fear losing municipal waters to big operators](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/our-15-kilometers-iuu-fishing-docu.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=279px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

This is a brilliant, thoughtful analysis — and one that points to a bright Philippine future, if the political will can be summoned to protect this country’s sovereign maritime natural treasure.