SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[Vantage Point] Robust dollar pummels emerging markets](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/09/robust-dollars-pummeling-markets-September-10-2022.jpg)

Former agriculture secretary Manny Piñol came under fire from netizens about his take on the downward trajectory of the Philippine peso against the US dollar. According to him, “P57 to $1 is not entirely bad. It’s good for our OFWs (overseas Filipino workers) and local food producers. This crisis could open opportunities.” On Tuesday, September 6, the peso crashed to a new all-time low of P57 to a dollar as the greenback strengthened on the sustained interest rate hikes enacted by the US Federal Reserve. The dollar, which has been steeply rising for about a year, has now rivaled the euro’s value for the first time in two decades.

While Piñol’s statement seems insensitive coming at a time when many Filipinos could hardly make ends meet, his pronouncement by and large holds some truth. It’s the nature of the free market regime. There’ll be no winners if there wouldn’t be any losers. It happens every trading day at the Philippine equities market. There are gainers and there are losers. What makes it bad is if losers outnumber those who get the chips.

In a capitalist system, money goes where money grows. With all the global turbulence, ordinary and institutional investors will seek investment haven in any tradeable instruments they can get their hands on.

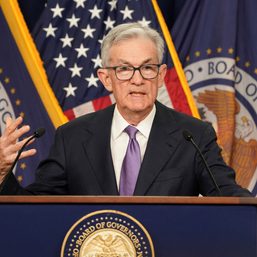

While the US economy is still finding its right balance, a combination of events has made the American currency a top choice for investors. The dollar has been soaring mainly because the Federal Reserve is not letting up on hiking interest rates faster than other major countries. Investing in the US dollar now is just like parking your money in an impenetrable vault. As prospects for the global economy dim, jittery investors gobble up dollars, particularly US Treasury bonds, thus catapulting the US currency to new highs. The rising dollar is not about the health of the US economy. It is about how much investors fear a global economic meltdown.

Here is what I think Piñol is right about:

Year-to-date, all major asset classes all over the world, with only one exception – the US dollar – have fallen:

One of the world’s largest currency hedge funds, P/E Investments from Singapore, generated an outstanding 18% year-to-date, by riding reliable statistical patterns across markets.

In the short-to-medium term (< 5 years), macroeconomic factors in the US and other emerging markets often dominate what happens to Philippine asset prices. When risk appetite is low, countries with trade and budget deficits are particularly vulnerable (spending more than they make) as they are seen as riskier countries to invest in. However, Philippine exporters will benefit from a weak currency and offer a currency hedge in the extreme case of a complete currency collapse.

Macroeconomic factors can also create unique opportunities for certain industries and types of companies. A weak currency will make the country a destination of choice for foreign tourists. Aside from benefiting the tourism industry, foreign currencies will also flow into other industries and the broader economy. A devalued peso also benefits OFW families. If you’re an investor and are taking a longer-term view (> 5 years), you can look at market and currency weaknesses as opportunities rather than risks.

But here is why Piñol’s argument falls short:

Experts fear that emerging markets, including the Philippines, could experience capital flight, inflation, or even debt defaults as the dollar’s two-decade dominance empties the taps. A strong dollar severely impacts emerging economies. A low US interest rate makes it palatable for investors to flock to emerging markets (nations that are in transition to become developed economies). But when US rates start to climb and the US dollar strengthens, foreign money starts exiting from these countries.

Recall that past emerging market crises were partly caused by the dollar strength. The dollar’s continued climb forces economic managers of developing countries to constrict monetary policy to prevent their own currencies from crashing. Failing to do so would aggravate inflation and make servicing dollar-denominated debt more expensive.

Piñol argues that OFW families could buy more goods and services from an expanded dollar value in peso terms. But a stronger dollar still means higher imported inflation, especially with 30% to 40% increases in food and oil prices (Source: World Bank). High commodity prices in the market practically wipes out whatever theoretical gains these OFW families will have from higher foreign exchange rates. Filipinos are most affected by high commodity prices and a further uptick in the prices of oil and food spells more casualties. Experts also fear that shortages of almost all commodity items, such as sugar, rice, salt, pork, and chicken, among others, could further strain Filipinos’ emptying purses.

Government records show that the most important categories in our Consumer Price Index are: food and non-alcoholic beverages (39% of total weight); housing, water, electricity, gas, and other fuels (22%); and transport (8%). The index also includes health (3%), education (3%), clothing and footwear (3%), communication (2%), and recreation and culture (2%). Alcoholic beverages, tobacco, furnishing, household equipment, restaurants, and other goods and services account for the remaining 15%.

Will exporters benefit from a devalued peso? Yes, because they now get P56.80 (forex rate as of this writing) for every dollar they make, compared with P55 to a dollar only a few months back. Conversely, importers now pay more pesos for the dollar cost of imported goods. Since we import more than we export, the whole country loses.

According to World Bank records, the country’s trade deficit sharply widened to $5.93 billion in July 2022 from $3.50 billion in the same month a year earlier, mainly due to a surge in imports. Amid robust domestic demand as the COVID-19 situation improved further as well as surging commodity prices, inbound shipments jumped 21.5% year-on-year to $12.14 billion, even as exports fell 4.2% to $6.21 billion. During the first seven months of the year, the trade gap jumped to $35.74 billion from $21.46 billion in the same period in 2021. All these show that dollar strength translates to higher import bills which in turn accelerates inflation.

Remember how the combination of higher debt costs, economic mishandling, and political unrest pushed Sri Lanka into full-scale crisis? Experts are warning that this scenario can happen to any emerging market.

A strong dollar also means that we have to pay more pesos to service our foreign obligations. The country faces P12.89 trillion debt as of end-July 2022. Of this total, 31.5% represents foreign debts, and 68.5% for domestic borrowings. On July 31, our peso-dollar foreign exchange rate was only P55.3463 to $1. You do the math.

Many poor countries are unable to borrow in their own currency in the amount or the maturities they wish because lenders are allergic to assume the risk of being paid back in these borrowers’ unstable currencies. Thus, poor countries more often scrounge for funds in dollars, guaranteeing to pay back their obligations in greenback, immaterial of the prevailing exchange rate. Thus, as the value of the dollar rises compared with other currencies, settling their debts turns out to be more expensive in terms of domestic currency. In public debt lingo, this is what is call the “original sin.”

Finance Secretary Benjamin Diokno, however, is confident that the Philippines will be able to pay all its debts in due time. The debt-to-GDP ratio, he said, will ease to 61.8% by the end of the year, dropping gradually through the years until it descends below 60% by 2025. It is seen to further drop to 52.5% by the end of the Marcos Jr. administration in 2028.

Will the dollar continue to climb in the near term? Chess grandmaster Kenneth Saul Rogoff, an American economist, Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy, and Professor of Economics at Harvard University, offered this scenario as quoted by Vox Media, an American news and opinion website: The dollar could fall if the war in Ukraine were to “miraculously” end, easing pressure on European economies and boosting their currencies.

He said that the dollar could also fall if the US goes into recession and the Fed has to cut interest rates to stimulate the economy. Rogoff believes an economic downturn in the US could make investing in US assets and companies look less attractive, resulting in a devalued dollar.

With this “very uncertain environment,” Rogoff pointed out, “the exchange rate probably is going to be hard to predict.” It certainly looks like a bumpy ride ahead for the Philippine peso. – Rappler.com

Val A. Villanueva is a veteran business journalist. He was a former business editor of the Philippine Star and the Gokongwei-owned Manila Times. For comments, suggestions email him at mvala.v@gmail.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.