SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – What do you remember most about Martial Law?

As the Philippines commemorates 51 years since the declaration of Martial Law, revisiting this dark period in our history can be challenging – especially as we live under another Marcos presidency.

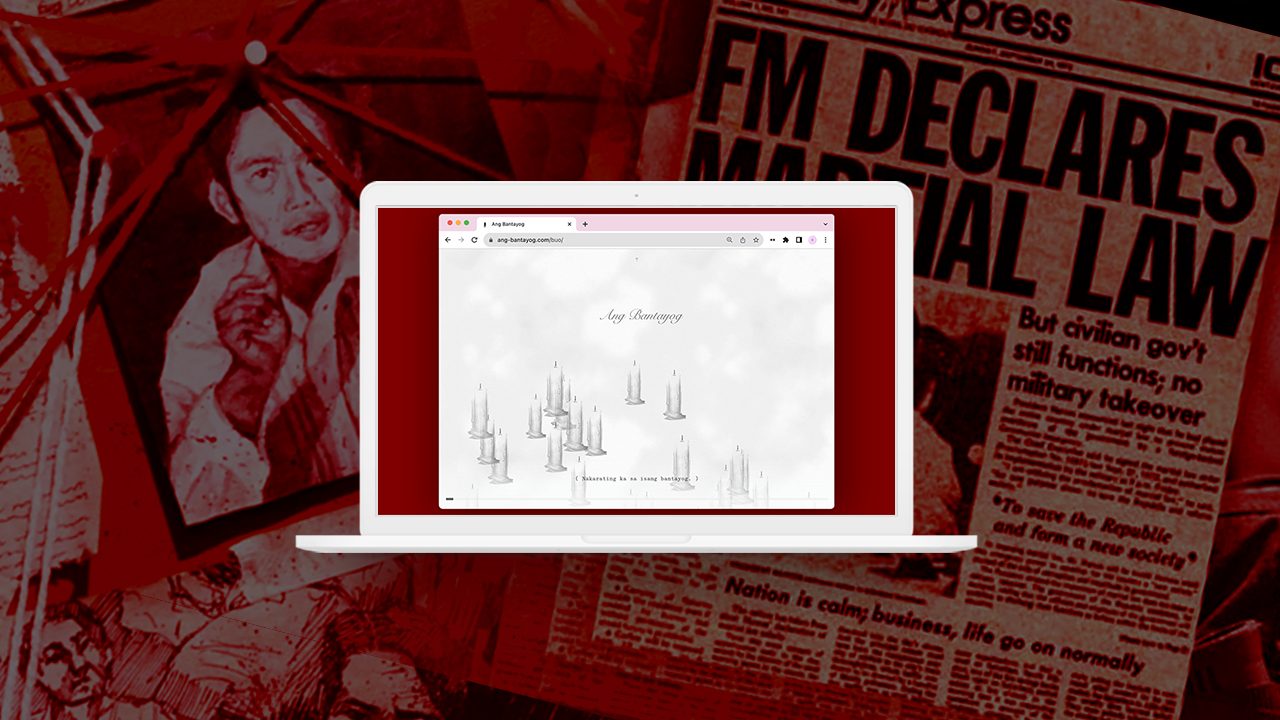

San Francisco-based web designer and internet artist Chia Amisola hopes to raise the question on how people can gather together and remember the atrocities during this period through their website art piece “Ang Bantayog.”

Amisola launched the “digital monument” on September 21, the same date in 1972 when former president Ferdinand E. Marcos signed Proclamation 1081, placing the entire Philippines under martial law.

The website’s layout consists of 11,103 candles, representing the number of state-recognized victims of human rights violations during the Martial Law period across the Philippines.

Those who visit the website can light a candle once a day to reveal the name of a Martial Law victim.

“I scraped and drew from this list as it was important for me to highlight names on the website, akin to how names are etched on physical memorials, all while recognizing that it is inexhaustive,” Amisola told Rappler.

Shared memory

Amisola started conceptualizing the “Ang Bantayog” website in April 2023 due to “[their] growing interest in digital preservation and memory” and as a response to the election and administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

Their initial concept involved a website with candles flooding the page in “a seemingly infinite vertical scroll,” taking inspiration from stone markers to street memorials for Martial Law victims.

During the development period of the website, the web designer reached out to Bantayog ng mga Bayani executive director May Rodriguez in May to share their concept with the group. They later made further tweaks to the site on September 19 before launching the site on the internet.

The tweaks included the placement of two modes on how the victims’ memories are shared on the site: “Isa (one)” and “Buo (whole).”

In the “Buo” version, memories can be shared where users can see all the candles lit by those who visited the site. If a candle is lit, users can also hear a match strike sound on the site.

Meanwhile, the “Isa” version can retain data of individually lit candles on the site through the web browser’s localStorage for future visits. However, the memory will be erased if website data is erased from the browser.

Amisola says that the design of both versions is intended as a metaphor where “the limitations of machines [are] not too different from those of man” that replicates the struggle for people to go beyond “a passive recognition of [atrocities]” committed during Martial Law.

“I am most interested in commemoration as catalysts and interventions. And so this is an exercise of collective memory more than the impossible act of replicating memory itself,” they added.

The web designer also recognizes that sites such as “Ang Bantayog” are not meant to be taken equally to a commemorating of Martial Law through a monument.

“A website positing itself as a memorial might be doomed. Dwelling on the web itself means continuously losing access to one’s own past. I’m creating something that by nature is designed for its own disappearance, as a memorial to those who have disappeared,” Amisola said.

Connecting to the motherland

Beyond recording the lives of those who were affected by one of the darkest periods in Philippine history, Amisola also took on the project to further connect to the Philippines and their relationship with technology.

Amisola graduated with a degree in Computing and the Arts from Yale University in 2022 and currently works as a product designer for Figma.

“As I’ve been physically distanced from the Philippines since coming to the US for college, I have been interested in treating websites as space, literally as sites, as a form of gathering and social practice,” they said.

“Ang Batayog” is not Amisola’s first project that places an emphasis on making Philippine history accessible online. They also spearhead the Philippine Internet Archive, which aims to preserve and archive digital work and movements that surround communities that have “historically been written out of the internet.”

“I’m working on it as a history of Filipino networking that decenters the internet’s militant [and] colonialist roots and instead looks equally at those who make its access possible: Pisowifi vendors, infrastructural maintainers, tech laborers, call center workers, and alternative media publications,” Amisola said.

Amisola hopes to use “Ang Bantayog” and the Philippine Internet Archive as a way to combat disinformation and historical distortion, something that benefitted President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. in the 2022 elections.

“Local narratives and community histories, such as that of many Martial Law survivors, often go underdocumented on the internet, or if they are, might be suppressed and lack the avenues for apt distribution,” they added.

Technology as a tool

Amisola shares from their experience in archiving Philippine history online that records can be a “tool for both oppression and liberation” as structures that form our understanding of past events.

“Memory is a collective and lifelong practice to remember beyond physical, or digital, monuments; to provide individuals the tools and funding necessary to understand and deconstruct the past; and to recognize that no one institution has authority over narrative. Ultimately, it is in how each of us remember,” they said.

This comes especially as the Department of Education plans to change “Diktadurang Marcos” to “Diktadura” in the grade 6 Araling Panlipunan curriculum of the new Matatag curriculum, a move that critics say will “distort history” on the legacy of the late dictator.

The “Ang Bantayog” creator also recognized that they understand that the magnitude of those who were traumatized and murdered from Martial Law atrocities goes beyond the 11,103 victims that inspired their site.

According to a report from Amnesty International, about 70,000 people were arrested, 34,000 tortured, and 3,240 killed from 1972 to 1981.

“Even if these names represent just a fraction of an incalculable loss, I was struck by how few have [a] record of [their] life online, beyond their name on the roll on this one government website’s table,” Amisola added.

They hope that other records would be found and archived that would recognize the courage, sacrifice, and identity of Martial Law victims that goes beyond a name listed on a government document.

Amisola also believes that people should look into technology as a tool to help people be discerning of their own time and attention, instead of focusing on optimization and algorithms that “offload the work of scrutiny, discovery, and discernment to oft corporate interests that do not work in our favor.”

“The internet was the source of my political awakening, as with many of my peers and mentors…. I view the internet most as a tool and medium, thinking about it in its simplest roots for networking,” they said.

Since the launch of “Ang Bantayog,” Amisola would keep a tab of the “whole” version at all times to see and hear if a new candle is being lit.

“I am glad to feel interdependent in the work of memory, and of recognition of our environments that work to repress it.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] In the Philippines, the fight for the climate is a fight against state violence](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/imho-contexualizing-state-violence.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=265px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] A fighting presence](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-a-fighting-presence.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=441px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Closer Look] ‘Join Marcos, avert Duterte’ and the danger of expediency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-trillanes-duterte-expediency-june-29-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.