SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

“Kapag ako p’wedeng bumoto, iboboto ko si Marcos. (If I could vote, I would vote for Marcos.)”

It was a conviction spilled on the dinner table, and Susan Macabuag had to clean it up.

Macabuag was an activist during the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos. She was a student of the University of the Philippines (UP) who dropped out to do organizing work, leaving the student commune as soldiers closed in. A year after Marcos declared Martial Law, in a Bulacan town she no longer remembered, Macabuag gave birth to her son.

After Marcos was deposed, she pivoted to being a mother and then became a government employee in the province of Antique. She later returned to Manila with her husband. In 2022, quick-witted at 71, Susan headed the museum of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani, the institution whose mission was to protect the memory of the People Power Revolution and its martyrs.

Her battle for memory over dinner involved her grandnephew, a wannabe voter for Marcos Jr.

Susan asked the child, no older than 10, “How come you knew about Marcos?”

“Tiktok.”

It was a new era. Some 36 years have passed since the dictator and his family were exiled – a period that spanned a generation. The family has flown back to the country and consolidated power. Crowning their return is, to date, the strong possibility of returning to the presidential palace.

Those who have witnessed the brutality and corruption under Marcos were suffering a relapse, reeling over a nation that seemed to be casting away a memory they once thought was inextricable.

Among those rolling in their beds were the women of the Bantayog ng mga Bayani. We spoke with four of them.

They found themselves impotent – undermanned, underfunded, untrained, and caught by surprise by a war set in a landscape of memes and viral videos, where truth was what one made of it as long as it was shared and liked enough times.

The women did not intend to give up more ground.

“In terms of truth and the proofs of our history, they are here, we are very strong in that. But in terms of these new ways to spread information, we are not that ready,” Macabuag told Rappler in an interview on February 22, a few days before the 36th anniversary of the People Power Revolution that toppled Marcos.

What calamity does to memory

Two years since the pandemic forced museums to shutter, the Philippines finally lifted its lockdowns. While other galleries have started to reopen, the Bantayog remained closed.

Its famous monuments, the Castrillo-sculpted Inang Bayan and the gold paint-engraved Wall of Remembrance, could easily be sighted as they were all outdoors. The problem was the museum, the library, and the Bantayog’s office, contained in a decaying two-story building.

In November 2020, when Typhoon Ulysses submerged Manila, a section of the building’s roof – the one covering the building’s prized Hall of Remembrance – collapsed, leaving the hall off-limits ever since. To prevent the danger of fire and electrocution, the nearby wirings were disabled and then left to hang naked.

A hole gaped in the ceiling of their ground floor conference room, another victim of rainwater and decay.

Inside the library, the shelves were half empty, its books evacuated after termites were discovered in its gaps.

The museum was no larger than a two-bedroom apartment, apt only for 30 people at a time before the pandemic, while the library was half the size of a classroom, its space enough only for 10 visitors and fewer than 2,000 books at a time. The library had no air conditioner. The museum had four. None of them worked.

Cramped and poorly ventilated, the building, along with all the books and records it kept, remained closed to the public.

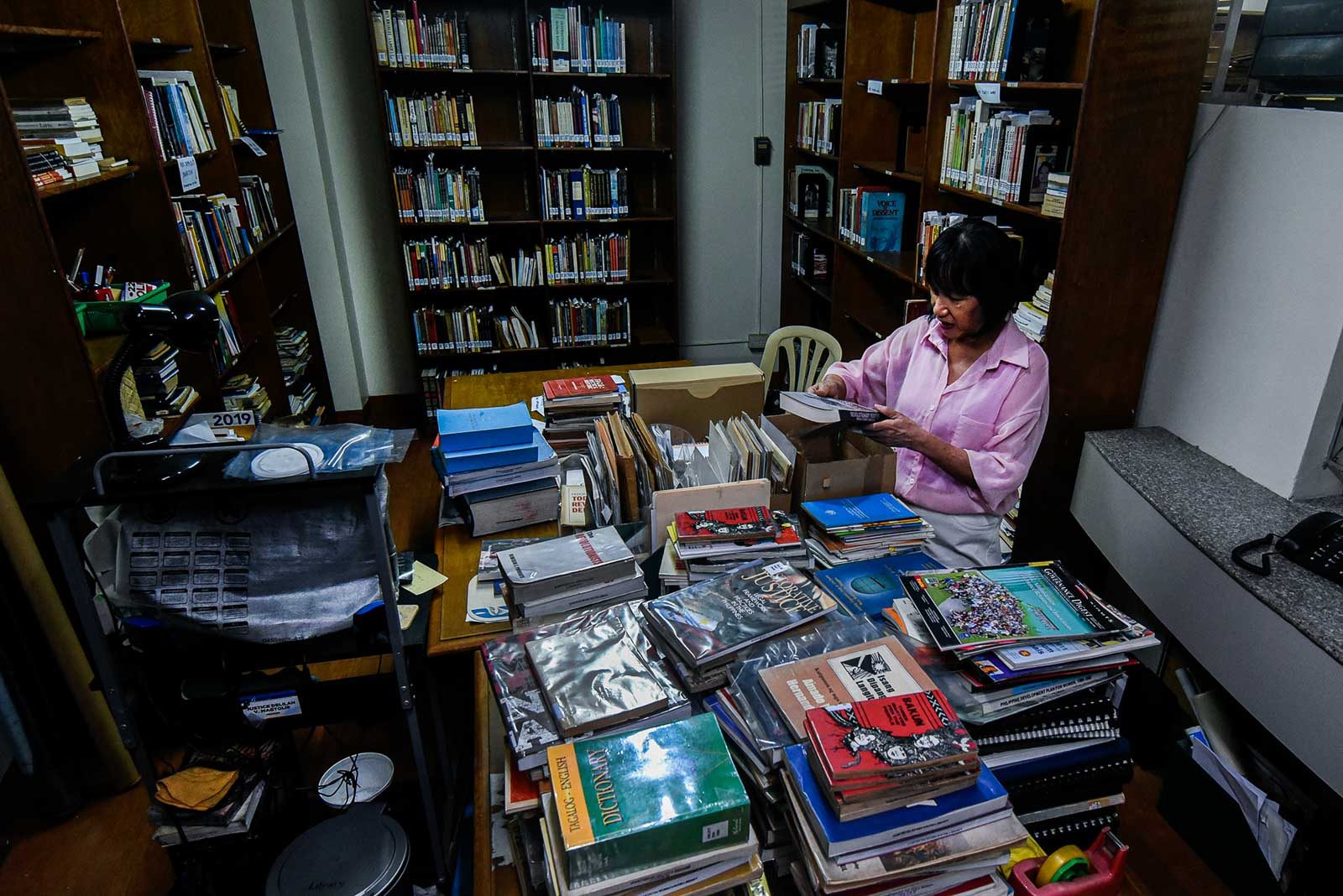

The woman with the books

Sarah Ferdinez was alone at the library. It was February 21, and the Bantayog had just received a special delivery, the care of which was entrusted to Sarah.

The library’s only table carried heaps of books that were salvaged from the pests, and a black typewriter half Ferdinez’s size. She lifted it and placed it at the back of the table then pulled out an SM Supermarket plastic bag and dropped it on the table with a thud. It was the delivery. Inside were the browning newspapers from the Marcos era.

The titles told history:

“FM crony tells all”

“The ‘secrets’ of Malacañang unraveled”

“Palace bans fotog”

“Imelda’s past revisited”

“Awesome people power”

“Marcos flees”

“Cory forms Cabinet; No raps vs Marcos”

Ferdinez was to scan each clipping for their archives. I asked where the scanner was. She pointed to her phone. The library’s real scanner was in the room next door, she said, broken.

“Walang budget (We don’t have a budget),” Ferdinez said, letting out a self-consoling chuckle.

At the climax of the Edsa protests, Ferdinez was an organizer of fisherfolk. She remembered being in front of Camp Crame in Quezon City, taking pictures. She saw people lie down on the ground to stop the tanks from advancing.

“Nagpapasagasa talaga sila, kasi nagpoprotesta sila eh (They allowed themselves to be run over. They were protesting, after all),” she said.

In 2022, Ferdinez was an assistant in the Bantayog Library, by herself as the other assistant was ill.

She did not study how to manage a library, with all its indexing and assigning of accession numbers that confused her, but twice a week she showed up, caring for each book, saving them from the termites.

We looked at the newspaper clippings together, smirking over one headline that read, “Power no longer interests me – FM,” and another that said, “I know how it is to be poor – Imelda.”

“Talagang nakalimutan na nga (It has truly been forgotten),” she said.

Boy’s girl

When you walk to the leftmost corner of the Wall of Remembrance and look at the name at the top, you will see “Inocencio ‘Boy’ Ipong.”

Ipong was a calm yet humorous activist in Mindanao. He played the flute and broke bread with nuns, who organized farmers and Lumad communities after Marcos allowed the military to let loose. For 10 days in 1982, Ipong disappeared, only to be found with bruises all over his body inside a police station, tortured as they forced him to claim a name that was not his own. In 1983, as he sailed for Cebu, he faced a storm at sea. Survivors recounted that as the waves swallowed their ship, Ipong was last seen with nuns huddled in prayer.

Forty years later, in the shadow of the wall where his name was etched, stood his daughter Karla – a collected woman who looked too young to be 40. She was a researcher at the Bantayog.

Karla knew only of the broad strokes of her father’s past until, in 2013, Ipong was honored by the foundation. The next year, Karla’s family needed to produce her father’s death certificate. He did not have one. He used an alias when he boarded the doomed ship, cautious of the military tracking him through the registry. He doubted he could survive another disappearance.

Karla went to the Bantayog and gathered clippings to prove her father was dead. The same year, Karla decided to dedicate her life to preserving the memory of other Martial Law martyrs.

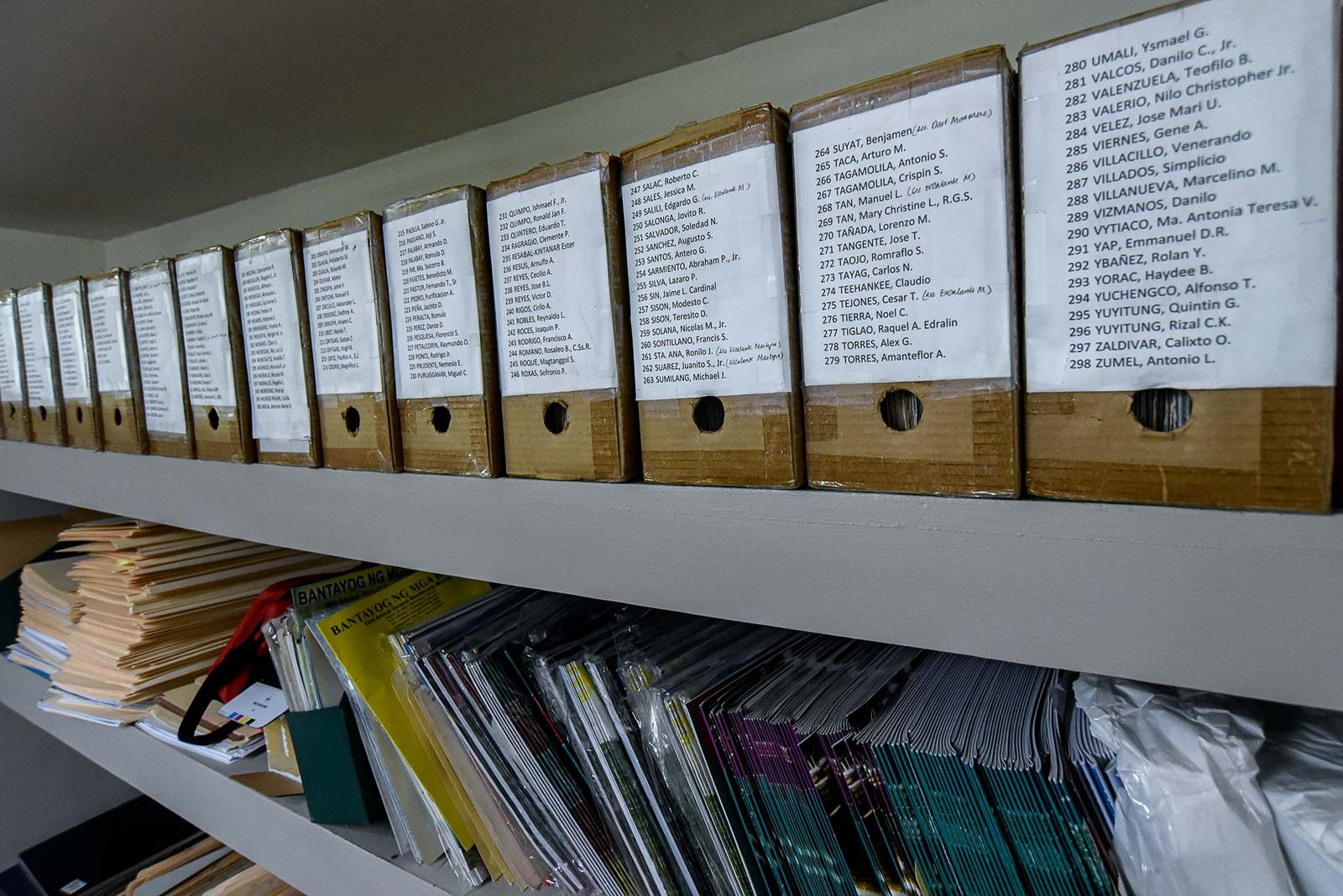

Karla kept the names of nominees for inclusion in the Wall of Remembrance, scouring for traces of heroism. She flew to their hometowns and spoke with their families, colleagues, and communities.

She had a backlog of over 200 names – a quantity that she found impossible to complete. Each name took as long as 10 years to be approved for carving, and Karla did it all alone. She used to work with two others, but they grew too old for flying to the provinces with her, speaking with people without the guarantee of finding what they were hoping for.

There were families who opted to reject their kin’s inclusion in the monument, afraid that the military would strike them down if they spoke of the atrocities. There were families who refused to talk, not finding a reason why they should share with a stranger a memory they would rather bury. There were families whose members had died, taking their memory with them.

As Karla saw it, the world of those who remembered was slowly getting smaller and smaller.

In 2015, Karla was at the Bantayog as it carved more names onto the Wall. There, she met a son of a Martial Law martyr. They added each other on Facebook. In 2016, as Karla scrolled through her feed, she saw him post a photo of Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

“He voted for Bongbong Marcos.”

The women and their hope

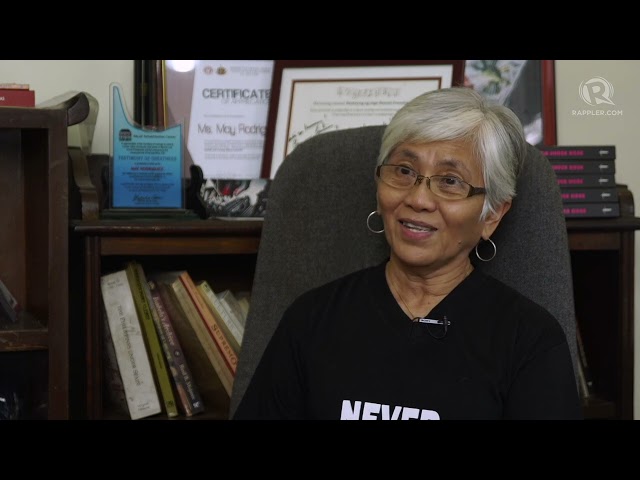

The leader of Bantayog was the woman with silver hair, May Rodriguez. Rappler spoke with her in her office on the sweltering day of February 23. She opened her window, gestured for me to rest, and she sat behind her desk. Rows of books lined her wall, telling stories of the dictatorship and the revolution.

“Everything was forbidden,” Rodriguez recalled.

Rodriguez was a third-year student at UP when Martial Law was declared. She went underground and wrote for the revolutionary press. She distributed the banned papers herself, secretly passing them over as she boarded jeepneys and paid tribute in the church.

She saw Marcos distort history as he made it. The crony-owned papers only showed the beautiful: infrastructures that promised abundance, streets that were empty and peaceful, Marcos preaching about his New Society, Imelda. It was propaganda to hide the debts, the deaths, and the corruption. She had to let the world know.

On the first year of military rule, soldiers captured Rodriguez. They tortured her, saying she was “spreading subversive materials.” She was arrested once again when protests reached their height in 1983. Marcos himself signed for her release, she bragged.

“His skin was so dark. I knew he was sick as soon as then,” she said.

After Marcos was deposed, Rodriguez reported for a news agency then joined Bantayog as a researcher. In 2015, she became its executive director, just a year before Duterte had the corpse of the dictator Marcos buried at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

“We knew the memory would fade. We know there were efforts for the Marcoses to return. We did not expect this vigor, this huge push they are doing just to accomplish it,” she said.

In their battle to preserve memory, Rodriguez did not moan about her colleagues being few: only eight worked full-time while seven volunteered. Neither did she whine about how strapped for cash they were. She faced worse under the Marcos rule. When an organization lacked people and money, there was only one thing to do.

“We’ll have to force ourselves to rethink our concept of reaching out,” Rodriguez said.

For now, for the Bantayog women, innovating meant literally thinking outside of their cramped box.

From their archives, they printed out newspaper scans and stuck them onto illustration boards, wrapped them in plastic cover, then propped them up on stands lined near the monuments. The canopy of the towering bodhi trees served as their shade. It was the beginning of Bantayog’s garden exhibits.

The project was far from being viral, but the women cherished every mind that remembers. On that hot day, teachers came to visit.

“In the long term, I have no doubt – I have no doubt that the Marcoses will lose because we have the truth…,” Rodriguez said. “In the short term, we will lose some of the battles.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Closer Look] ‘Join Marcos, avert Duterte’ and the danger of expediency](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-trillanes-duterte-expediency-june-29-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] A Freedom Week joke](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/20240614-Filipino-Week-joke-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[In This Economy] Marcos’ POGO ban is popular, but will it work?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-marcos-pogo-ban.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] POGOs no-go as Typhoon Carina exits](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-graphics-carina-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=424px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Hindi ito Marites] First Lady Liza Marcos: Unofficial presidential spokesperson?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/Hindi-ito-Marites-TC-ls-02.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Newspoint] A fighting presence](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-a-fighting-presence.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=441px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] If it’s Tuesday it must be Belgium – travels make over the Marcos image](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-travel-makeovers-marcos-image.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Raised on radio](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/raised-on-radio.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=396px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] Marcos: A flat response, a missed opportunity](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-marcos-flat-response-april-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=277px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.