SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

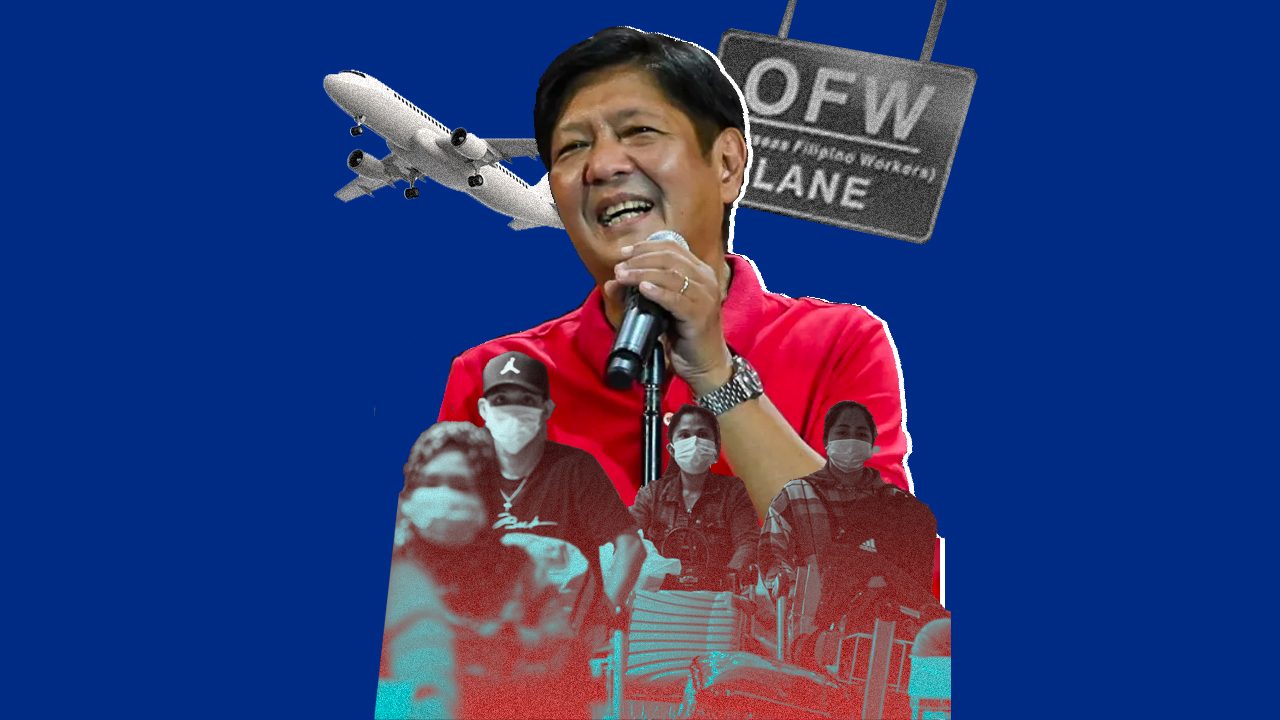

MANILA, Philippines – Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.’s landslide win in the 2022 presidential election was not only a runaway victory among Filipinos in the homeland, but among the overseas Filipino community as well – from whom he gained 475,982 votes.

His closest opponent, outgoing Vice President Leni Robredo, was hundreds of thousands of votes away with 139,798.

There’s no missing the irony. The hardships experienced by overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) and their dreams of coming home are tales that are all too familiar, and Marcos Jr.’s father was a large factor in millions of Filipino families being separated by labor migration.

Under the term of the senior Marcos, labor export became a pillar of economic development. While the exodus of Filipino migrants in the 1970s and 1980s searching for work abroad was linked mostly to economic reasons, some could attest to escaping the human rights situation as well.

Marcos Jr. has expressed his plans to export workers, just like his father did. What changed in more than three decades?

Labor export and activism from afar

In 1974, Marcos and his technocrats developed the labor export program due to an increasing number of highly educated Filipinos unable to find work locally. The Philippine economy had a limited capability to employ highly skilled labor. Exporting labor would also allow for the generation of revenue through remittances from abroad.

According to James Zarsadiaz, director of the Yuchengco Philippine Studies Program at the University of San Francisco, the mass migrations of Filipino workers during this time was a “perfect storm” of factors: more Filipinos wanted to pursue economic opportunities abroad, and some were escaping the economic and political situation in the country that arose from the dictatorship.

In the case of the United States, where around 300,000 Filipinos migrated during the Marcos era alone, immigration restrictions had also relaxed with the 1965 Hart-Celler Act. In the Middle East, rising oil prices in the mid-1970s caused an increase of contract labor from the Philippines.

Meanwhile, an anti-Martial Law movement grew in some areas in the US while the dictator was still in power.

“Filipino immigrants throughout the United States were outraged at what many believed were policies and actions undermining the integrity of the Philippines and its people living around the world,” Zarsadiaz wrote in a 2017 piece.

Activist Filipinos living in America put up organizations, such as the National Coalition for the Restoration of Civil Liberties in the Philippines and the Katipunan ng mga Demokratikong Pilipino, to oppose Martial Law and the US’ support for Marcos. According to University of the Philippines political science professor Jean Franco, Marcos put up the Commission on Filipinos Overseas originally to target progressive migrants.

“The reason why Marcos did this was because he was aware that the primary opposition figures during that time were already in the US, and of course he was aware that the opposition was already planning its moves on how to either field a candidate for future election, or anything that would weaken Marcos’ hold on the Philippines at the time,” Franco said in a September 2021 interview with Rappler.

Not all Filipinos in America were critical of Marcos, but the foreign-based activism grew with “ethnic newspapers,” Zarsadiaz told Rappler in a May 2022 interview. The underground movement in the Philippines sent letters to immigrants, informing them about the atrocities via newspaper clippings. Immigrants would then inform the community by producing ethnic newspapers.

“It was about putting international pressure [on the Philippine situation]…. But the concern among Filipinos in the Philippines, and even those who moved [to America] was that they could lose touch with what’s happening in the Philippines. And this was one way to kind of keep in touch with the homeland – keeping up with Philippine politics or what Marcos was doing under Martial Law,” said Zarsadiaz.

Over time, according to a 2014 Massachusetts Institute of Technology study, labor export was normalized due to demand for remittances, a developing private recruitment industry, and the creation of more government agencies that catered to OFWs.

According to Franco, labor export eases pressure on the government to create enough jobs locally. Franco also said the government would also feel less burdened to provide services because OFWs would be able to provide those for their families.

“What economists are saying is, if you are too reliant on labor export, you are not creating enough wealth. It’s not sustainable wealth,” Franco told Rappler in January 2022.

Even with a documented history of opposition against the Marcoses among Filipinos in the US, Marcos Jr. won the election among the community nearly four decades later. Here, he garnered over 35,000 votes, more than double the support he got from the community in the 2016 vice presidential race. The community flipped as it once helped Vice President Robredo reach her victory with 18,407 votes against Marcos’ with 14,193 votes in 2016. In 2022, Robredo got 32,319 votes in the US.

Many Filipinos today find themselves migrating out of need and not want, even risking their lives with illegal recruiters or going to conflict-ridden countries just to provide for their families.

Continuity and support

Part of the reason why Marcos Jr. had massive overseas support was because he was seen to be a continuity candidate for the still-popular President Rodrigo Duterte. With Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte, daughter of the outgoing president, running in tandem with Marcos, support for the “Uniteam” was amplified among Filipinos locally and internationally.

The “only reason” Josh Leron, an OFW who has spent 14 years in the United Arab Emirates, supported Marcos Jr. was because he believed he was the best candidate to continue Duterte’s legacy.

Leron’s group, OFW Global Movement for Empowerment (OFWGME), supported Duterte’s presidential bid in 2016, and originally wanted Sara to be the next president. “Since Sara did not push through with running for the presidency, we looked for a candidate whom we felt would continue President Duterte’s good projects,” he said in Filipino.

“Aminin ba natin o hindi, talagang may mga magagandang proyektong ginawa si President Duterte na nakatulong din sa Pilipinas. Unang-una na diyan ‘yung, hindi man nawala, pero nabawasan talaga, ‘yung droga. Sa lugar namin [sa Batangas], kahit ‘yung mga drug addict doon, mga tambay doon, magsasabi mismo na nabawasan,” he said.

(Whether we admit it or not, President Duterte has accomplished good projects that have helped the Philippines. The first would be illegal drugs – even if they have not been eliminated, they are less rampant. In our area in Batangas, even the drug addicts and loiterers would say that drugs are not as rampant anymore.)

Leron also praises Duterte’s Build, Build, Build project – an admiration coming from his “amazement” at Dubai’s “nonstop” push for infrastructure development that he has observed while working in the country.

Over in Taiwan, where Marcos got a whopping 90.2% of the votes for the presidency, organized Filipino groups – such as FilCom, OFW Partylist Taiwan, and OFWGME – received much support from Marcos-Duterte camps and party-list groups to participate in labor sector initiatives by the Manila Economic and Cultural Office.

Combating disinformation, and shortcomings of the Robredo camp

Disinformation and revised history peddled by the Marcos camp spread among OFWs as well. Overseas supporters of Robredo found it difficult to counter the lies. (READ: Election disinformation efforts target to damage Robredo’s image, boost Marcos Jr.’s)

Johanna Zulueta, a member of Team Leni Robredo Japan and Solid Leni-Kiko Global, said members of the groups who tried to engage with Marcos supporters were often unsuccessful in convincing them to consider their candidate. Zulueta said the other side remained loyal to Marcos for reasons that included how they benefited from the past Marcos administration, a desire to continue the Duterte legacy, and how some even “identified” with Marcos as a victim of demonization.

“’Yun ang strategy [ng Robredo supporters]: paninira. Eh, kay BBM, kahit ano ang ibato sa kanya, hindi niya pinapatulan. Kung totoo man ’yun o hindi, wala namang napatunayan, hindi naman siya nakulong. Crab mentality,” said Rose Lei Valdez, a web developer based in Dubai. (READ: Kung talagang nagnakaw ang mga Marcos, bakit wala pa ring nakukulong sa kanila?)

(That is the strategy of the Robredo supporters: vilification. Meanwhile, BBM [Bongbong Marcos], no matter what criticism is thrown at him, he does not entertain it. Even if the criticism is true or not, nothing has been proven, and he has not been detained. [That is] crab mentality.)

But the Marcos family’s billions of pesos in stolen wealth and the human rights abuses during the dictator’s regime have been proven time and again by historical records and the courts in the US and the Philippines. The Marcoses’ whitewashing campaign has peddled a narrative that they were unjustly ousted by rebels, even if Martial Law victims included not just activists but also doctors, teachers, journalists, and their families.

@rambotalabong Klaruhin natin, Senator Imee. #marcos #marcosfamily #phhistory #kasaysayan #rappler #phnews #newsph #neverforget ♬ original sound – Rambo Talabong

“Too much, too much,” Saudi Arabia-based OFW and Robredo supporter Cezar Tionko said of the amount of fake news he saw on his social media.

Tionko, advocacy chairman of a Middle Eastern chapter of the Liberal Party, said that many OFWs got their fix of current affairs on social media and the internet, which was where Marcos disinformation had concentrated.

“I have a lot of friends who have been trying to gather people to tell them the truth, but their machinery is just ahead of us,” Tionko said. “They were slowly given the wrong information that we weren’t able to control as the opposition.”

Tionko struggled to say that the “kakampinks” failed to do enough in the campaign. He believed they did what they could for Robredo, and fought a good fight for her.

“Whatever Leni says is dismissed as falsehood to them. So how do we fight the lies? By giving them the truth. But sometimes when these people are already brainwashed, it’s hard. Their truth is different already. Gaslighting is when their truth is already the lies,” said Tionko.

Zulueta had a different take – the opposition was caught up in its echo chamber, according to her. One way the overseas Robredo supporters in her circles tried engaging with voters was through lectures about history and the truth about the Marcoses.

In retrospect, she realized that these may have been “too elitist” and “too cerebral.” They were preaching to the choir, as some members were even averse to inviting Marcos supporters to the lectures because they belonged to the other side.

“[The lesson learned] is that there is a need really to reach out to the supporters because we have this tendency to think, ‘If you’re not with me, if you’re supporting a different candidate, if you think differently, then you’re different. I don’t want to talk to you anymore.’ I think it’s very divisive, and I saw that for the past six years,” Zulueta said.

Moving forward, Zulueta said the opposition should be making better use of social media to beat them at their own game. It’s an opportunity for the opposition Filipinos in Japan, where there are vloggers among the community, she said.

‘Forgiveness’

Lies and propaganda alone did not cement OFWs’ support for the Marcos and Duterte families. After all, Duterte delivered on numerous promises to the sector.

As early as his 2016 campaign, Duterte had promised a dedicated department for OFWs to lessen the hassle of going to numerous agencies for requirements. It took the final months of his administration to get it approved, but it was done. The Department of Migrant Workers is set to be fully operational by 2023.

It was also under Duterte’s watch that the construction of an OFW hospital was completed in Pampanga. The first-of-its-kind hospital, expected to begin operations by June 2022, will cater to OFWs and their dependents.

“[Duterte] has set the bar so high when it comes to OFW protection and welfare. We saw that during the pandemic. And he will always be the tatay of our OFWs, because there is that emotional connection to him – our OFWs believe in him, in his leadership,” said long-time OFW advocate Susan “Toots” Ople in a May 30 Rappler Talk interview. Marcos Jr. has chosen her as his migrant workers secretary.

Marcos’ presidential campaign included a seven-minute video dedicated to his plans for OFWs and their families. Among other plans, Marcos promised the law creating the OFW department would be implemented as soon as possible, and there would be more OFW hospitals in every region.

“I’m pretty confident in the incoming administration. We will strive to do our best for our OFWs and their families as well,” said Ople.

According to Zarsadiaz, Marcos’ win was not just a product of revised history – it also involves a “level of forgiveness” that some Filipinos have for the incoming first family.

“I think the forgiveness is also just a by-product of [the passage] of time…. It’s not necessarily softening up to the Marcos family, I think it’s kind of like, ‘Well, this is the son, and he has to chart his own future,’” said Zarsadiaz. – with reports from Lian Buan and Jojo Dass/Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[New School] Why majority of overseas Filipinos in Taiwan support Marcos](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/05/bbm-supporters-taiwan-may-19-2022.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

![[New School] Tama na kayo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/new-school-tama-na-kayo-feb-6-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=290px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] Marcos’ POGO ban is popular, but will it work?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-marcos-pogo-ban.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] POGOs no-go as Typhoon Carina exits](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-graphics-carina-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=424px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.