SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Renato Villaran, 67, remembered crying when he received in July this year the title endowing him 6,000 square meters of farm land in Naic, Cavite. He said it’s the first time he’s had anything under his name.

“Napakalaking bagay po ang naitulong ng lupa na ‘to sa amin,” Villaran said, his voice breaking at the other end of the line during a phone interview with Rappler. “Nasa akin na po ang CLOA (Certificate of Land Ownership Award). Napaiyak po ako. ‘Di ko akalain na mabibigyan ako noon.”

(The land awarded to me has been a big help to my family. I now have the CLOA. I cried. I never thought I would be given land.)

Villaran is one of the agrarian reform beneficiaries of the New Agrarian Emancipation Act signed this July.

Farming is the way of life he inherited from his parents. Villaran finished high school, went to work on the farm, and had four children, all of whom now have their own families. These days, it’s just him and his wife minding the farm, cultivating mango, banana, and star apple trees.

After around four decades of farming, it’s the first time for him to own a piece of land, he said. The land he received may be small – as it doesn’t even amount to a hectare – but Villaran is grateful nonetheless.

“Maraming salamat kay Pangulong Bongbong at sa mga nangangasiwa po sa DAR (Department of Agrarian Reform),” Villaran said. (Many thanks to President Bongbong and the officials of the DAR.)

A presidential promise fulfilled

One year after he swore to free agrarian reform beneficiaries of unpaid amortizations, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. went back to Congress in his second State of the Nation Address (SONA) to report a promise fulfilled.

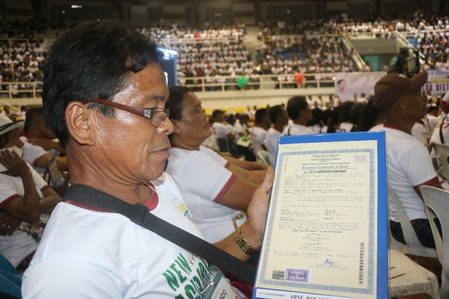

With the passage of the New Agrarian Emancipation Act, Marcos relieved 610,054 farmers of their loans totaling P57.65 billion. When Marcos signed the law on July 7, 32,441 land titles were also awarded to 27,132 beneficiaries nationwide.

This law was considered good news and, according to Agrarian Reform Secretary Conrado Estrella III, it was even given the moniker “happy law.”

Marcos thanked Congress for the swift approval of the law. “Sa ngalan ng mga magsasakang ito at ang kanilang mga pamilya, maraming salamat muli sa ating mga mambabatas,” said Marcos on July 24. (On behalf of farmers and their families, thank you to all our lawmakers.)

The government touted this as a victory that signifies prioritizing public interest despite the government’s financial constraints.

“There is a time when the government needs to balance interest between efficient use of resources for certain priority concerns…and the concerns of social justice,” said Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) Undersecretary Marilyn Yap in an interview.

“Land reform is 51 years in the country and it’s been a long time. It is about time that this is done. I think this administration just put down its foot and assessed it for real,” Yap added.

But Yap also admitted the law does not completely free farmers from the bondage of the soil, considering the poverty of farmers exacerbated by the pandemic.

Farmers remain to be among the poorest sectors in the Philippines. Beset with many long-standing issues such as land conflicts, land productivity, outdated technology and practices, the sector needs more than condoning of loans to truly emancipate them.

Fears of selling land

Many groups critical of the government’s agrarian reform said the law was a welcome development but it also triggered concerns that it may not achieve its intended purpose.

Some groups raised the threat of land conversion. Raul Montemayor, national manager of the Federation of Free Farmers Cooperatives, said farmers may sell their land now that they are free from debt and encumbrances. If they sell to real estate firms, for instance, lands may be converted to non-agricultural uses. This does not only harm the farmer, it would also hurt the agricultural sector trying to raise productivity and domestic growth.

The agrarian reform secretary, however, assured the public that farmers, even with condoned loans, will not be able to sell or transfer their land except through hereditary succession. This is a provision in the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law (CARL) that was retained in the emancipation law.

“It is provided for in that law that you cannot sell your land from the time you have received your title. You cannot sell it for a period of 10 years,” said Estrella in an interview last July. “Only after 10 years can you sell your land to private entities.”

If they find beneficiaries who breach this provision, the DAR will have to get the land back and “distribute it to other more deserving agrarian reform beneficiaries,” Estrella said. “It’s simply that way.”

Leonardo Legaspi, one of the beneficiaries who attended the ceremonial awarding of titles at Heroes Hall in Malacañang, said he had no plans of selling his land.

A farmer from Cavite, Legaspi was awarded two hectares of farm land. Like Villaran, he was grateful for what was given to him. He said he hopes other farmers would experience this too.

“Siyempre masayang-masaya po na wala kaming ginastos,” Legaspi told Rappler in a phone interview. “Sana mag tuloy-tuloy. Sa bukid namin, madami pang kailangang ayusin.”

(We’re happy because we didn’t have to spend anything. I hope this continues. In our land, there are many things to smoothen out.)

Condemning the landed poor

But farmers hindered from selling their land is not the good news the measure was trumpeted to be, economist Calixto Chikiamco said.

“Farms will be frozen out of the rural land market for 10 years and prevent any form of farmland consolidation through leasing. More efficient farmers cannot expand through leasing,” Chikiamco wrote in February.

Farms have been shrinking in size as small-scale farmers, cultivating less than three hectares of land, dominate the sector. Under the CARL, beneficiaries cannot own more than five hectares of land. Children of agrarian reform beneficiaries can inherit only up to three hectares.

Land consolidation is supposed to help improve agricultural yield and management of farms, but this won’t happen if farmers do not have the option to sell. The law “effectively chains the farmer-beneficiaries to the land and condemns them into poverty,” Chikiamco said.

Issues in productivity, resources

The law could thus lead to more landed but still poor farmers if there isn’t enough support in terms of resources and technology, Jayson Cainglet, executive director of Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura, told Rappler.

Cainglet said one of the immediate concerns of beneficiaries is the cost of production aggravated by high prices of fertilizers and fuel.

Productivity is also affected by the quality of soil. Last May, the Department of Agriculture said that majority of farmlands in the Philippines have moderate to low soil fertility due to unsustainable agricultural practices and the use of synthetic fertilizers. Low soil fertility means low crop yields.

Estrella remains optimistic of the law’s impact on farm productivity.

The agrarian reform secretary maintained that the emancipation law will encourage farmers, now free from debt, to improve methods, modernize, and mechanize. They can even be incentivized to form cooperatives and consolidate lands. Estrella said that if these are done, the Philippines will no longer have crop shortages and can do away with rice importations.

“In the rice lands, if they form themselves in a cooperative…then they can address a lot of things,” Estrella said. “They can save up with the inputs and they will be earning more and they would be producing more if they use the modern and the more scientific methods. And if they do that there will be greater production and that will lead us away from rice shortage.”

What’s clear, early on, both from the government and farmers’ groups, is that the condonation of beneficiaries’ loans was a long time coming.

The Philippines’ agrarian reform program has dragged for decades. Thirty-five years after the implementation of the program – a “gargantuan sacrifice in the name of asset equity,” as national scientist and economist Raul Fabella wrote in 2017 – land distribution is almost complete.

But he said it has also created a new class of landed but poor agrarian reform beneficiaries who own farms but do not have the means to increase yield and enhance skills and resources.

Efforts like the New Agrarian Emancipation Act are almost always after-the-fact. Beneath the so-called “happy law” is the dead weight of agrarian reform in the country, the splintered lands under constant threat of development, and the poverty of aging Filipino farmers. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[ANALYSIS] How one company boosts farmer productivity inside the farm gate](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/bioprime-farmgate-farmer-productivity-boost.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=465px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.