SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

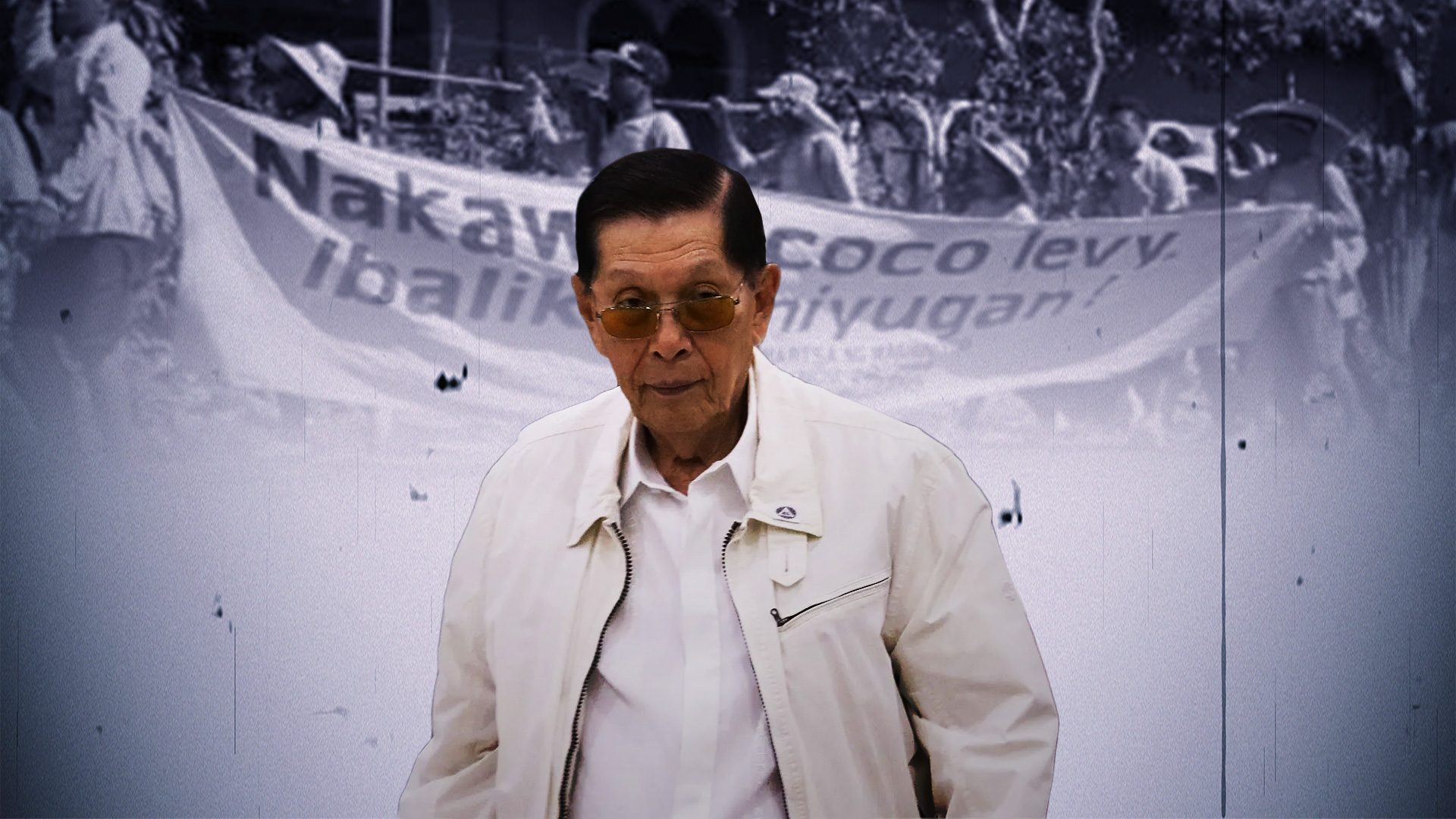

MANILA, Philippines – Exactly six days before his 99th birthday, Chief Presidential Legal Counsel Juan Ponce Enrile was cleared by the Supreme Court’s (SC) First Division of his graft charge in relation to the coco levy fund scam.

Enrile turned a year short of a hundred on Tuesday, February 14.

The case was filed by the Office of the Solicitor General, on behalf of the state, in 1990. The case stemmed from the state’s petition claiming that businessman Eduardo M. Cojuangco Jr. took advantage of his relationship with late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos and reaped gains “through the issuance of favorable decrees.”

Enrile, along with his other co-accused, was slapped with the charge after serving as board members of the United Coconut Planters Bank. According to the petition, Enrile and other board members allegedly allowed a decision of a board of arbitrators to lapse, resulting in the alleged transfer of P840 million to Cojuangco’s company.

Other co-respondents, Cojuangco Jr., Jose R. Eleazar Jr., Maria Clara Lobregat, and Augusto Orosa all died before the case reached final judgment. The criminal charges against the four were dismissed because their death “terminates their criminal liability without prejudice to the right of the State to recover unlawfully acquired properties or ill-gotten wealth,” the High Court said.

For Enrile, the case against him was dismissed due to the violation of his right to speedy disposition of case.

What do the laws say?

In explaining the right to speedy disposition of case, the SC listed constitutional provisions, laws, and related jurisprudence.

Article III, section 16 of the 1987 Constitution explicitly states that all persons have the right to speedy disposition of cases “before all judicial, quasi-judicial, or administrative bodies.” Since the Office of the Ombudsman was also tagged in the case, the SC also noted the Ombudsman is required to promptly act on all cases filed before it under Article XI, Section 12 of the Constitution.

“The Ombudsman and his Deputies, as protectors of the people, shall act promptly on complaints filed in any form or manner against public officials or employees of the Government, or any subdivision, agency or instrumentality thereof, including government-owned or controlled corporations, and shall, in appropriate cases, notify the complainants of the action taken and the result thereof,” the provision read.

The Ombudsman initially dismissed the graft complaint against Enrile and his co-respondents on the ground of prescription – or the period within which legal action can be taken against an alleged offense. This led to the case going all the way up to the High Court.

In addition, the SC also mentioned Section 13 of Republic Act No. 6770 or the Ombudsman Act of 1989, which lays down the Ombudsman’s mandate:

“The Ombudsman and his Deputies, as protectors of the people, shall act promptly on complaints filed in any form or manner against officers or employees of the Government, or of any subdivision, agency or instrumentality thereof, including government-owned or controlled corporations, and enforce their administrative, civil and criminal liability in every case where the evidence warrants in order to promote efficient service by the Government to the people.”

Lastly, the High Court cited Cagang v. Sandiganbayan, where the SC laid down guidelines in resolving cases involving the right to speedy disposition of case. The rules include the distinction between the right to speedy disposition of cases and the right to speedy trial.

The SC said the right to speedy trial may be invoked in criminal prosecutions against courts of law, while the right to speedy disposition of cases may be invoked before any “tribunal, whether judicial or quasi-judicial.”

Recently, Enrile’s former chief of staff, Gigi Reyes, also scored a win in the same SC division. Through the petition for a writ of habeas corpus, Reyes was temporarily released by the SC on the basis of her right to speedy trial.

Violation of constitutional right

In its decision, the SC said it found that the Ombudsman had violated the right of Enrile and other respondents to speedy trial due to the inordinate delay in concluding the preliminary investigation. The High Court even presented a timeline showing how long it took for the case to move from the time the complaint was filed in 1990.

“Based on this timeline, it is apparent that the preliminary investigation spanned for over eight years. It was only in 1997 that any movement or action on the case actually began,” the High Court explained.

The SC also noted that in Lorenzo v. Hon. Sandiganbayan Sixth Division, there was a violation of the constitutional right to speedy disposition of cases as the preliminary investigation spanned four years from the filing of the complaint.

Meanwhile, the Ombudsman’s Administrative Order No. 1, series of 2020 states that preliminary investigation shall not exceed 12 months or one year for simpler cases, and 24 months or two years for complex cases.

In the decision, the High Court said the preliminary investigation started on February 12, 1990 and ended on October 9, 1998 – eight years.

“Thus, whether .the Court applies the 10-day period in Javier and Catamco, or the more generous periods of 12 to 24 months under A.O 1, we arrive at the same conclusion that the Ombudsman exceeded the specified period provided for preliminary investigations.”

‘Disadvantages’

In explaining why the case was dismissed, the SC also cited the “tactical disadvantages by the passage of time.”

“Certainly, if this case were remanded for further proceedings, the already long delay would drag on longer. Memories fade, documents and other exhibits can be lost, and vulnerability of those who are tasked to decide increase with the passing of years. In effect, there would be a general inability to mount an effective defense.”

The court explained that it has no doubt that the state has all the resources to pursue corruption and ill-gotten wealth cases, but the delay in Enrile’s case “may have made the situation worse for respondents.” – Rappler.com

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[OPINION] What kind of citizens are we?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/tl-what-kind-of-citizen-are-we.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=333px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

Judicial inefficiency: Not a bug, but a feature in post-Sereno judiciary.