SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Last of 2 parts

Part 1 | In prison, mother and baby share P85 a day for food, medicine

Editor’s Note: This story is based on an original submission by Ateneo de Manila students Angeline Braganza, Allison Co, and Iana Padilla for their investigative journalism class.

When overseas Filipino worker Rose* took a vacation to the Philippines in 2003, she had every intention of returning to Dubai. She had already worked almost two decades as a house maid, but her children still had dreams to fulfill.

With three kids she needed to get through school, Rose took on some side hustles in an office and a hospital. They graduated college by the time she went on that vacation, and later on one became a dentist, another, a physical therapist, and the third, a computer engineer.

But Rose never got to return to Dubai, nor was she able to see her college graduates turn into professionals. Today, she is an elderly person deprived of liberty (PDL) taking care of the women and babies in the mothers’ ward of the Correctional Institution for Women (CIW). But she remembers all too well the events that led to her life sentence in prison.

It was around 1 am on November 20, 2003, she said, when cops entered her house in Pasig looking for her husband. He apparently became known to law enforcement as a drug dependent.

“Why are you looking for my husband, sir?” she recalled asking them.

As soon as the cops spotted her, they turned towards her.

The police arrested her for a charge which turned out to be connivance in drug usage. “What did they mean, connivance? I didn’t have any drugs on me. I also turned out negative on my drug test. Well, it just so happened that it was my house [that my husband was using].”

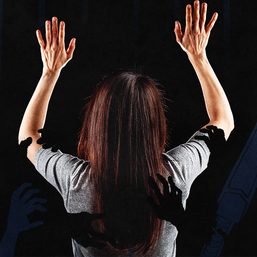

“My grandchild and adopted son just happened to be there. They were crying, but I could not bring myself to cry, because I was in shock…. I fought the police. Sad to say, the police harmed me. And I hated that my adopted son saw the police hurt me,” she said.

Rose’s husband was home, asleep. But they were both arrested and taken to a Pasig jail.

Two years later, both were convicted to life in prison. Her husband went to the New Bilibid Prison, while she went to CIW, full of resentment towards him. Her role as a mother was snatched from her, never to be returned.

“What hurts is how long I was away from [my children’s] side. And now, I’ve been in prison for another 20 years. I’ve been away from them for 40 years now,” she said.

Rose has learned to live with peace in her heart. Her resentment towards her now-deceased husband has subsided, and she is proud of her kids who had grown up to live their lives in Dubai together with their own children.

The family she now has is found in the CIW mothers’ ward. She plays a vital role there, where she has been assisting in the care of both PDLs and babies since 2010 due to the lack of medical personnel who can monitor them at all times.

The women tell her that their babies are her “grandchildren.”

Along with the toys for these “grandchildren” on a shelf of the mothers’ ward is a purple, polka-dotted go-bag with baby garments that don’t belong to any one baby. They are worn by the infants who come and go. The bag is there for any woman in the mothers’ ward who has to be rushed to the hospital to give birth. It is Rose who packs it.

Rose has it ready all the time because pregnant women who enter the prison often aren’t prepared with the clothes their babies will wear. It was also Rose who loaned Maria* the P3,000 she needed for her ultrasound from the extra money she had in her pharmacy deposit.

No baby birthdays in CIW

The women in the mothers’ ward at the CIW have the option to keep their newborn babies with them. This is somewhat of a privilege, compared to what some incarcerated mothers have to go through, like Reina Mae Nasino.

When mothers in prison have such an option, the assumption is that they’d prefer to maximize that time with their babies as much as possible. But with an uncertain future and feelings of being ill-equipped to care for their babies, some mothers choose to let their babies out early.

CIW rules say that when a PDL under their care gives birth, the babies may stay with the mothers for a maximum period of one year. But according to lone resident doctor and Corrections Technical Chief Superintendent Maria Lourdes Razon, at least in her past year working at CIW, there are no babies who have celebrated their birthdays in the facility.

Rita*, 32, is one of the four mothers – three with newborns and one still pregnant – housed in the CIW’s mothers’ ward as of mid-March. She has the tiniest and youngest of the three babies, but Rita knows that she is set to give her up soon.

Her family has decided that her uncle, who is based in the US, would take her baby when she is three months old with hopes she will live a better life in America. She has around two months left before that happens.

“I already have three children, and this is my fourth. My brother has been taking care of my first three and sending them to school. But he told me that he cannot handle a fourth,” said Rita.

“It’s painful. I was expecting my partner to take her. But unfortunately, he’s already found someone else to be with in the outside world,” she added.

Rita is only starting her eight-year sentence in prison for drug-related charges. She hopes that one day she will be able to visit her child in the US.

“They told me that they will still raise her knowing that I am her mother,” she said.

Rights of incarcerated women

The United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders, also known as the Bangkok Rules, is a set of 70 rules focused on the treatment of female prisoners, including pregnant PDLs. Under these requirements, the mother and the child’s time together must be “made in the best interests of the child.”

In Malaysia, prisons’ regulations provide that a child under the age of three may be admitted with his or her mother and the child should be provided with basic necessities and care by the director general.

Meanwhile, in Thailand, specifically the Central Women’s Correctional Institution in Lat Yao, there is not only a mothers’ ward but also a designated nursery for newborn babies. The babies are taken care of by the nurses of the facility.

Lawyer Gian Taruc from the Visitorial Division of the Commission on Human Rights pointed out the disparity among the Philippines’ regional members.

“In other countries that are equally Third World countries too, like Malaysia and Bangkok, they are able to implement these programs. They have policies that allow them to give proper care for female PDLs. So why not in the Philippines?” he said.

The deficiency of mental support for mother PDLs is a persisting reality even beyond the walls of CIW. Nasino also cited similar psychological harassment inside the Manila City Jail where she was detained.

“From my experience [in Manila City Jail] when I gave birth, there was this condemnation from the guards blaming me for the situation of my baby. They would tell me: ‘It was you who got yourself imprisoned, so why should you rely on us for your pregnancy?’ This is why other PDLs who feel unwell would opt not to say anything instead,” she said.

In a study conducted by the Philippine Council for Health Research and Development, 15.6% of Filipino women experience depression during pregnancy and 19.8% after childbirth.

Not ashamed

Rose does not allow the women under her care to mingle with the general, congested population. It’s a precaution to keep the mothers and babies healthy. Most of the time, the babies do not have access to vaccines.

The unavailability of vaccines was the very first reason Maria cited why she did not plan to keep her baby in the facility for up to a year. Maria also eyed transitioning her baby from breastfeeding to bottle feeding so that her family outside wouldn’t have a difficult time feeding him. Health experts have long cited breast milk as best for healthy infants.

With some solitude in the mothers’ ward, the women have time to reflect on what they plan to tell their babies about themselves as they grow older. For them, accountability for their crimes lies with them, and their babies need not worry about their mothers’ past mistakes. Women at the Bureau of Corrections (BuCor)-supervised CIW are convicted with sentences no less than three years and a day.

“I will not be ashamed to tell my child what happened to me,” said Maria, who also faces drug-related charges. “I’ll tell him the truth, that I had him here with me. I’d rather he finds out from me than anyone else. I gave birth to him [while detained], he met so many people here, and he was a Baby BuCor.”

Rita had similar sentiments about not being ashamed to tell her daughter one day. “It was not them who made the mistakes, but us.”

Jasmin*, the only pregnant PDL at the ward, wants to wait until her children are mature enough to understand what she had gone through. Apart from the baby she was carrying in her womb, she also has a three-year-old with her family.

“I will wait until they’re old enough. It will be difficult for me to explain when they might not understand. My three-year-old doesn’t know that I’m here, and thinks that I’m just working,” said Jasmin, who is serving a sentence for theft.

Better care for mothers

In the House of Representatives, the Makabayan bloc filed House Bill No. 570, or the Parents in Jail bill.

Nasino’s case is particularly cited in the bill’s explanatory note. It highlights the need to provide prisoners, especially mothers, the necessary mechanisms and facilities to enjoy their parental rights and ensure that the needs of their children are attended to while they are incarcerated.

HB No. 570 stresses that facilities must strictly comply with Republic Act No. 11148, or the Kalusugan at Nutrisyon ng Mag-Nanay Act, which covers nutritional needs of both mother and child, as well as the availability of prenatal and postnatal care for mothers and other medical needs of the child.

The bill also proposes “child-friendly visitation programs” that mandate the establishment of special visitation rooms in prison facilities for solo parents and their children.

Budget increases would be crucial for the better treatment of mothers, and the medical needs of PDLs in general at the CIW, according to Razon.

If the CIW had their way, each PDL would have a minimum P100-medicine budget per day, Razon said.

More could be done for the mothers at CIW, who already have decent living conditions – and more so for mothers in jails who don’t even have that shelf of dusty toys, or their own ward.

While Rose is happy to take care of her “grandchildren,” questions remain if she would have been assigned there if there were enough medical personnel to tend to them.

“In any case, I’m here. I’m here to supervise, to help, in any way I can,” she said. – with reports from Angeline Braganza, Allison Co, and Iana Padilla/Rappler.com

*Names have been changed.

All quotes have been translated into English.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler Investigates] What’s it all about, Alice?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/alice-guo-newsletter-may-30-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=292px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Drug arrest and jail and prison congestion: Search for alternatives](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/tl-drugs-prison.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=391px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Dash of SAS] Making abortion a constitutional right](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/Its_true_-_Flickr_-_Josh_Parrish-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=125px%2C0px%2C768px%2C768px)

![[OPINION] Unpaid care work by women is a public concern](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/20240725-unpaid-care-work-public-concern.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[DECODED] The Philippines and Brazil have a lot in common. Online toxicity is one.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/misogyny-tech-carousel-revised-decoded-july-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Why women seek divorce](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-women-seeking-divorce-june-14-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.