SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

First of 2 parts

Editor’s Note: This story is based on an original submission by Ateneo de Manila students Angeline Braganza, Allison Co, and Iana Padilla for their investigative journalism class.

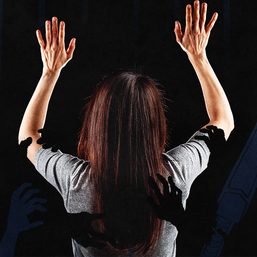

In October 2020, activist Reina Mae Nasino, surrounded by cops, wrapped up in full protective gear, and wearing handcuffs, attended her baby’s funeral.

Nasino and her baby River became icons of injustice, not just of the crackdown on dissent during the Duterte administration, but of the conditions of detained mothers who simply want to care for their newborn babies. Baby River was separated from Nasino at birth, and died when she was only three months old.

“I would randomly wake up, tears welling in my eyes. And then, I would find myself embracing the last shirt my baby wore,” Nasino said in a recent interview. In 2023, she was acquitted of charges pertaining to illegal possession of firearms and explosives.

Nasino, who spent most of her pregnancy in the Manila City Jail, is just one of the countless mothers in the Philippines who enter prison with a baby in their wombs. Over in Mandaluyong, there is a 21-square-meter room in the Correctional Institution for Women (CIW) called the mothers’ ward.

Here stay persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) who are pregnant, or had just given birth. The mothers’ ward consists of six beds, a shared bathroom with curtains serving as a door, a meager pantry, faded stickers of cartoon characters on the walls, and a shelf of dusty toys.

Maria*, 34, was once among the expectant mothers – she entered CIW eight months pregnant in September 2023. The following month, she gave birth to a baby boy. While she felt delighted to welcome this little drop of joy into her life, she couldn’t cope with the storm of financial demands that assaulted her. Maria had to borrow money from a fellow PDL to cover her ultrasound sessions, check-ups, and laboratory fees.

The Bureau of Corrections (BuCor) has a measly P15-medicine budget per PDL, per day. According to lone resident doctor and Corrections Technical Chief Superintendent Maria Lourdes Razon, this already accounts for everything medical – from medicines to medical supplies like cotton balls and alcohol, and even period products. There’s no separate budget for a PDL who is pregnant or ill.

In CIW, according to Razon, PDLs who have prescription medicines have to deposit in the pharmacy whatever money is provided by their families. The pharmacy then deducts from the fund whatever medicines PDLs avail of.

When needed, and especially for births, CIW’s pregnant PDLs are referred to the Mandaluyong City Medical Center (MCMC), a stone’s throw from the prison. Razon claimed that the PDLs who need procedures need not shell out any money, as it is a public hospital. But such does not seem to be the case – if Maria’s experience is any indication.

Maria was lucky that her fellow PDL had an extra P3,000 she could spare from the money deposited in the pharmacy.

Inadequate resources

A shortage of resources and medical staff compromises the quality and accessibility of healthcare services, particularly in terms of prenatal and postnatal care. This situation forces pregnant PDLs to bear the financial burden of medical expenses, as Maria herself experienced.

As of March 2024, the CIW has a population of around 3,100, but, according to Dr. Razon, the facility is meant to house only 1,000.

Besides Razon, there are only 13 nurses to tend to the over 3,000 PDLs in CIW, translating to one nurse for every 231 women, with no obstetricians, gynecologists (OB-GYN), nor midwives.

The CIW shares a line item with the New Bilibid Prison (NBP) in the BuCor’s budget. From the P5.2 billion budget the NBP and CIW shared in 2023, their budget was cut down to P4.72 billion in 2024. But NBP likely takes a significant share. The notoriously overcrowded men’s prison housed around 30,000 by end-November 2023 – 10 times as many as the population in CIW.

If one were to assume that CIW takes 10% of the budget, that leaves just P472 million for the CIW in 2024. This already accounts for administrative and operational costs.

The National Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), which oversees local city and municipal jails that exclude the BuCor-supervised CIW, recorded more than 1,600 pregnant detainees and 485 births in the past two years.

On the rare times that specialists who are part of medical missions organized by non-government organizations are able to visit, pregnant PDLs get to be examined. But more often than not, they have to make do with the little that’s available.

The Commission on Human Rights (CHR) said that only 37 out of 84 women’s dormitories are equipped with a breastfeeding room, again indicating very limited access to maternal health services.

Dependent on Mandaluyong City MC

According to Dr. Jonelle Baloloy, chief resident of the MCMC OB-GYN ward, PDLs who come to the hospital for maternal services are treated no differently from other patients, but when they need services that don’t require admission, they are prioritized in the queue since they only have limited time outside prison.

After securing permits to leave the facility, PDLs from CIW are accompanied by an escort and a nurse. There have been reported issues, however, according to Baloloy, of PDLs “having difficulties in securing permits to leave the facility.”

For example, for OB patients, she said, “their follow-up appointments are fixed, so those are easy. But since the hospital or local government unit pays for laboratory fees, the PDLs still have to go through the LGU for those appointments.”

Both CIW and MCMC assert that PDLs don’t have to shell out any money for their procedures, and if ever they do, fees are minimal, or the hospital finds a way to get the local social welfare office to pay for them. Yet women PDLs still say that what they need help the most with is still financial support.

It doesn’t help that the P15-medical budget covers the mothers only. Babies, who have their own needs like diapers, clothes, and hygiene products, are not PDLs and are excluded from the budget. While there is a separate P70-food allocation per day, or just P23.33 for a meal, pregnant PDLs and breastfeeding mothers need more because they also require special nutrition, like increased fluid intake.

“Most of the time, our food doesn’t have soup. We need more food, because we have increased appetites. Every time our children breastfeed, we go hungry,” said Maria.

The infirmary may not always be prepared to handle swift births as well.

“As much as possible, we really refer [births] to the nearest government hospital, MCMC. We are not equipped to deliver babies. Although there was one who went into labor quickly, and we weren’t able to bring her to the hospital on time. We were able to guide her through her labor. But we worry sometimes [about sudden births] since I’m not here 24/7, or if there’s a problem with the baby. We’re not equipped, because we are just an infirmary,” said Razon.

For Imelda Duras of the CHR Prevention Cluster Visitorial Division, prison medical staff should be equipped with multidisciplinary, and not just custodial, skills. Some of these skills include being able to provide psychological and social support for PDLs.

“So there should be health [personnel] – nurses and doctors – and we should have mental health professionals such as psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers,” said Duras.

Karen Bantang from the CHR Gender Division also cited the alarming concern about postpartum depression among mother PDLs. A study conducted by the Philippine Council for Health Research and Development found that 15.6% of Filipino women experience depression during pregnancy and 19.8% after childbirth. The pregnant PDLs of CIW aren’t any different.

With resources already at the bare minimum for women in the mothers’ ward, they also deal with the mental anguish of possibly not being able to live out the duties of motherhood. (To be concluded) – with reports from Angeline Braganza, Allison Co, and Iana Padilla/Rappler.com

*Names have been changed.

All quotes have been translated into English.

NEXT: Part 2 | Behind bars, giving a mother’s touch isn’t easy

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler Investigates] What’s it all about, Alice?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/alice-guo-newsletter-may-30-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=292px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Drug arrest and jail and prison congestion: Search for alternatives](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/12/tl-drugs-prison.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=391px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Dash of SAS] Making abortion a constitutional right](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/Its_true_-_Flickr_-_Josh_Parrish-1.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=125px%2C0px%2C768px%2C768px)

![[OPINION] Unpaid care work by women is a public concern](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/20240725-unpaid-care-work-public-concern.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[DECODED] The Philippines and Brazil have a lot in common. Online toxicity is one.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/misogyny-tech-carousel-revised-decoded-july-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[OPINION] Why women seek divorce](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/TL-women-seeking-divorce-june-14-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.