SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

First of 2 parts

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

MANILA, Philippines – Mikee walked us through the two-pronged life he’s been living. It’s every bachelor’s dream – or nightmare.

He has his own apartment, takes care of a dog that he bought for $5,000, and travels to cities around the world. The son of a wealthy businessman of a small town, Mikee’s social media accounts display a gallery of a privileged life of someone who appears formal, stiff, and calm.

But with just a few taps on his phone, he took us to a different side of Twitter and an unrecognizable version of himself: gay, effeminate, and as he described it, “kanal” – Filipino for sewer, which in local gay lingo means one who is crass.

Speaking to us on condition he is not named, Mikee is one of many queer Filipinos who find solace in the internet, afraid of coming out to their conservative families and neighbors. Reluctant and shy at the start of the interview, he got more animated as he described the vibrant queer community on Twitter – what he and his online friends often referred to as “gay Twitter.”

This is not a closed group but a bunch of queer users who follow and interact with each other, forming an extensive network. It’s a safe space where LGBT folks and their allies support and defend one another, anonymously or not.

Beyond this, the local gay rights movement is pushing for policies that will turn these safe spaces into a reality on the ground, through a law that punishes discrimination on the basis of one’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression (SOGIE).

The SOGIE bill’s status in the legislative mill illustrates the challenges that the queer community is facing in the country. The bill already passed the committee level at the Senate and was awaiting sponsorship for a plenary discussion, when on February 9, Senate Majority Leader Joel Villanueva succeeded in reverting it to the committee level, practically back to square one. Villanueva belongs to a religious group founded by his father Eddie Villanueva – the Jesus is Lord Movement.

Protests and support

“Building communities” is the social media magic once celebrated before “fake news” became a bigger buzzword. In the Philippines where the majority are Catholic, those who are queer won’t always find support from their immediate communities. Thanks to social media platforms, however, they are able to find like-minded people, communicate with strangers, and curate connections online, which is useful for those like Mikee who have come to terms with their queerness but not the consequences of coming out.

Young and immersed in pop culture, gay Twitter is filled with memes, celebrity gossip, and the occasional “thirst trap.” While they are spread across political spectrums, the skew toward liberal values is stark. It is often within these communities that support for human rights and the defense of democracy can be found.

Gay Twitter in the Philippines would come to the defense of basic rights that had been under fierce attacks under the previous Duterte administration.

When then-president Rodrigo Duterte and his allies moved to shut down media organizations in the Philippines, for example, LGBT-focused accounts were the quickest to protest online. This sector is also behind the biggest online protests on social media, such as the #OustDuterte campaign that happened at the onset of the pandemic.

They’re quick to come together in the face of discrimination, such as an incident last year in one of the country’s poshest business districts.

Transwoman Louis Marasigan recalled to us that while shopping at a store in Taguig City, in October of 2022, she was asked by a store clerk to use the male fitting room. Even after saying that she’s a woman and that she would be uncomfortable using the male fitting room, the store still barred her from the female fitting room. The clerk insisted that allowing her would make the other customers uneasy – even if she was the only customer waiting at the fitting room at the time. The store manager, who also happened to be gay, refused to help her.

In tears, Louis recounted the incident on TikTok where it quickly went viral, drawing widespread reactions from the queer community.

Within hours, her TikTok video was reposted on Twitter and retweeted thousands of times. At its peak, there were at least 25,000 tweets about the incident in a day.

The support spilled over to the physical world. People started to reach out to Louis to send her comfort food, while business owners invited her to their stores. Most important to her was the legal support she was offered by concerned groups and allies.

“The biggest help to me was the legal advice, as well as the support network I was introduced to by Ms. Mela Habijan,” she told us. Mela Habijan, crowned the first Miss Trans Global in 2020, is a staunch advocate of LGBTQIA+ rights.

The online furor prompted the store to reach out to Louis eventually. They’ve since apologized and clarified that they have gender-sensitive policies in place and were committed to retraining their staff about them.

But the trauma will likely remain, Louis said, recalling the volume of hate she received online. “I received more hate messages after it went viral…especially on Facebook. Some even threatened to kill me,” she said. After the incident, Louis said she was anxious to return to Taguig City for a while, fearing that the threats may actually turn real. “If only there was a law against discrimination, there would definitely have been a case against the store.”

Country of contradictions

Isolation and exclusion are nothing new to the LGBT community in the Philippines.

“For members of the LGBT community, we’ve gotten used to living in a society where we’re always isolated and excluded, so we’re almost always trying to find, search or create communities. That’s where social media has become particularly effective: connecting us to people with similar values,” said Reyna Valmores of the gay rights advocacy group Bahaghari.

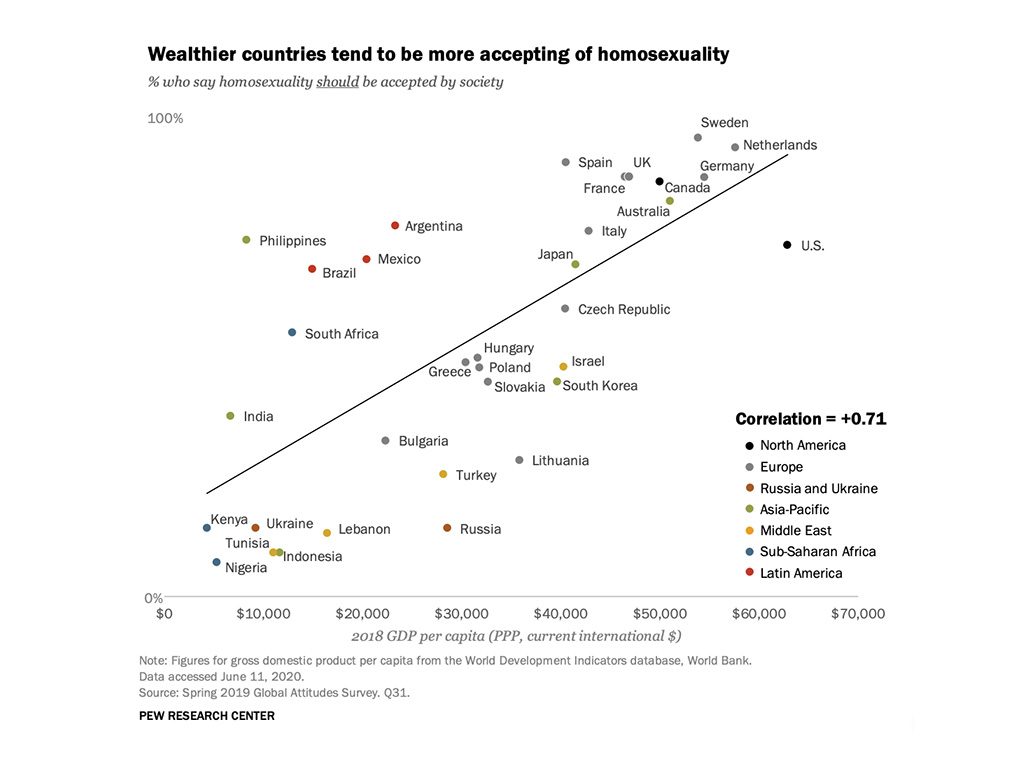

But surveys show otherwise, as some said that the Philippines is one of the most LGBT-friendly countries in Asia. A recent survey by the Pew Research Center showed that at least 73% of Filipinos think homosexuality should be accepted by society. This has been the same percentage since 2013, and the earliest conduct of the same survey in 2002 shows that acceptance was already at 64%.

The Philippines looks like an anomaly in Pew Research Center’s survey. Where data shows a high positive correlation between the country’s wealth and its acceptance of LGBT, the Philippines is almost as accepting of the queer community as its wealthier counterparts.

Other surveys tell a more complicated relationship between the LGBT community and the predominantly Catholic country. A Social Weather Stations (SWS) survey said that at least 60% of Filipinos know someone who is gay, but only 2 out of 10 Filipinos accept same-sex marriage.

The 2019 SWS survey added that 60% of Filipinos agree that the LGBT community experience discrimination and 55% are in favor of passing the law protecting their rights. But there are reservations with this support: 47% think transgenders shouldn’t be allowed in female restrooms and 48% do not agree that they should be allowed to change their official documents, such as birth certificates, according to their gender identity. This is on top of the continued discrimination LGBT persons face on the ground, which is documented in different reports.

This is why advocates like Reyna always emphasize that the Pride movement, as colorful and vibrant as it has become, is still a protest against the systemic discrimination of the LGBT community in the Philippines.

Over the years, they have leveraged the power of social media to spark collective action and challenge the status quo. Many organizations like Bahaghari, have relied on the supportive and social media-savvy queer community online to push the gay rights movement forward.

“Members of the community who also want to push for their rights, they know how effective social media can be,” Reyna told us, but with the caveat that activism on the ground is still important. “After all, not every Filipino has access to the internet.”

The SOGIE bill

At the center of the local gay rights movement is the campaign for a law that punishes discrimination on the basis of one’s sexual orientation, gender identity, or expression.

First filed in Congress in the year 2000, the bill is yet to be enacted into law, becoming the longest-running bill to be under Senate interpellation in the Philippines. Now sitting in the legislative body for 23 years, it’s surpassed even the controversial Reproductive Health Bill, which took 15 years to pass into law. (READ: TIMELINE: SOGIE equality in the Philippines)

The bill was first filed in 2000 by the late senator Miriam Defensor-Santiago and former Akbayan representative Loretta Rosales. Santiago’s bill focused on degenderizing the Labor Code and prohibiting employment discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, while Rosales pushed for an Anti-Discrimination Act that tapped into the Bill of Rights, seeking to prohibit broader areas of discrimination on the basis of SOGIE.

Facing stiff opposition each time they’re proposed, the bills were rejected, redrafted, and then refiled in every Congress since then.

Religious groups and politicians have made it a point to stop or delay the passage of any law that, in their view, promotes homosexuality and “immorality.” This includes bills on same-sex marriage and even reproductive health.

Advocates, on the other hand, would push for provisions each time the bills were refiled, covering other forms of SOGIE-based discrimination.

Now known as the Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Expression, and Sex Characteristics (SOGIESC) Equality bill, the current version filed in both the House of Representatives and the Senate is aiming for equal access of the LGBTQ+ to basic rights and services.

It proposes the prohibition of discriminatory acts if made on the basis of SOGIESC, including the denial of access to health and public services, refusing admission or expulsion in schools on the basis of SOGIESC, and revoking the accreditation of organizations based on the SOGIESC of members.

It also penalizes other forms of SOGIESC-based harassment, such as forced medical examinations, as well as conversion therapies. The recent versions also include indirect forms of discrimination like the exclusion of an individual from government aid on the basis of their SOGIESC.

One of the challenges, according to Reyna, is awareness.

”At the basic level, people don’t know what the SOGIE Bill is. Maybe among progressive circles, we do. But if you reach out to communities, they’re always asking, ‘Ano ba ‘yang SOGIE bill na ‘yan?’ (What is this SOGIE bill?) Even if they’re also gay.”

But gay rights groups all over the country have not stopped campaigning for the passage of SOGIESC both on the ground and online. The network graph below presents a snapshot of the tightly-knit gay rights community on Facebook. Each node presents a Facebook page or group that creates or shares content about the SOGIE Bill, and they are linked whenever they amplify or share each other’s content.

In 2018, conversations on SOGIE on social media were still driven by gay rights groups and queer communities. While there were a few faith-based groups posting against the bill, their presence was still insignificant and showed low networked behavior, at least compared to the pro-SOGIE communities.

“The biggest challenge has always been politicians who are dedicated and have made it their life’s work to stop any legislation for the LGBT community,” Reyna said. She singled out former senator Vicente Castelo Sotto III, who, during his term as Senate president, declared that the SOGIE bill had no chance of passing in the Senate.

Religious vote

Politicians like Sotto are not the exception but the norm in Congress, where lawmakers are held captive by the religious vote.

The Filipinos’ predominantly Catholic population gives churches so much influence during elections, and some Christian sects have leveraged this by openly endorsing candidates and offering voting blocs. Some church personalities have also been elected.

For example, the SOGIE Bill’s biggest opposition in the House of Representatives is Manila 6th District Representative Benny Abante, a pastor for the Metropolitan Bible Baptist Church. Abante, who is also chairperson of the House of Representatives committee on human rights, has been blocking the SOGIE bill since its first filing, saying that it would promote “morally reprehensible sexuality.”

He has made a brand for himself in advocating against the LGBT community: in 2009 he filed a bill criminalizing the conduct of same-sex marriage, and in November 2022, he filed House Bill 5717, which seeks to protect heterosexuals in expressing their views against homosexuality.

The pushback against any policy that goes against religious beliefs is just as strong outside the walls of Congress, where religious groups do not shy away from demonstrating the strength of their numbers. Thousands of religious Filipinos have marched on the streets to protest against the Reproductive Health Bill, which passed in 2012 after 15 years of push from advocates, with support from the late president Benigno Aquino III.

In opposing the SOGIE Bill in 2006, Abante also claimed to represent 35,000 churches all over the country that have come together to unite against the bill.

In the next part of this report, we’ll go through how the same platforms that empowered communities like that of Mikee’s can also empower those who want to silence them. And while social media has given the queer minority a voice, it didn’t take the conservative majority long to retake control of the online discourse, muddle the truth, and defend an oppressive status quo. – Rappler.com

(READ: Conclusion: Disinformation on SOGIE bill spreads as Filipino queers face real-world discrimination)

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center. Research was also made in collaboration with TheNerve, a Manila-based consultancy that specializes in analyzing data to bring forth powerful insights and narratives.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[DECODED] The Philippines and Brazil have a lot in common. Online toxicity is one.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/misogyny-tech-carousel-revised-decoded-july-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.