SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[In This Economy] PH poverty dropped in 2023. But it’s too damn slow.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/01/TL-poverty-jan-5-2024.jpg)

Let’s start off 2024 with a bit of good news.

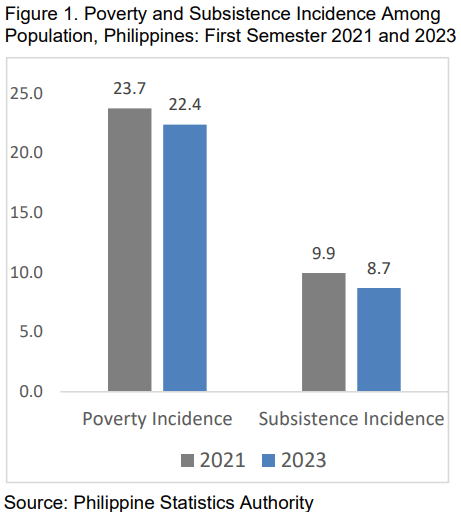

In the first half of 2023, the poverty rate (or the percentage of Filipino individuals living below the poverty line) went down to 22.4%, or a little above one-fifth of all Filipinos.

That’s lower than the 23.7% two years prior, in 2021 (see Figure 1). That also translates to nearly 900,000 fewer poor Filipinos over the same period.

Looks good, right? A closer inspection, though, will show that poverty is going down at a lamentably slow rate.

Figure 1.

Snail’s pace

When I first wrote for Rappler in 2013, more than a decade ago, the poverty rate for the first half of that year was nearly 25%. Almost 1 in 4 Filipinos was considered poor.

Sure, poverty has gone down since then. But a decade later, the poverty rate went down by just 2.6 percentage points. That’s equivalent to a poverty reduction rate of just 0.26 percentage points a year. Pitiful!

The slow decline of poverty was of course disrupted by the pandemic. In 2021, the number of poor people reached a peak of 26.1 million. But the number was likely larger in 2020 during the height of the pandemic. It just so happened that we don’t have a precise idea, because the government was not at all able to collect survey data during the lockdowns.

Now that the economy is recovering in earnest, it’s natural to see poverty go down as well. But the number of poor people in 2023, which numbered 25.24 million, was still higher than the 22.26 million poor in 2018 before the pandemic.

In short, there are still more poor Filipinos now than before the pandemic.

The rate of poverty reduction from 2021 to 2023 was also 0.65 percentage points per year. That’s 2.5 times faster than the average rate over the past decade.

But still, as you’ll see in a bit, it’s nowhere near the rate needed to meet the goals of the current Marcos administration.

Impossible dream

Remember the first State of the Nation Address of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.? He bombarded the Filipino people with tons of economic statistics in the first part of that speech.

One of those statistics is his target for poverty reduction. By 2028, he said, the poverty rate must be down to 9%. The first time, if ever, we’ll ever reach single-digit poverty rates.

That’s too ambitious, at the rate we’re going.

Note that 2028 is just five years away from 2023, when poverty was at 22.4%. To go down to 9% in five years, the rate of poverty reduction will need to be a whopping 2.68 percentage points per year!

To put that number in perspective, that’s more than four times the rate during the pandemic, and nearly 11 times the rate over the past decade.

How the hell will the Marcos administration reduce poverty that fast? I feel this is an impossible task, and the administration set itself for failure by aiming for such an impossible goal.

But why is poverty reduction so difficult in the Philippines? This problem has long troubled economists and policymakers, and it will take an entire semester (or more) at the UP School of Economics to discuss all the nuanced details.

One of the most basic stylized facts about Philippine development is that our economy grew quite fast in recent decades, but poverty reduction has not caught up. Put another way, fast growth is not translating to poverty reduction.

It’s quite embarrassing, really. Other countries, including ASEAN neighbors, have done a much better job than us. Heck, Vietnam is now richer than us, and Lao PDR is not far behind!

A knee-jerk if not lazy reaction is to blame chronic poverty on politics and politicians. To some extent that’s valid. But by no means is that the full story. Nor can we blame everything on lack of economic aid or ayuda (although that was certainly wanting especially during the draconian lockdowns).

Here are some known bottlenecks: very poor investments in human capital (education and health); overreliance on services and a lack of support for high-value added industries (including manufacturing); a perennial lack of investments due to red tape, uncertainty, and poor infrastructure; the lack of competition or a level playing field among businesses; poor governance, encompassing regulatory capture and lack of rule of law. Phew. What a list.

Despite all this, our economy continues to grow at a respectable rate. But while growth is necessary for poverty reduction (insofar as it creates more opportunities for more Filipinos), growth is by no means sufficient.

Achieving high growth while reducing poverty fast are not mutually inconsistent. We can pursue both, if politicians focus more on the issues and do what’s right. But given our state of affairs, that might be asking too much.

Self-reported poverty

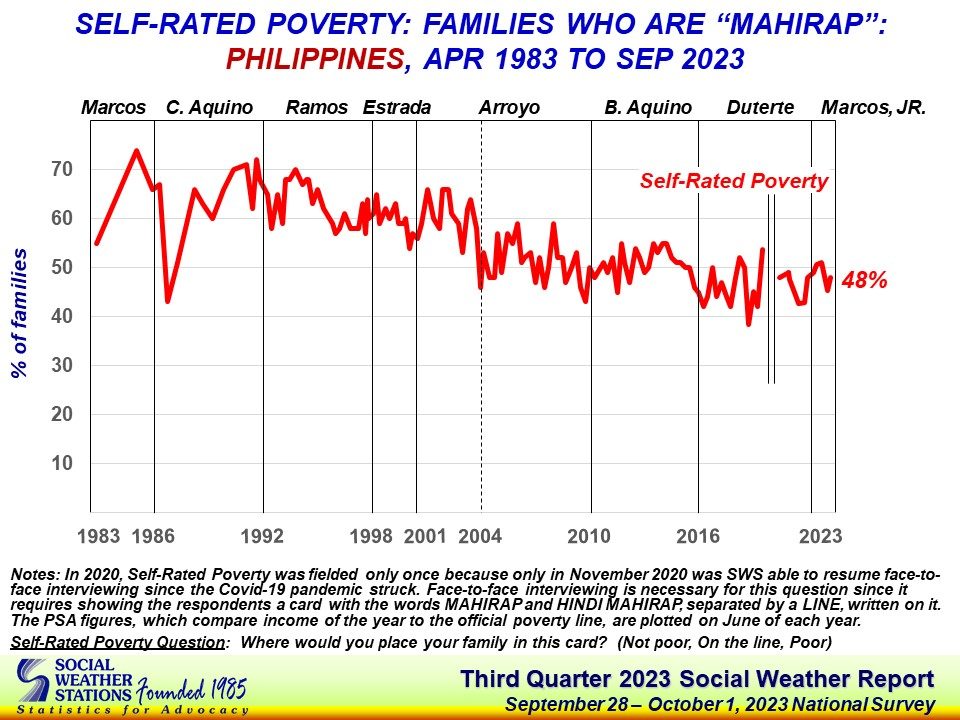

Finally, let’s look at another set of good data, coming from the Social Weather Stations (SWS), founded by economist Mahar Mangahas.

In November, SWS reported that 48% of Filipino families considered themselves “poor” in the third quarter of 2023. That’s almost half of all families, and higher than the 45% in June (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

That also translates to 13.2 million poor families: almost thrice the 4.5 million poor families reported by the government, and almost two million more than the poor Filipinos recorded by SWS two years prior.

If we focus on the first half of 2023, the SWS poverty rate was still 48%: higher than last year and just about the same as in 2021 (Figure 3).

In short, the SWS saw a stagnation of the poverty rate, over the same period that the government saw a statistically significant drop.

Figure 3.

Of course, self-rated poverty is a different creature compared to poverty as defined by the government (which is based on the minimum budget needed by a family of five to make ends meet in a month). We don’t have space here to explain all the nuanced differences.

But I would argue that self-reported poverty is just as informative as the official stats, and it may offer a valuable alternative lens for us to understand what’s really going on.

My sense is that self-rated poverty may be a better metric or barometer of the plight of the poor, especially during times of accelerating prices. Higher inflation reduces the purchasing power of households, and this can be more salient for Filipinos when asked to rate themselves whether they’re poor or not.

This year I hope to conduct more research on this, with the support and encouragement of Dr. Mangahas. Let’s see what the data will reveal. – Rappler.com

JC Punongbayan, PhD is an assistant professor at the UP School of Economics and the author of False Nostalgia: The Marcos “Golden Age” Myths and How to Debunk Them. JC’s views are independent of his affiliations. Follow him on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ Podcast.

2 comments

How does this make you feel?

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[EDITORIAL] Apat na taon na lang Ginoong Marcos, ‘di na puwede ang papetiks-petiks](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/animated-bongbong-marcos-2024-sona-day-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=280px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] Delulunomics: Kailan magiging upper-middle income country ang Pilipinas?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/in-this-economy-upper-middle-income-country.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=421px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Marcos Year 2: Hilong-talilong](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/animated-bongbong-marcos-2nd-sona-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=136px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Newspoint] A fighting presence](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-a-fighting-presence.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=441px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

I agree: “My sense is that self-rated poverty may be a better metric or barometer of the plight of the poor, especially during times of accelerating prices.” The PSA rating may have been manipulated for the Government to look good. Let us just hope that the SWS rating will not be manipulated, too. So, would President Marcos Jr. continue with his Impossible Dream?

The PSA data are credible and accurate, I have no doubt about it. It’s just that they’re measuring poverty differently than SWS. Rather than compare the levels of poverty between them, it’s more useful to compare trends/changes.