SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Literature is one of the many facets in which we store the nation’s collective memory. But what does it say when the state fixates on banning artistic works which are receptive to the country’s political situation?

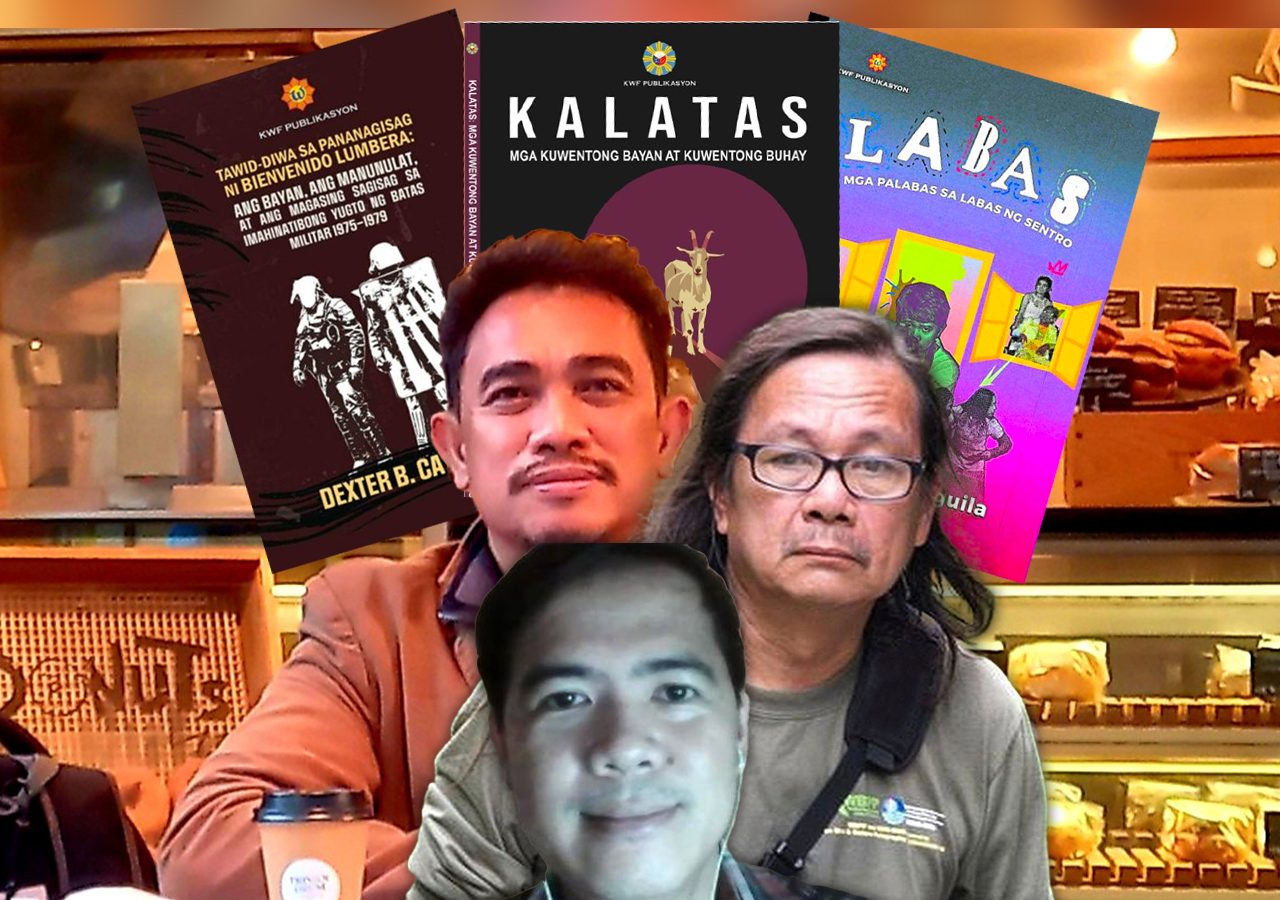

For Dexter Cayanes, Rommel Rodriguez, and Reuel Aguila, three of the five authors whose works were tagged as “subversive” and “anti-government,” banning literary forms that articulate the truth is an “attack” on our nation’s memory.

“Kung cinecensor ka ng estado, takot sila sa katotohanan batay sa sining (If the state is censoring you, they are fearful of the truth based on art),” Rodriguez told Rappler.

Last August 9, the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino (KWF) released a memorandum ceasing the publication and distribution of works with “subversive” and “anti-government” ideologies. Also included in the order were books by Malou Jacob and Don Pagusara.

This came as critical voices continue to be undermined under the Marcos administration such as the red-tagging of activists, intimidation of independent media, and the gruesome deaths of journalists.

More than a month after KWF released the order, some commissioners who initially signed the document withdrew their signatures, nullifying the ban.

Cayanes said his work, Tawid-diwa sa Pananagisag ni Bienvenido Lumbera: Ang Bayan, ang Manunulat, at ang Magasing Sagisag sa Imahinatibong Yugto ng Batas Militar 1975-1979, sought “to understand the importance of freedom to writers.”

Rodriguez’s Kalatas: Mga Kuwentong Bayan at Kuwentong Buhay, meanwhile, is a historical and contemporary collection of short fiction and essays banned after mentioning the words “sandata” and “rebolusyon.”

Aguila’s Labas: Mga Palabas sa Labas ng Sentro is a compilation of three plays: a satire on noontime shows, a prisoner’s homecoming, and a story of a news photographer who covered martial law.

Demystifying the myth

One common theme of the works of the authors is emphasizing the country’s political climate based on historical facts and significant events.

“Kami na nasa sining, ang layunin namin lumikha ng sining at magsabi ng katotohanan (For those of us in the arts, our purpose is to create art and tell the truth),” Rodriguez explained.

By adding elements about martial law, the works of leftist scholars, and narrating themes of oppression in the country, the authors drew the ire of government officials.

Rodriguez said that when a government agency uses its power to designate who is subversive or not without a reasonable basis, it tells more on them fearing the truth.

“It’s a [form of] mythmaking. Nililikha lang kami bilang enemy of the state [bilang] mga ‘subversives’ (We are fabricated to be enemies of the state as ‘subversives’).”

The authors also noted that antagonizing those who simply speak the truth manifests “state paranoia” or the seeming fabrication of the identities of critical and progressive writers.

“Paano magiging subversive ‘yung isang libro or sabihin na nating anti-gobyerno na nagsasabi ng totoo? Yung rason ng pagkakasulat o pagsasagawa ng pananaliksik ay nasa punto de bista ng paglalahad ng katotohanan noong mga panahong iyon,” Cayanes said.

(How can a book be subversive or anti-government when it is simply narrating the truth? The intent behind the writing or conduct of research is from the point of view of elaborating facts during such time.)

Parallels to the past

Aguila recounted how the now-voided ban reminded him of a similar experience during the martial law imposed by Ferdinand Marcos, Sr. in the 1970s. After finalizing the script of Sakada, a 1976 film directed by Behn Cervantes about the plight of sugarcane farmers in Negros, he was blacklisted from the movie industry.

“No one wanted to get us [in films] and we were invited by the military for questioning,” he shared in a mix of English and Filipino.

During the martial law period, the state control of media and publication led to a rich underground literature that criticized the government’s abuse of authority.

With the Marcos family back in power, the authors believe that the present is drawing significant parallels to the past.

Aguila added that the government is using two measures to revise history – to demonize writers like the five authors included in the KWF order and to look for writers who can sanitize their names.

“Ang major concern nila, maghanap ng author na papabor sa kanila, ‘yung magrerevise ng history (Their major concern is to look for writers who can favor them, who can revise history).”

The Marcos family has capitalized on trolls, vloggers, and even artists to beautify their name and sugarcoat the horrors of martial law.

Even institutions like the NTF-ELCAC and SMNI have become channels for red-tagging activists, artists, and individuals who criticize the Marcos administration. Recently, the Department of Education trended online for its alleged rebranding of martial law to “new society.”

Cayanes said that distorting parts of Philippine history leads to a gap in our collective consciousness as a country. Cayanes called this a form of anti-intellectualism.

“It is against achieving full literacy through critical thinking and research as the basis of transformational knowledge and empowerment of our people,” he said.

The authors also believe that the disappearances and deaths of those expressing opposition throughout Philippine history may have pushed writers into hiding, yet it has never hindered them from voicing their opinion.

“Kahit si Dr. Rizal noong 1896, kaya nga siya napaslang sa Luneta,” Cayanes said. “Inakusahan rin siya ng subversion ng Spanish government.”

(Even Rizal in 1896, the reason why he was murdered in Luneta. He was accused of subversion by the Spanish government.)

“Hindi iyong books namin ang unang nacensor. Nangyari na ‘yan sa mga bansang merong history of revolution and rebellion,” Rodriguez added

(Our country is not the first in having our books censored. This has already happened in countries with histories of revolution and rebellion.)

Supporting the ‘freedom to write’

As the Philippines celebrated its 88th National Book Week on November 24 to 30, Aguila laments the seeming disparity between the government’s efforts to promote reading and its endeavors to identify certain types of books as anti-government.

He added that apart from improving the state of publishing in the country, one form of support that the government can extend is the freedom to write.

“Anong support ng nagdeclare, sa kasong ito ang government, ang pwedeng ibigay para sa development ng book publishing? Meron siyempre financial [support] at iyong kabilang swing ng pendulum, freedom, walang censorship,” Aguila said

(What form of support can the government provide to the development of book publishing? Of course, we have financial [support], and on the other swing of the pendulum, freedom, no censorship.)

The three authors also believe that by developing local literature and readership, the public is immersed in diverse political and cultural standpoints that mold the history of the Philippines.

“Ang layunin ng panitikan huwag kalimutan ang alaala (The purpose of literature is to not forget our memories),” Rodriguez shared.

“Kapag nagbasa tayo, nakakatulong ito para maangkin natin ang nation’s memory, our country’s narrative using literature para mas magkaroon tayo ng pag-unawa sa ating sarili, sa ating bayan, at sa ating pagka-Filipino,” Aguila added.

(When we read, it helps in reclaiming our nation’s memory, and our country’s narrative using literature to have a deeper understanding of ourselves, our nation, and our being as Filipinos.)

Despite the intimidation brought by the voided memorandum, Cayanes, Rodriguez, and Aguila agreed that the fight for freedom of expression continues.

“Kasaysayan at kasaysayan ang magpapaalala sa atin na hindi naman talaga mapipigilan ng simpleng pagtatakda o pagmamarkang ‘subersibo’ [at] ‘anti-gobyerno’ sa isang panitikan para tumigil ang mga manunulat,” Cayanes added.

(History reminds us that the act of marking literature as ‘subversive’ and ‘anti-government’ will never hinder writers.) – Rappler.com

Farley Bermeo Jr. is a communication arts graduate from UP Los Baños and a Digital Communications volunteer at Rappler.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.