SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

LONDON, United Kingdom – The ways the Philippine government has repressed the media are part of a global trend on attacks on press freedom, legal experts said during the 2022 Reuters Trust Conference held in London on Wednesday, October 26.

Former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte followed a model of autocrats around the world who use complex and confusing foreign ownership and tax laws to attack the independent press, said Can Yeginsu, deputy chair of the high-level panel of legal experts on media freedom.

The closure orders on Rappler, the biggest television network ABS-CBN, and the threats against broadsheet Philippine Daily Inquirer, which almost led its owners to sell to a Duterte campaign donor, all hinged on supposed foreign ownership and tax violations.

“You get a sense of the way in which the law is being used for collateral purpose to put a pressure on independent journalism in a place such as the Philippines. The reason, I think, states are pursuing this strategy is because investigations around tax, foreign ownership, foreign agent laws – these are complex areas, they turn on the application of overbroad laws,” said Yeginsu.

“But they are there to obfuscate, raise suspicion, cast doubt on the integrity of the individuals being targeted. And I think it’s a relatively new state strategy that we are witnessing,” he added.

In September, a Russian court shut down newspaper Novaya Gazeta, one of the last independent media outlets in Russia, after it was accused of violating a restriction on foreign agents. Its critical coverage of the Russian invasion of Ukraine drew the latest blow on the three-decade old newspaper, led by Dmitry Muratov who won the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize with Rappler CEO Maria Ressa.

“Move away from Maria Ressa and across Dmitry and the way in which the foreign agent laws in Russia were promulgated and used against human rights defenders, and then extend it and use against media outlets culminating in the recent closure of Novaya Gazeta – courts are now having to grapple with the collateral uses of regulatory chill on journalists,” said Yeginsu.

Yeginsu also observed the pattern by which governments enacted “vague laws” during the pandemic, supposedly to crack down on disinformation.

“Some of the new legislations were very hastily enacted during the pandemic. From a policy perspective, you can understand why a government may want to regulate the spread of false information if it relates to public health concerns about false news around vaccines,” he said.

“The problem of course is that it has led dozens of countries now to use that as a pretext to enact very vaguely worded, overbroad legislation where the fear is that legislation is going to be deployed for collateral purposes,” Yeginsu added.

The Duterte government enforced the feared anti-terror law at the height of the pandemic in 2021, a law slammed across political aisles in the Philippines as a pretense to crack down on dissenters. It became one of the most legally challenged laws in Philippine history, but the Supreme Court had recently upheld its constitutionality, pending actual cases.

One of the last few actions of the Duterte government, aside from affirming the closure order on Rappler, was blocking the alternative news website Bulatlat on browsers for its alleged link to communist groups. The basis of the National Security Council memorandum was the anti-terror law. Bulatlat had just won an injunction against the order.

Even the harsher penalties for libel under the Philippines’ Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 – under which Ressa has been convicted which she has appealed – exists in other countries such as Bangladesh where, according to Irene Khan, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of expression, “the digital security act has much higher punishment on online media than traditional legacy media.”

What would Marcos do?

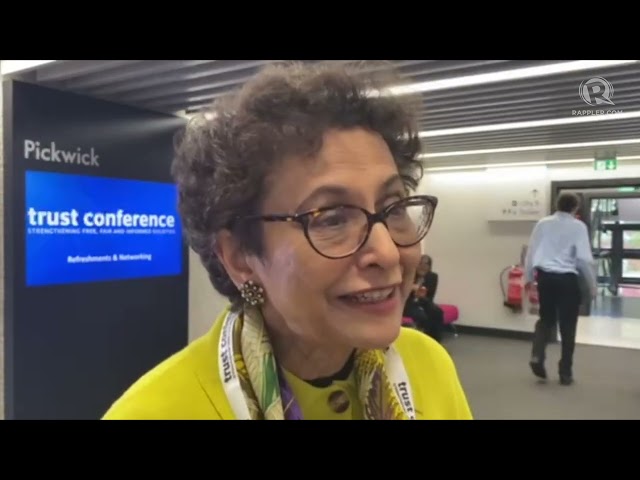

Khan told Rappler on the sidelines of the conference that “it’s very sad to see the denigration of media in the Philippines.”

Khan said the Duterte government had invited her before, but she had yet to make the trip. She hoped that the government invitation would still be valid under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., son and namesake of the late Philippine dictator who shut down media companies during Martial Law.

“I don’t want to prejudge the [Marcos] administration, it’s been in place for a few months but what I would hope to see are big changes. Big reform in policy, you have a constitutional protection that is not being exercised properly. The government is a party to international conventions which uphold free, independent media, and I would like to see the government live up to these obligations,” said Khan.

Under Marcos government, red-tagging against journalists or the vicious linking of media personalities to communist rebels has not ceased. Bulatlat managing editor Len Olea was the latest target of red-tagging that was done on the airwaves of SMNI, a channel that campaigned for Marcos in the election, and owned by doomsday preacher Apollo Quiboloy, wanted in the US for sexual trafficking of children.

Continued attacks

Khan said that attacks on women journalists have also become more prevalent across the world.

“There are well-coordinated attacks online, basically in order to wear them out, to attack and create so much mental distress on the individual. The risk is many of these online attacks translate into offline action,” said Khan.

The killing of hard-hitting broadcaster Percy “Lapid” Mabasa has also created stir in the Marcos government because Mabasa had been vocal against red-tagging and Marcos himself.

There are no clear motives established yet for their killings, but Khan noted that the government has an obligation to solve the murders regardless of whether they had some degree of involvement.

The Philippines is 7th in the world in terms of most number of unsolved journalist killings, according to the 2021 Global Impunity Index of the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

“We should not forget that 9 out of 10 cases of killings of journalists are not investigated and not prosecuted. If the states are not willing to investigate killings of journalists, if that’s the situation, then how can states protect journalists?” said Khan.

“Whether it’s the prosecution, the judiciary or the parliament, there seems to be a devaluation of media freedom,” Khan added. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.