SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Following the uncoordinated, unannounced visits of police to several journalists in a bid to secure them, anxiety was felt across the media sector and its advocates.

Some social media users questioned this reaction and even commented on reports that journalists should welcome the visits. But where did the uneasiness come from?

According to rights group In Defense of Human Rights and Dignity Movement (iDEFEND) and Albay 1st District Representative Edcel Lagman, the visits were reminiscent of “Oplan Tokhang.”

Another human rights group, Karapatan, said that these actions encroached civilians’ right to privacy.

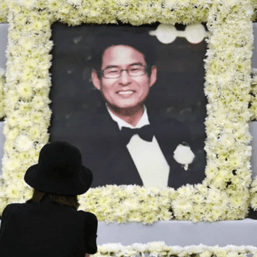

Since the killing of broadcast journalist Percy Lapid on October 3, police have been conducting house-to-house visits to some journalists with the “good intention” of protecting journalists within their areas of responsibility.

The media has tracked at least three journalists who were subjected to police visits, including GMA reporter JP Soriano, ABS-CBN reporter Adrian Ayalin, and DWIZ/IZTV anchor David Oro.

Lagman said the home visits were similar to “Oplan Tokhang,” the operation popularized during former president Rodrigo Duterte’s drug war, when police knocked on the doors of suspected drug personalities. Many were killed in these operations.

“Crusading journalists need police protection from threats and harm, not police intrusion into their privacy. The recent unannounced visits of police officers, mostly in plainclothes, to the homes and studios of selected broadcasters is reminiscent of the intrusive and illicit ‘Operation Tokhang’ on drug suspects,” Lagman said in a statement on Monday, October 17.

“These veiled harassments must be stopped as they constitute attempts at prior restraint on the freedom of expression,” Lagman added.

Rose Trajano, international advocacy officer of iDEFEND, shared this view.

“The visits that the police conduct at the homes of journalists or vulnerable persons or potential victims of human rights violations, is reminiscent of ‘Tokhang’ operations during the Duterte administration, which often resulted in EJKs (extrajudicial killings) right in the victim’s homes and witnessed by their families, neighbors,” said Trajano.

Trajano said that “deeply entrenched impunity” has caused many of the cases to remain unsolved, with few held accountable, except in the case of murdered student Kian delos Santos.

“The criminal justice system never provided credible response to assure the public that they are protected by the law against human rights violations by law enforcers themselves, so the public is highly critical of home visits,” said Trajano.

In a statement on Tuesday, October 18, Karapatan Secretary-General Cristina Palabay also slammed the visits to journalists’ homes as a “blatant invasion of privacy” and “ill-disguised threat and harassment.”

Police visit to abused student

This is not the first time police have knocked on doors with the intention of helping the person they were visiting.

Enough is Enough (EIE), a group of convened students who have survived sexual harassment in schools, told Rappler that on September 2, two uniformed police officers visited the residence of one of the victim-survivors of sexual abuse at Bacoor National High School.

Victim-survivor Robert, not his real name, said that the police wanted him to come out of the house and allow them to interview him. (READ: ‘He called us baby, and made us watch gay porn videos’)

“Takot pamilya ko (My family was scared),” the EIE quoted Robert as saying.

The group said that the police waited for Robert outside his house for almost two hours. Robert’s family asked the assistance of their neighbor, a close relative, to talk to the police instead.

The police eventually left but gave Robert and the family the contact information of one officer, Police Corporal Investigator Lea Cahinhinan.

EIE lead convenor Sophia Reyes said that sending uniformed police officers to the survivors’ homes without prior notice “would undoubtedly cause unwarranted fear among the victim-survivors and their families.”

Reyes added that police visits may also contribute to social stigma, as the visits may intrigue neighbors who may not know about the trauma the survivor experienced.

“This could mean haphazardly exposing the identity of the victim-survivor. The victim-survivor could receive unwarranted judgment from neighbors and passersby,” she added.

In the visits to journalists, some cops showed up uniformed like in the case of Robert, while others were in plainclothes, like the visit to GMA reporter Soriano.

National Capital Region Police Office spokesperson Lieutenant Colonel Dexter Versola told Teleradyo that some do not come in uniforms precisely to avoid the judgment of neighbors.

“Minabuti na mag-civilian para hindi po malaman, o ‘yung cover nga po ng media, baka gusto niya ay discreet lang po ang pagbisita (Civilian clothes were the better choice so that the media’s cover wouldn’t be blown – perhaps they wanted a discreet visit),” Versola said.

Rappler sought Cahinhinan’s comment on whether they have changed their approach on protecting the abused students. Cahinhinan has yet to respond as of posting.

Appropriate avenues

The National Union of Journalists in the Philippines (NUJP) earlier said that the police visits were a violation of journalists’ right to privacy, and that these may trigger anxiety.

“Assuming good faith, these meetings and dialogues are best done through newsrooms or through the various press corps, press clubs, and journalists’ organizations in the capital,” the NUJP said.

Meanwhile, the EIE said that police should not demand and pressure victim-survivors to come forward.

“Victim-survivors should only come out when they are ready and on their own terms. These cases should be handled sensitively and tactfully,” said Reyes.

According to Karapatan’s Palabay, the police home visits have caused more insecurity among civilians.

“More and more, people are being threatened, coerced, and intimidated by abusive state forces and no longer feel secure in their persons and their own homes. We demand that state forces put a stop to their overarching arrogance, and desist from abusing their authority, encroaching on people’s privacy, and trampling on the rights of civilians,” said Palabay.

Since the Duterte administration, critical journalists have been vilified, harassed, and killed, just as in the case of Percy Lapid. Various sectors have condemned the attacks as detrimental to Philippine democracy. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] You don’t always need a journalism degree to be a journalist](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/jed-harme-fellowship-essay-june-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=287px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] Sexual harassment by the boss](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/sexual-harassment-by-the-boss-02292024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.