SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Kian delos Santos and Marion Navarro were born eight months apart and both came of age in Caloocan City. One would later be killed, and the other would go on to count the dead.

They were both 17 years old when Kian was mercilessly killed by police in the city that was often referred to as a killing field under Rodrigo Duterte. It was August 2017, a little over a year since the former mayor was sworn into the presidency, and more than 3,000 people were already killed by stage agents in the name of the war on drugs.

The deadly police operations were everyday reality for Navarro. She’d walk out of the house and hear news of a neighbor killed even before reaching the corner. Fear and violence were palpable in the air, translating into dead bodies, and witnessed by Navarro through the years.

Kian’s death triggered a massive uproar from the public, but it did not stop the killings. Navarro went to study behavioral sciences at the University of the Philippines while people in her community kept dropping dead either in front of their families, or their bodies dumped in roads or creeks for everyone to see.

“May time na sasabihin sa klase namin na kailangan makipag-usap sa mga pamilya ng mga namatay na parang immersion, pero iniisip ko noong panahon na iyon ay paanong immersion, eh doon ako nakatira?” she told Rappler in an interview.

(There were times we’re told in class to talk to families of those killed, like an immersion, but then I thought to myself: Is it even immersion when I live there?)

Navarro realized that she needed to do something. Barely into adulthood, she started doing research on the drug war at the Ateneo de Manila University’s Institute of Philippine Culture.

At 23 years old, Navarro now works as a junior research associate at the University of the Philippines Diliman’s Third World Studies Center (UP TWSC). Her tasks include helping out with the Dahas Project, an initiative that sought to initially document the violence that marked the Duterte years but has since also focused on the continued impunity under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

“Bata pa lang ako, nagbibilang na ako ng mga patay,” Navarro said. “Contribution ko na rin siya kasi ayoko na nalungkot lang ako o natakot, gusto ko na as much as possible, magkaroon ng meaning ang ginagawa ko.”

(I was already counting the dead when I was young. I see this as my contribution, that I do something meaningful with my fear and sadness.)

As of October 15, the Dahas Project has monitored at least 438 drug-related killings in the Philippines since Marcos became president, with 195 killed by state agents. The team noted that there were more killed in Marcos’ first year than Duterte’s last year in office. At least 342 between July 2022 and June 2023 against Duterte’s 302.

Counting the dead

Tucked inside one of the oldest buildings of the sprawling UP Diliman campus is a room scattered with shelves overflowing with books. A fat cat sleeps soundly near reference materials about prospects of peace in Mindanao and the country’s complicated history. A calendar featuring all Philippine presidents, a freebie from a local drugstore, greets you as you enter the room. Beneath it is a caricature of Duterte with his hand on his chin, a signature pose.

This is the home of UP’s Third World Studies Center, an institution established in 1977 in response to the repression of academic freedom by the Marcos dictatorship. It has produced both important academic papers and scathing statements on issues that hound the country, staying true to its activist beginnings but acknowledging its place in academe.

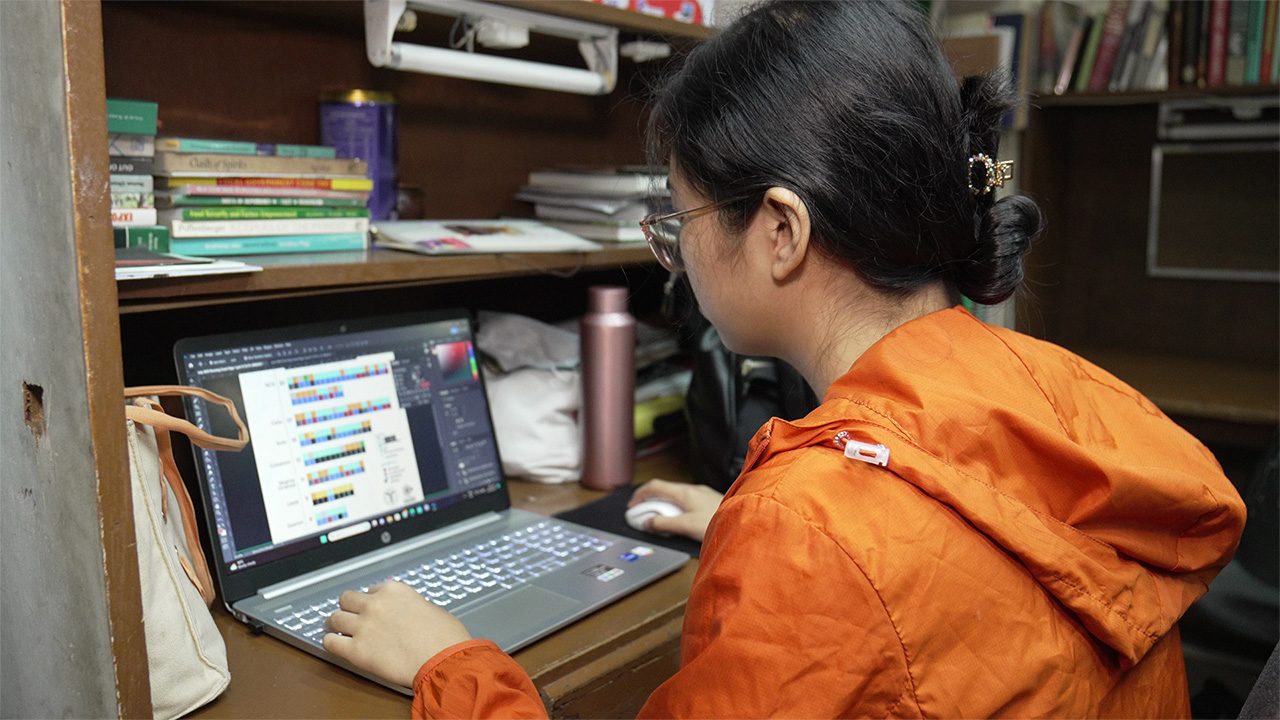

At any given time, one can see no more than three to four people hunched in front of their laptops, busy with their respective tasks. These are researchers like Marion Navarro, who scour the internet for media stories on people killed in drug-related incidents across the Philippines.

The products of long hours of research are what constitute the drug war tally of the Dahas Project. It is, by far, the only remaining effort to document the drug-related killings from Duterte to the second Marcos presidency, which has been marked by lack of transparency as the chief executive sought to present a “bloodless” anti-illegal drug campaign.

A May 2023 report by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights cited the Dahas Project as an example of “bringing casualty recording to bear on further compliance with international human rights and humanitarian law.”

The Dahas Project came from an ever bigger project between the state university and Ghent University in Belgium on violence, human rights, and democracy in the Philippines. But the idea of the drug war tally was borne out of the lockdowns caused by the coronavirus pandemic, according to UP TWSC university researcher Joel Ariate Jr. The researchers, all stuck in their homes, needed to think of a way to keep the discussion alive and push the project forward.

“It was a tedious process, ‘yan ang unang-una naming natutunan, na hindi lang basta-basta na gagawa kayo, bilangin ‘nyo, ilagay ‘nyo sa Excel sheet,” he told Rappler. “Para siyang isang circuit, algorithm, iyong ide-device ‘nyo kung paano ipo-proseso ang datos at ang datos ay in fragments.”

(First thing that we realized is that it’s a tedious process. It’s not so simple that you count the dead and put it in an Excel sheet. It’s like a circuit, there’s an algorithm, and you have to device how to process the data, and these data are in fragments.)

During that initial run, the team was able to find out that drug war killings continued even as the pandemic raged on. But this reality was largely ignored due to the health emergency. Still, the Dahas Project persevered, counting each dead while firming up its methodology and criteria.

Local media, who often cite police reports and blotters, prove to be vital in the methodology of the Dahas Project. Researchers scour the internet for media reports on drug-related killings, collect information on the deaths, and input them as data points into a database.

But what is a drug-related incident? For Dahas, it is drug-related if “a victim was killed through violent means” and meets one of the following conditions:

- Killed in a drug-related operation, activity, or encounter

- Reported to be involved in the drug trade or the anti-illegal drug campaign

- Reported to be in possession of illegal drugs at the time of death or when the body was found

- Reported to be linked to someone connected to the drug trade

- Killed by someone reportedly involved in the drug war for drug-related reasons or influenced by drugs

The Dahas Project usually releases weekly tally updates on social media, an effort to counter the constant discourse that Marcos’ anti-illegal drug campaign is blood-free.

Dealing with trauma

Each day feels the same but different for Dahas Project researchers. They sign in, scan the internet, log in the details, and discuss – sometimes debate – about the various nuances that come with their work.

But at the core of what they’re doing, one that took time for them to acknowledge, is the trauma that inevitably jumps from the gory details they uncover to their consciousness.

Nixcharl Noriega, who worked for the Dahas Project as research associate until late September 2023, spent a bulk of his time trying to get as much information about a drug-related killing. Most of the time he’d come across “very gruesome narration” of how killings were carried out, often with accompanying photos or even videos.

These details followed Noriega everywhere. He’d walk outside and immediately think a motorcycle-riding man is out to kill him. That the driver would pull out a gun and shoot him point blank, and end up like the thousands of other Filipinos in poorest communities.

“Nakakapanghina talaga ng loob…ang kailangan ko lang talaga na gawin ay lumayo nang kaunti at tumingin sa ibang bagay at huminga,” Noriega told Rappler. “Kasi kapag babad ka talaga sa mga ganoong klaseng balita, lumiliit realidad mo.”

(It’s really disheartening. What I do is I distance myself a bit, look at other things, and breathe. If you’re immersed in this kind of news, you tend to shut yourself away from reality and the world.)

The trauma also manifests itself through the gallow humor the team lets out from time to time, although they’re mindful that these are “bad jokes.” There is also the risk of being numb to the violence that pushes one to just aimlessly scroll through photos of dead bodies and not feel anything, until the impact manifests in some other ways.

“Sa vicarious trauma, it’s very hard to detect at inalert na lang kami ng mga ilan naming kasama na posible itong mangyari,” Ariate said. “Hindi agad-agad, pero nandiyan na, iyong zest for life mo wala na.”

(Vicarious trauma is very hard to detect, and we’re just alerted by other people that it could happen. Not immediately, but it’s there, you’d notice your zest for life is gone.)

But while the team deals with the trauma, they are also fueled by how important their work is, considering that the Dahas Project is the only remaining drug war tally in the Philippines. That, according to Ariate, “overpowers whatever physical and psychological malaise” they are feeling.

“Kumbaga sa giyera, ikaw na lang iyong tumatakbo, and it’s a killing field so sa mind mo ay sana ‘wag akong matapilok o sana huwag ako mabaril sa ulo, at iyan ang mentalidad sa ngayon,” he said.

“Kung ikaw na lang ang nag-iisa, matatawa ka na lang, wala ka na rin choice, ikaw na lang ang nandiyan eh, so a bit of humor na out of sheer persistence na gawin ito,” he added.

(In the context of a war, you’re the only one running and it’s a killing field so your mind is focused on hoping you don’t trip or get shot in the head. That’s our mentality now. If you’re the only one left, you’ll just laugh sometimes because you really have no choice anymore. So a bit of humor that we’re doing this out of sheer persistence.)

There is also the risk of becoming numb, as it often happens to people dealing with violence and trauma. For Noriega, the best way to counter this is to remember that at the center of their work are humans whose lives were unfairly cut short.

“Itong trabaho namin ay pagkilala na iyong mga napapatay ay tao rin…gusto namin kilalanin ang pagkatao niya sa pamamagitan ng pagkolekta ng impormasyon tungkol sa kanya at, pagpangalan sa kanya, iyan ang pinaka-importante,” he said.

(Our work is really to acknowledge that the numbers we are counting are people. We want to recognize their humanity by collecting information about them, to name them, that’s the most important thing.)

‘Permanent record’

Rodrigo Duterte left Malacañang with a bloody trail. Government data shows that at least 6,252 individuals were killed in police anti-illegal drug operations alone as of May 2022. This number does not include those killed vigilante-style, which human rights groups estimate to be between 27,000 and 30,000.

Advocates and other stakeholders waited with bated breath if the dictator’s son would be different. More than a year into his presidency, Marcos has distanced himself from the violence that marked his predecessor. In his second State of the Nation Address (SONA) in July, he said that “the campaign against illegal drugs continues, but it has taken on a new face.”

But the data does not lie, at least based on monitoring by the Dahas Project.

“Iyong departures sa demeanor, hindi nangangahulugan na departure sa policy [kasi] lahat ng patakaran sa tokhang, nandiyan pa rin, iyong mga nagpatupad, nandiyan pa rin,” Ariate said.

(The departures in his demeanor do not mean a departure from policy because all those who implemented tokhang are still there.)

There are days when there would only be two killings, or sometimes one. These are far and few in between, according to Ariate. They are not optimistic that there would be a big drop in the killings under the second Marcos presidency even.

“Hindi naman napapanagot ang mga dating pumatay, so walang sense of justice, walang sense of punishment,” Ariate said. “Anong pipigil doon sa mga pumatay na at pumapatay pa rin?”

(We’re not that optimistic because no one is being held accountable for those killed before. There’s no sense of justice, no sense of punishment. What will stop those who killed and who continue to kill?)

The killings under Duterte’s drug war are currently under investigation at the International Criminal Court. In the Philippines, however, only a few have been convicted in these killings. Duterte is yet to face any semblance of accountability.

The dream of the Dahas Project is to be rendered obsolete in the future. Not due to political repression, but because there is no more state-sanctioned violence, especially in the poorest communities. The team members pine for days where their internet sleuthing would no longer yield deaths, but they acknowledge that the dream is far-fetched, at least for now.

In the meantime, they hope to replicate the drug war tally in various communities, including schools across the Philippines, so there would be monitoring of violence at the microlevel.

But ultimately, the researchers want the Dahas Project to stand the test of time and serve as a reminder of the nationwide bloodshed that Duterte unleashed from the presidential pulpit and which continues under Marcos.

“Ayaw namin mangyari na 50 years from now, ang mga scholars na titingin sa panahon ni Duterte at sa panahon ni Marcos, eh magogoyo ng propagandista o mga apo ng dalawang ito, at sasabihing ‘“anong drug-related killings?”

“Gusto namin ito maging resilient, na maging permanent record talaga,” he said.

(We don’t want that in the future, scholars studying the time of Marcos and Duterte will be fooled by propagandists or granchildren of these two who will claim that there were no drug-related killings. We want to be resilient. We want this to be a permanent record.) – Rappler.com

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] A Duterte and Bato cop named Patay](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/tl-lito-patay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=322px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

The Dahas Project team deserves deep appreciation for their efforts. I hope their report will be accessible to the public.