SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

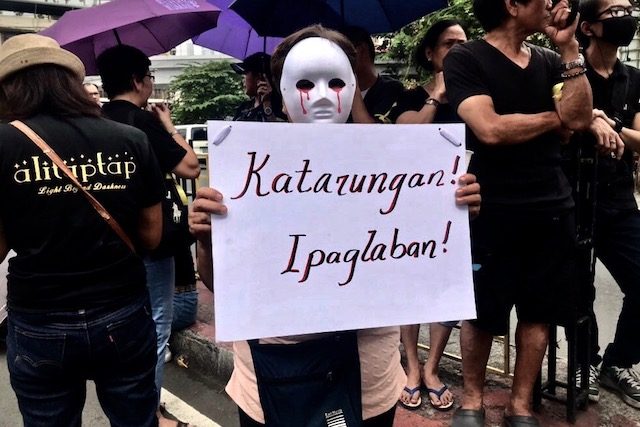

Editor’s Note: There is no denying that families left behind by victims of Rodrigo Duterte’s violent war on drugs want justice. In June 2021, then-justice secretary and now Solicitor General Menardo Guevarra said it would be difficult to file cases unless families and witnesses come forward. But in the context of the climate of impunity in the Philippines, pursuing legal cases at the local level means exposing themselves to harassment – or worse, death – especially in cases of anti-illegal drug operations where killers of their loved ones are part of their own communities. In this series, Rappler revisits some families who have chosen not to rely on domestic mechanisms and instead pin their hopes on the International Criminal Court.

Last of 3 parts

PART 1 | Drug war widow rejects police probe: My husband’s killer is one of their own

PART 2 | Kin of drug war victim: Can we even fight the police?

MANILA, Philippines – To understand the dynamics of Philippine communities, one has to remember how neighborhoods are laid out.

In Metro Manila, home to 13.4 million people or 12.37% of the entire Philippine population, families squeeze into what little space they can find. In the poorest communities, houses made of flimsy materials stand side-by-side with barely a gap in between. Small roads serve as shared spaces, often a playground for the neighborhood children or venues for birthdays, fiestas, or even wakes. Alleys are so narrow that one could just stretch an arm out to reach a neighbor’s door across from one’s own.

News is hardly ever left contained within homes. Stories spread so fast that a familial issue can become the whole neighborhood’s business in a span of hours. These take various forms – from pregnancy rumors to even the pettiest of all quarrels.

But in Rodrigo Duterte’s Philippines, mundane stories have been replaced by recollections of violence. The war on drugs, which killed thousands in its wake, forced people to be witnesses to their neighbor’s demise, to the upending of lives.

It takes Melanie* approximately five steps to reach the house of her nephew Billy, with both their homes also close to other family members’. This made get-togethers – if not the occasional catching up – easy to organize, if one is not too busy working.

One night in October 2016 changed everything. At 10 in the evening, at least eight gun-wielding men reportedly forced their way into Billy’s home, kicking the door out of the way. They first killed Billy with three gunshots in the head, before unloading the same number of bullets into his wife.

While the men were mercilessly killing her nephew, Melanie and her family were cowering inside their own home, fully aware of the unfolding violence but unable to do anything.

“Dikit-dikit lang ang bahay namin kaya lahat ng nangyari, lahat ng sigaw at putok, narinig namin,” Melanie narrated to Rappler. “Hindi ko malilimutan iyon.”

(I will never forget what happened that night. Our houses are just close to each other so we hear everything – the yells and the gunshots.)

A few moments of silence signaled that it was safe to go out. Melanie was met outside by police, members of Scene of Crime Operations (SOCO), and even representatives of a local funeral parlor – a usual sight following killings in Duterte’s war on drugs.

Melanie was not surprised anymore. Even if she was told that her nephew’s killers were wearing civilian clothes, she knew it was the police who were behind the gruesome act. It has happened so many times in their own neighborhood, she said.

By the end of September 2016, a day before the month Billy was killed, data from the Philippine National Police (PNP) showed that at least 1,323 were already slain in police operations alone across the Philippines.

A month prior, in August 2016, the police identified at least 899 “deaths under investigation,” or what then-PNP chief and now Senator Ronald dela Rosa, the architect of the drug war, tagged as those gunned down by unidentified suspects or whose garbage bag-wrapped bodies were found in canals or streets.

“Bakit agad-agad ay nandoon na itong SOCO at punenarya? Kasi alam na nila ang mangyayari (The SOCO and the funeral parlors were already there immediately because they knew what was really about to happen),” Melanie said.

Agony with police

The responsibility to process papers related to Billy’s death fell on Melanie. But with it came visitations from authorities, scaring the already traumatized family. The first time the police visited, they looked for Billy, much to Melanie’s confusion. Her nephew was already buried, what more do they want? So she told them nonchalantly – with a bit of sarcasm – to go to the cemetery. Maybe they could talk to him there.

Police came knocking again a few months after. This time, however, they asked Melanie if the family wanted to file a case against Billy’s killer. They did not show any information about their investigation, nor proved they indeed did any prior investigation at all.

When Melanie declined, the police asked her to write something, saying that the family is not anymore interested in pursuing legal action.

“Tinanong ko sila para saan ito, ang sabi sa akin napag-utusan sila kasi gusto nila mahanap ang mga mamatay-tao,” Melanie said.

“Gusto ko sabihin na paano ‘nyo mabibigyan ng katarungan eh kasamahan ‘nyo ang mga pumatay sa aming mga mahal sa buhay, pero hindi ko nasabi sa kanila kasi siyempre takot din ako,” she added.

(I asked them why they’re doing this, and they replied that they were just acting upon orders because they wanted to catch the suspect. I wanted to tell them how they could give us justice when it’s their own colleagues who killed our loved ones. But of course I didn’t say that out aloud because I was also afraid.)

Melanie wrote and signed a waiver not because she did not want justice, but to avoid any trouble. She feared that the huge challenges that came with just obtaining an official report on Billy’s death would rear their ugly heads again.

There was an incident, in the middle of going back and forth with the police, when authorities asked Melanie to visit a station in the middle of the night. At one point, she was also told not to mention that her nephew was killed under Duterte’s drug war. Just say he was gunned down, one officer told Melanie. Stay quiet, he warned her.

“May nagsabi din sa akin mga isang taon pagkatapos ko nakuha ang mga papeles, kung para lang ba iyan sa benepisyo, baka raw magsampa naman ako ng kaso,” Melanie recalled. “Sabi ko, hindi, sinunog ko na lahat ang mga iyon, para lang tumigil sila.”

(A year after I got the documents, someone asked me if those were really just for claiming benefits, maybe I might use them to file cases. I said no, I burned everything already, just so they would stop.)

The issue with waivers

Police approaching victims to ask if they’re interested in filing cases is not an experience unique to Melanie. The Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights), a civil society organization that has documented the drug war, recorded at least 13 families who were in similar incidents over the years.

Only one family did not sign, while the rest did what the police told them to do. Rappler interviewed three families who signed the waiver and their reasons mirror the long-running issues faced by those left behind by victims of Duterte’s drug war. They are scared that they would be killed next if they dare go against those in power.

Rappler reached out to the Philippine National Police on April 28, 2023 to inquire if making families sign waivers is an agency-wide policy, but has yet to receive a response. We will update this story once we receive their reply.

Human rights lawyer Jin Arabejo, a project coordinator at the Alternative Law Groups (ALG), told Rappler that “legally, these waivers carry little to no weight.” Families who ultimately had no choice but to sign the waivers may still file legal cases in the future should they decide to do so.

He cited Article 6 of the Civil Code of the Philippines, which states that rights may be waived “unless the waiver is contrary to law, public order, public policy, morals, or good customs, or prejudicial to a third person with a right recognized by law.”

“The act of police officers asking families to sign a document stating that they are waiving their right to pursue legal cases against perpetrators puts the families under duress,” Arabejo explained.

He added that under Republic Act No. 7438, any person “arrested, detained, or under custodial investigation” shall at all times be assisted by a legal counsel. Waivers signed by families of drug war victims without the presence of counsel, according to Arabejo, “will be invalid.”

Police cannot force families to sign waivers in the first place. Arabejo emphasized that a valid waiver should have three essential elements, including the intention of a signatory to relinquish a right. Being forced to sign goes against having the intention to do so.

Families who face this specific issue are advised to do the following:

- Prioritize their safety first

- Seek assistance from a lawyer, a civil society organization, and/or from the Commission on Human Rights

- Make clear documentation by asking police their identifying information and why they are being asked to sign waivers

- Make sure that there are people nearby who can witness what is happening

In the event that there is already danger and if options are not immediately accessible, Arabejo said that families should just sign the waiver “and simply contest it in the future if the waivers are used against them.”

Blocking good fight in court

Families are not to blame for their decision not to pursue legal action against alleged killers of their loved ones. They have all the reasons to be afraid as many of them witnessed firsthand the killings. They know who the killers are – either the police or those who worked for the police – and acting on that information could mean harassment, or worse, death.

It didn’t help that the police already created a difficult environment following these killings in areas where they operate. Over the years, families of victims whom Rappler talked to reported strangers making their presence felt in their own communities, during wakes, or even burials of their loved ones. Many widows and their children were forced to live their own homes – sometimes temporarily, often for good – to evade danger.

Families also mentioned similar incidents where they were subjected to police intimidation once they took steps toward obtaining official reports, even if only to get social benefits that could ease the financial burden that came with losing a breadwinner. Police, they said, were wary that families would use documents for legal cases.

“[Families] can just imagine if they file a case, it would be a big headache on their part, not to mention the expense,” PhilRights executive director Nymia Pimentel-Simbulan told Rappler in an interview.

“They made it very difficult for families to be able to secure the necessary documents that would enable them to put up a good fight in court,” she added.

Even the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), the independent body mandated by the 1987 Philippine Constitution to investigate state abuses, have had a challenging time investigating these killings. In a report released in May 2022, the commission said their requests for documents were “oftentimes refused, denied, or ignored” by the PNP.

The difficulties of dealing with police mirror the bigger culture of impunity in the Philippines. There are only a small number of drug war-related convictions, including the policemen involved in the killing of 17-year-old Kian delos Santos and the deaths of Carl Angelo Arnaiz and Reynaldo “Kulot” de Guzman.

The number pales in comparison to the total death toll of Duterte’s drug war. Government data shows that at least 6,252 were killed in police operations alone by May 2022, while human rights groups estimate the number to reach between 27,000 to 30,000, to include victims of vigilante-style killings.

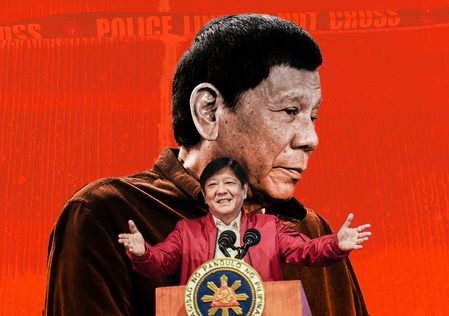

Killings continued under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., even as he made efforts to identify himself as different from the foul-mouthed president. Dahas, a project of the University of the Philippines Diliman’s Third World Studies Center, monitored at least 263 reported drug-related killings between July 1, 2022 and April 22, 2022. At least 175 occurred during the first six months of the new administration.

For PhilRights’ Simbulan, the fact that the Marcos administration is yet to acknowledge the role of Duterte in the bloody human rights crisis in the Philippines spells doom for any improvement in terms of domestic mechanisms.

“There’s an outright denial on the part of the state, that there were no extrajudicial killings perpetrated by stage agents and if there were killings, they say these were in the course of the performance of their duties,” she said.

“The lack of trust and confidence of the people on the part of law enforcement agents, that will persist especially if they have not stopped engaging in activities violative of people’s rights,” Simbulan stressed.

No way but the ICC

With odds against them in the Philippines, families have pinned their hopes on the International Criminal Court (ICC), an independent tribunal that tries individuals accused of gravest crimes, including crimes against humanity.

ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan is currently investigating Duterte’s war on drugs, after the court’s pre-trial chamber green-lit the resumption of the probe in January 2023. Another chamber in March 2023 allowed Khan’s office to continue his work as the court hears the appeal filed by the Philippine government.

Latest developments at the ICC came after years of communications being filed by various stakeholders, including human rights groups and families of victims.

But the families weren’t always this open to dealing with the international tribunal, according to Simbulan. It also took years of building confidence and trust, with the victims and their welfare at the center of efforts.

PhilRights is one of the human rights groups that documented drug war killings in a bid to counter the lack of transparency under Duterte. They also supported widows and orphans by offering various livelihood and psychosocial projects, as well as by conducting human rights information campaigns across the country.

Simbulan said that these days, it’s the families themselves who initiate conversations about the ICC. They are eagerly asking for developments about the Philippine situation.

“When we opened the possibility of being able to seek justice internationally, specifically through the ICC, they embraced the idea,” she said.

“That is actually a qualitative change, a big leap, from the families’ attitude and behavior early on during our interactions,” Simbulan added.

Various experts and long-time court observers cautioned against being too optimistic about the ICC. The international court, after all, has had its fair share of criticism, including the lengthy process where no positive outcome is guaranteed.

Then there is the issue of the Marcos administration’s firm stand against the ICC. The incumbent Philippine president is still allied with the Duterte family and his vice president, Sara Duterte, the former president’s daughter, continues to be at the center of an expansive network of loyal allies.

PhilRights’ Simbulan said she doubts Marcos will have the courage to run after Duterte. “Maghahanap at maghahanap ng possible na lusot iyan (He will always find a way out of it),” she said.

Recent ICC developments reflect this reality. Taking a leaf out of the Duterte playbook, the Marcos administration continues to falsely accuse the court of interfering with the country’s internal affairs, among others.

But for Melanie, the ICC is their only shot at justice. Why deprive thousands of drug war victims and their families of this when the country’s own justice system cannot do that?

“Ang intensiyon lang naman [ng ICC] ay bigyan kami ng pag-asa na maimbestigahan nang mabuti ang mga patayan, at ipaintindi sa gobyerno ang karapatang pantao kaya maganda na sana na hayaan na silang gawin ang dapat nilang gawin,” she said.

(The ICC’s only intention is to give us hope that the killings will be investigated fairly, and to let the government understand human rights. So it would be better if the government would just let the ICC do what it should do.) – Rappler.com

*Names have been changed for their protection

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Vantage Point] China’s silent invasion of the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-china-silent-invasion-july-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] A Duterte and Bato cop named Patay](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/tl-lito-patay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=322px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[In This Economy] Marcos’ POGO ban is popular, but will it work?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/thought-leaders-marcos-pogo-ban.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Rappler Investigates] POGOs no-go as Typhoon Carina exits](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/newsletter-graphics-carina-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=424px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[EDITORIAL] Sorry Arnie Teves, walang golf sa kulungan](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/animated-arnie-teves-arrest-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=310px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Vantage Point] The PDEA leaks](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/vantage-point-pdea-probe.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Edgewise] How Duterte can elude ICC arrest](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/thought-leaders-How-Duterte-elude-icc-arrest.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=272px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.