SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

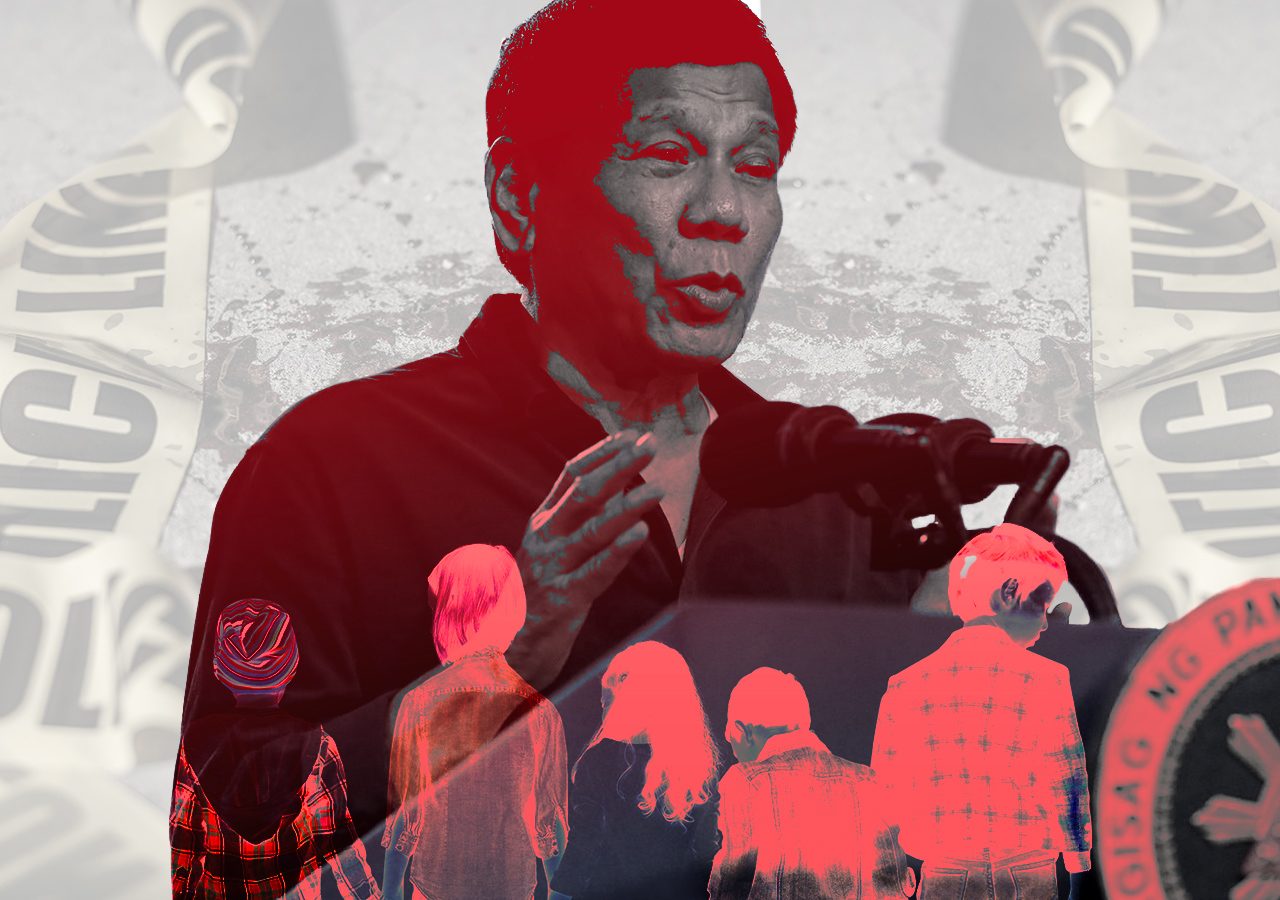

Editor’s Note: More than six months since Rodrigo Duterte stepped down from the presidency, thousands of orphaned children, wives, mothers, siblings, families left behind by victims of the violent war on drugs continue to relive painful memories. Coming mostly from the poorest communities across the Philippines, they pine for justice and accountability, some still pinning hopes on the International Criminal Court to investigate the killings. In this series, Rappler revisits some of those who were left behind – to listen and retell their stories – as they seek justice in the face of continuing fear and challenges post-Duterte.

Third of 4 parts

PART 1 | Drug war widow: Why is Duterte still free when our loved ones are dead?

PART 2 | Pain lingers as 2 brothers lost under Duterte’s drug war, 1 under Marcos

MANILA, Philippines – A small house with dilapidated wood for walls in a crowded Metro Manila district may not be the ideal place to raise five children, but Dina* tried her best to make it work, even if violence crept from many dark corners of Rodrigo Duterte’s Philippines.

Her husband had been in and out of jail for reasons that the family had long given up trying to understand. In their heart of hearts, they know he was a good father. But police thought he was a menace to society.

The family wanted to fight for her husband’s freedom, to question why it was so easy for authorities to lock him up, but Dina had five mouths to feed. She had five young people relying on her for survival, she couldn’t waste the days away waiting for her husband to come home.

For many hours daily, Dina scavenged through trash scattered along busy streets, blending in with other people who also strove to make ends meet. She pulled apart piles of discarded materials to look for things worth selling, to take home something for her children.

“Napakabait po ng nanay ko, pala-kaibigan at mapagbigay sa mga kapitbahay,” Jenny, Dina’s third child, told Rappler on Monday, January 30. “Wala siyang nakakaaway.”

(My mother was so kind, friendly and generous to our neighbors. She didn’t have an enemy.)

While the work didn’t really bring much money, at least it put food on the table. But Dina, her daughter said, always found ways on days that scavenging yielded nothing.

One night in 2016, she went out to make sure her family didn’t sleep on empty stomachs. Dina went to a friend’s house to ask for food, as she often did when times got tougher than usual. She had an empty bowl on one arm and her youngest child on the other.

It would be the last time her children – the eldest then only 19 years old, the rest not even in their teens – would see their mother alive. She would fall victim to the violence that thrived under the violent war on drugs.

Dina was shot dead by police during an anti-illegal drug operation, one of the people killed that night. She was just a few feet away from her friend’s house when policemen reportedly surrounded the area, leaving no place for the mother and child to elude the bullets. Then there were gunshots.

Her youngest child whom she was carrying at the time of her death was injured and had to be brought to the hospital.

Jenny could only recall the night with images imprinted on her 11-year-old mind back then. She remembered playing with her siblings and her mother walking out the door to find food. She remembered the hunger pangs that came with waiting, and then someone telling her the tragic news.

The family heard different versions of why their mother ended up being riddled with bullets when she was just supposed to find food for the family. There were people who said Dina was in the wrong place at the wrong time, as the police operation targeted a different person. There were also rumors that she was mistaken for a drug personality who shared the same name.

But for the children who were drowning in a sea of grief, one thing was clear: They had lost a mother.

“Ang kuya ko halos mamatay na sa kakaiyak habang ang ate ko naman hindi na alam ang gagawin niya,” Jenny, now 17 years old, recalled. “Hindi namin alam kung bakit nila pinatay ang nanay namin kasi wala naman siyang ginagawang masama,” Jenny continued.

(My eldest brother almost died crying while my sister didn’t know what to do. We didn’t know why the police killed my mother. She wasn’t doing anything bad.)

Losing mother’s guidance

Living in poverty has forced many children in the Philippines to grow up faster than most. In the aftermath of Dina’s untimely death, Jenny and her four siblings had no choice but to bravely face the world on their own.

Life was hard even before they lost their mother, yes, but they knew that Dina would always find a way to ease the burden on the family. It was Dina who made sure everything would be okay.

“Kahit mahirap ang buhay namin, basta importante magkakasama kami sa bahay na hinaharap iyong mga problema kasama si nanay (Even though life was hard, what was important was we were together at home, facing the problems with our mother),” she said.

Their father was in prison when their mother died, so the children had to find ways to fend for themselves. The older siblings took on odd jobs available in their area, while the younger ones looked after their small home. They all pooled together whatever money they could get their hands on, even spare change, as they strove to survive without parental supervision.

Jenny, who was then barely in her teenage years, started working to help augment the family’s daily budget. When luck was on her side, she’d get paid at least P150 ($2.75) for hours’ worth of work, but those days were few and far between. There were many days she’d go home with nothing.

When days were rough – and there were many days like this – the children would just ask for food from other people who took pity on them.

“Nahihirapan kami kasi sariling sikap na lang kami na itinaguyod ang isa’t isa,” Jenny said. “Nagtutulungan na lang kami para lamang po may makain.” (We were having difficulty because we were trying to support each other. We were just helping each other to have something to eat.)

The almost seven years following their mother’s death were tough for the family. Their father was released from prison, only to get arrested again soon after. The only other adult in their life was their aunt, whose presence was as fleeting as the joy and happiness in their lives since they lost their mother.

These days, Jenny lives at home with two of her younger siblings. She has taken the role of both breadwinner and homemaker, while her older brother and sister had gone on to live elsewhere. At 17, Jenny has had to make several difficult decisions regarding her and her siblings’ lives.

She’d sometimes imagine what life would be like if their mother Dina were still alive, or if their father was a free person. Maybe they’d have someone to turn to when they felt lost and confused.

“Hindi po namin matanggap na kami na lamang ang bubuhay sa sarili namin, napakahirap po na walang magulang kasi walang gumagabay,” she said. “Hirap po ako na dalhin itong responsibilidad sa edad ko na ito,” Jenny said.

(We cannot accept that we are the ones who have to raise ourselves. It’s difficult to be without parents because we have no one to guide us. I’m having a hard time carrying this much responsibility at my age.)

Lasting impact on children

Jenny and her siblings are not the only ones who lost loved ones in Duterte’s war on drugs, the flagship program of the previous administration that killed thousands of people from the poorest communities.

Government data showed that at least 6,252 individuals were killed by the police by May 2022, a month before Duterte left office. This number does not include those killed vigilante-style, which human rights groups estimate to be between 27,000 to 30,000.

The effect of the slaughter does not disappear when the bodies are buried, nor packed in crowded apartment-style boxes in public cemeteries. It does not go away when the last tears are shed, or when a final wail is released from pent-up agony and anger as funeral attendants close the coffin.

An investigation by the Philippine Human Rights Information Center in 2018 found that Duterte’s drug war pushed poor families deeper into poverty, as many of those killed were breadwinners with irregular income.

Human Rights Watch, in a 2022 report, meanwhile, detailed the “harmful consequences” on children left behind by drug war victims. There were reported drastic changes triggered by psychological distress, which can last well into adulthood.

Orphaned children, or even those left to be cared for by single parents, often had to drop out of school to work and support their remaining siblings. They were forced to abandon their dreams for the sake of daily survival. The lack of government support for those left behind aggravates their situation.

Ever since Jenny can remember, she had always wanted to be a teacher. She couldn’t answer when asked what subject she would want to teach, but the 17-year-old said she enjoyed Filipino classes because of the stories her teacher required them read.

That dream, however, has to wait indefinitely. Jenny, who’s several years behind in schooling, had to drop out due to family responsibilities and financial struggles that came after their mother’s death.

“May balak po akong bumalik sa school kasi gusto ko naman mag-aral talaga, pero kapag nakaipon na siguro,” she said. “Wala talaga kaming pambili ng gamit.” (I have plans to go back to school because I really want to study, but maybe when I’ve saved enough money. We really do not have money to buy necessities.)

She swears the goal is still alive despite the hardships. Jenny still daydreams of standing inside a brightly-decorated classroom, in front of students not much younger than her siblings. But at the center of her wish to be an educator is the desire to help her younger siblings, who haven’t had the chance to enter classrooms and become students. Maybe their ate (elder sister) could teach them a thing or two about reading and writing, even just inside their small wooden house.

“Gusto ko sila maturuan at matulungan kaya pangarap ko maging teacher,” she said. “Pero alam ko na mahihirapan ako na abutin iyon, kaya nagsusumikap na lamang ako.” (I want to teach and help them that’s why I want to be a teacher. But I know it would be difficult for me to realize that dream, that’s why I just try my best.)

Why our mother?

Confronting the police about what happened to their mother may have crossed the minds of Jenny and her siblings, but they never acted on these thoughts primarily out of fear. Jenny recalled an instance when their family was harassed by policemen. She said the scary cops were asking for money but they had nothing to give.

If things were different, if the alleged perpetrators didn’t know their home, Jenny would have dared fight them in court. But the climate of impunity demanded a whole lot more of courage, which she wasn’t sure she had enough of.

“Masakit pa rin po na walang hustisya kasi iyon lamang po ang hiling ko talaga, na magkaroon ng hustisya para sa nanay ko na pinatay nila,” she said. (The absence of justice still pains us because that’s my only wish, to give justice to my mother whom they killed.)

Jenny joins thousands of families left behind by drug war victims, all persistently hoping for accountability, specifically from Duterte who launched the campaign in 2016.

Proceedings at the International Criminal Court (ICC) are the only ray of hope many families see as domestic mechanisms continue to fail them in their quest for justice. The ICC pre-trial chamber recently authorized the resumption of the investigation into the drug war killings, finding no genuine investigations by the government.

The timetable for what will happen next remains unclear, including when ICC prosecutor Karim Khan could potentially request for the issuance of summons or warrants against perpetrators of the drug war killings.

But Duterte has said he will never allow foreigners to judge him. Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla – who vowed “real justice in real time” before the United Nations – said that the government will not cooperate with the ICC probe.

The child whom their mother Dina was carrying when she was killed by the police is now 10 years old. It’s almost the same age as Jenny when she was forced to grow older and wiser beyond her years.

Jenny said her youngest sibling, the one who was injured in the police operation, doesn’t ask a lot of questions about what happened to their mother – unlike her.

“Gusto ko lamang malaman na bakit ang dami-daming namatay dahil sa mga pinaggagawa ng pulis, pero bakit parang walang pakialam ang Presidente natin ngayon?” she said. “Ang dami nilang nagawang kasalanan pero walang hustisya,” Jenny added.

(I just want to know why they aren’t doing anything even if the police killed a lot of people. And why doesn’t the President seem to care? They kept on killing a lot but there’s still no justice.) – Rappler.com

PART 4 | Under Marcos, can Duterte be held accountable for drug war killings?

*Names have been changed for their protection

*$1=P54.46

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Vantage Point] China’s silent invasion of the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-china-silent-invasion-july-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] A Duterte and Bato cop named Patay](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/tl-lito-patay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=322px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.