SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

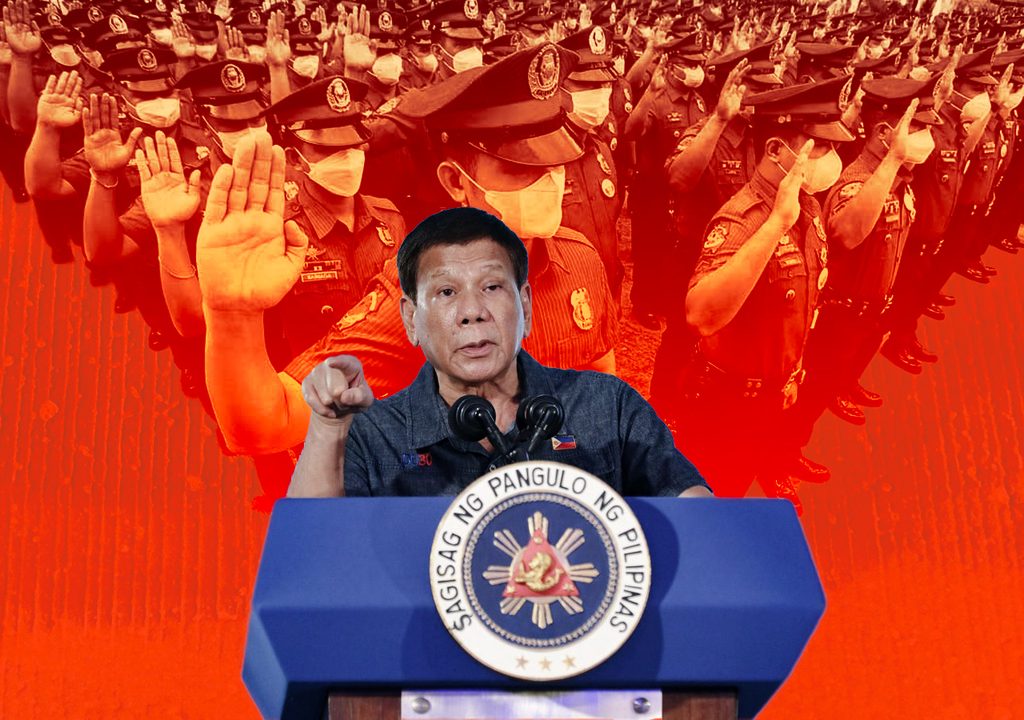

Editor’s Note: More than six months since Rodrigo Duterte stepped down from the presidency, thousands of orphaned children, wives, mothers, siblings, families left behind by victims of the violent war on drugs continue to relive painful memories. Coming mostly from the poorest communities across the Philippines, they pine for justice and accountability, some still pinning hopes on the International Criminal Court to investigate the killings. In this series, Rappler revisits some of those who were left behind – to listen and retell their stories – as they seek justice in the face of continuing fear and challenges post-Duterte.

Last of 4 parts

PART 1 | Drug war widow: Why is Duterte still free when our loved ones are dead?

PART 2 | Pain lingers as 2 brothers lost under Duterte’s drug war, 1 under Marcos

PART 3 | After losing mother to Duterte’s drug war, 17-year-old asks: Will justice ever come?

MANILA, Philippines – A widow left to raise three young children on her own. A family forever scarred by the pain of losing three siblings in less than six years. Five children forced to grow up beyond their years after their mother’s death.

Their stories may differ in various aspects like the method of killing, for example, but one thing they have in common is the intense desire of those who were left behind to obtain justice for their loved ones whose lives were brutally cut short by the violence that Rodrigo Duterte encouraged.

In their grief-stricken minds, the person who should face the courts is no less than the former president himself.

“Siya ang nagbigay ng kapangyarihan sa mga pulis na pumatay, pinangakuan na poprotektahan pa at bibigyan ng rewards kapag nakapatay sila,” Mila, whose three brothers were killed between 2017 and 2022, told Rappler.

“Siya dapat ang managot sa lahat ng ginawa niya sa mga Filipino, siya ang puno’t dulo nito,” she continued.

(Duterte gave the police the power to kill, promising them protection and rewards if they were able t kill. He should be held responsible for the things he did to Filipinos. He’s the root cause of everything.)

It’s no secret that Duterte was out to fight criminality by killing suspected drug personalities. It was central to his presidential campaign and it was widely accepted and embraced by many Filipinos.

Within his first year in office, at least 3,451 people were already killed at the hands of the police. This number would continue to grow as he marked each year in the presidency. By May 2022, a month before he left office, Duterte’s war on drugs saw at least 6,252 individuals killed in police operations alone, not including those killed vigilante-style which human rights groups estimate to be between 27,000 to 30,000.

Police narratives have always been the same – that the killings occurred because the suspects fought back. But these were proven false as independent bodies dove into the incidents, such as the Commission on Human Rights, which found “abuse of strength” and “intent to kill” by police in the cases they investigated. Even the panel created and led by the Department of Justice found in the records they examined that police did not follow protocols in anti-drug operations.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) recently authorized the resumption of an investigation into the killings under Duterte’s drug war, after being “not satisfied that the Philippines is undertaking relevant investigations that would warrant a deferral of the Court’s investigations on the basis of the complementarity principle.”

ICC Prosecutor Karim Khan is expected to gather more evidence that could potentially lead to a request for the issuance of summons or warrants. While it is still unclear who will be the subject of possible actions, the ICC is said to be usually interested in high-ranking officials.

The response of the Philippine government has been anything but welcoming, with the Department of Justice insisting that the country has a “working justice system” that can investigate the drug war killings.

But human rights groups and families of victims question this. In their eyes, the ICC is the only clear path to justice for their slain loved ones, especially if it is Duterte they want to hold accountable.

Can the justice system under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. even go after Duterte?

The Marcos-Duterte alliance

One of the biggest factors to consider when trying to gauge Marcos’ next move in relation to the ICC is the status of his alliance with the Duterte family.

Even before former Davao City mayor and presidential daughter Sara Duterte agreed to join Marcos’ ticket as his vice presidential bet in the 2022 national elections, there were already visible signs that showed how he and his family benefited from moves made by the Duterte patriarch.

These include the obliterated opposition Duterte left behind, as well as his decision to allow a hero’s burial for the late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos.

Political analyst Arjan Aguirre, a political science instructor at the Ateneo de Manila University, described the Marcos-Duterte alliance as “born out of convenience and pragmatism.”

“Just like any alliance that is based on political pragmatism, it is expected to be dissolved once the conditions, benefits, and gains for each party are perceived to be threatened or harmed,” he told Rappler.

Now that the elder Duterte has left office – ending his term as the most popular president post-Martial Law – it is his daughter Sara whom Marcos has to continue cultivating good relations with.

Her family name continues to command an expansive network of loyal allies within political clans and groups in the Philippines, aside from being the second-highest official in the land. Sara also garnered about half a million votes more than Marcos’ during the elections.

This means that while cooperating with the ICC is the ideal and right thing to do, Marcos cannot be expected to do anything that “would force Sara to bolt.”

“Allowing the ICC investigators to work with the Philippine government would definitely be perceived as a betrayal to the Duterte dynasty,” Aguirre explained.

“We can assume that this will trigger the dissolution of the coalition and will activate a series of attacks and offensives against the Marcoses from the Sara Duterte-[Gloria Macapagal] Arroyo bloc leading to the midterm elections of 2025,” he added.

Ignoring Duterte’s role

As it stands, there is no indication that the Marcos administration will make any move against former president Duterte in relation to the killings.

The most significant so far? Saying that the focus would be more on prevention and rehabilitation instead of law enforcement. In fact, Command Memorandum Circular No.16-2016, the document that laid out Duterte’s bloody drug war, is still in effect.

The government also recently asked police generals and colonels to submit courtesy resignations as part of efforts to cleanse police ranks of cops involved in illegal drugs. Interior Secretary Benhur Abalos said that only 12 out of the 955 generals and colonels did not follow the order.

Rachel Chhoa-Howard, researcher on the Philippines at Amnesty International, told Rappler that genuine accountability should include credible investigations and prosecutions. But they should also focus on senior police and politicians who may have had “direct and command level or superior responsibility for crimes under international law.”

“Under the principle of command responsibility for crimes under international law, responsibility should go all the way up the ladder for violations perpetrated in the ‘war on drugs’, and nobody should be automatically immune,” she explained.

“The normal legal rules should be applied, through civilian courts on the domestic level, and also through cooperation with international ones like the ICC,” Chhoa-Howard added.

Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights) executive director Nymia Pimentel-Simbulan said that cooperating with the ICC should be Marcos’ priority if he really wants genuine justice for the victims. Instead of openly attacking the court, the administration should just support the probe.

But the current pronouncements and positions of the government tend to show that the President has not learned from what happened under the Duterte administration. By dragging its feet and refusing to cooperate with the ICC, the Marcos government seems to be signaling its refusal to make Duterte responsible for the thousands of killings. And contrary to its declaration about prevention and rehabilitation taking precedence over law enforcement, it is indicating that violence is the “appropriate strategy” to take in the fight against illegal drugs.

Simbulan said this “will further embolden state and non-state agents, directly and indirectly involved in the drug war, since perpetrators of human rights violations will go scot-free and not be made accountable for their actions.”

Putting pressure on the government

The Philippines ceased to be a member-state of the ICC in 2019, a year after Duterte unilaterally withdrew membership from the Rome Statute following then-ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s decision to start a preliminary examination into the drug war.

But the country’s non-membership cannot be used as a shield against the ICC. Article 127 clearly states that: “[A state’s] withdrawal shall not affect any cooperation with the Court in connection with criminal investigations and proceedings in relation to which the withdrawing State had a duty to cooperate and which were commenced prior to the date on which the withdrawal became effective, nor shall it prejudice in any way the continued consideration of any matter which was already under consideration by the Court prior to the date on which the withdrawal became effective.”

Human rights and international law expert Ross Tugade said the provision is “clear that withdrawals from the Statute shall not affect the duty to cooperate,” emphasizing that the ICC retains jurisdiction over alleged crimes that occurred when the Philippines was still a member-state.

Yet the Marcos administration appears to have bent over backwards to protect Duterte and his minions against ICC scrutiny. Government officials have echoed similar messages heard during the Duterte era, when his allies would use weak justifications to evade accountability.

Their rhetoric invoked nationalism and supposed independence from foreign interference. For instance, Justice Secretary Jesus Crispin “Boying” Remulla on January 27 said the ICC is “insulting” the Philippines by pushing for an investigation, while presidential chief legal counsel Juan Ponce Enrile said he wants court personnel to be arrested if they enter the country as they “interfere so much with our internal affairs.”

Families and human rights groups are frustrated that their plight has gone unnoticed and their pleas unheard by Marcos while Duterte remains scot-free. These are on top of the challenges they face as they try to navigate the bureaucracy to obtain justice for their dead.

But can the Marcos administration be held liable for shielding Duterte and his drug war from the ICC?

Tugade, a lecturer at the University of the Philippines’ College of Law, pointed to a provision in the Rome Statute that covers offenses against administration of justice, but noted that it would be more applicable to individuals “actively and intentionally” obstructing the ICC processes.

According to Article 70 of the Rome Statute, the offenses against administration of justice “when committed intentionally” include the following:

- Giving false testimony when under an obligation.

- Presenting evidence that the party knows is false or forged.

- Corruptly influencing a witness, obstructing or interfering with the attendance or testimony of a witness, retaliating against a witness for giving testimony or destroying, tampering with or interfering with the collection of evidence.

- Impeding, intimidating or corruptly influencing an official of the Court for the purpose of forcing or persuading the official not to perform, or to perform improperly, his or her duties.

- Retaliating against an official of the Court on account of duties performed by that or another official.

- Soliciting or accepting a bribe as an official of the Court in connection with his or her official duties.

Successfully using these provisions against the government would be a long shot. At the end of the day, perhaps the most effective way to ensure smooth ICC proceedings – and to see Duterte finally face the court – is to actively call out the Marcos administration and remind it of its obligations to the victims.

“What comes to mind is putting pressure on the government to cooperate, this much we can do,” Tugade said.

“Seeing how the government is conducting itself throughout the investigation, it is expected that there will be a lot of resistance from their side,” she warned. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[WATCH] Bamban POGO scandal: There’s a bigger fish than Alice Guo](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/inside-track-tcard-bamban-pogo.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=435px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

![[Vantage Point] China’s silent invasion of the Philippines](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-china-silent-invasion-july-16-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=318px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[The Slingshot] A Duterte and Bato cop named Patay](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/tl-lito-patay.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=322px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Vantage Point] The PDEA leaks](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/vantage-point-pdea-probe.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=255px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Edgewise] How Duterte can elude ICC arrest](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/05/thought-leaders-How-Duterte-elude-icc-arrest.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=272px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[Just Saying] SONA 2024: Some disturbing points](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/TL-marcos-sona-points-july-23-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=335px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.